Anthropologists can find some redeeming value in creation myths when they see that they are condensed versions of cultural values. Sociologists from Weber to Durkheim have shown how certain elements of ancient western religion like the Torah and Jesus' revision of the Torah become structural elements of social codes, and so forth.

What do you make of Revelation? Here, there are no ideas. There's not a shred of socially redeeming ethical teaching, just fantastic visions of monsters, whores, angels battling demons. How do we account for the fact that ever since it was written, even today, the book has been enormously influential in western culture? (Although Jason Epstein, my editor, loves what I've been writing about it, he never misses a chance to take a swipe at the idiocy of people who actually read this book.)

I chose the book of Revelation as the toughest test case for the questions I've been asking myself. Why is religion still around, and not only among illiterates, exclusively, not at least? Why do people still engage in these folk tales and myths that are thousands of years old? And that's in their written form. Probably they were told for millions of years before that.

First thing I discovered is that controversy about this book is nothing new. Ever since it was written, Christians argued heatedly for and against it, when it barely squeezed into the Bible 300 years later. From the start, people who hated the book said a heretic wrote it. People who defended it claimed that it was written by one of the disciples of Jesus, which is obviously not the case.

I started with three questions. First, who wrote this book? And what was he thinking? Second, what other books of Revelation were written about the same time? How did this book, and only this one, get into the Bible? And what constitutes the appeal, whether you're talking psychologically, literarily, politically, of this book? So this is just a kind of mad dash through where those questions led me.

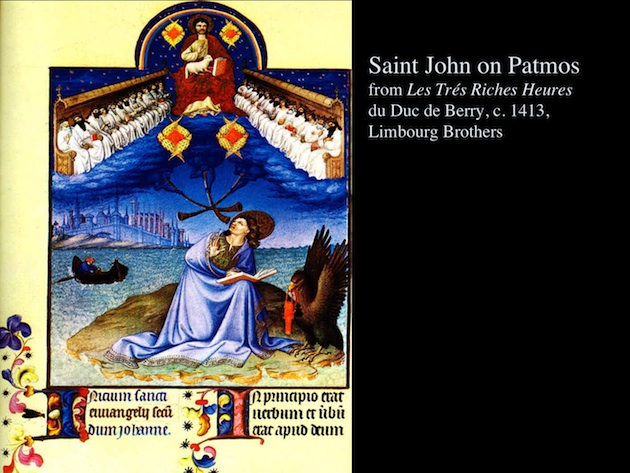

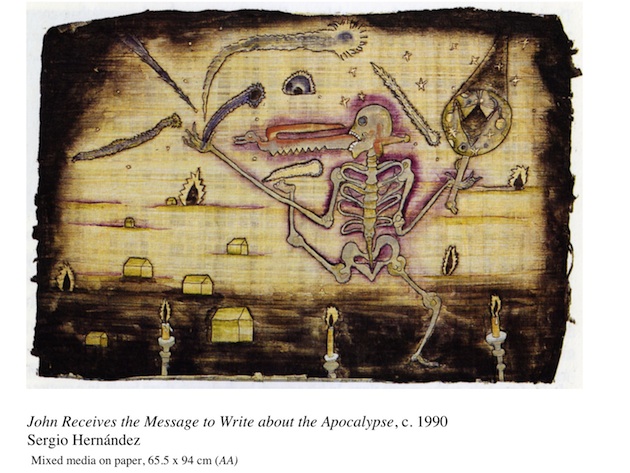

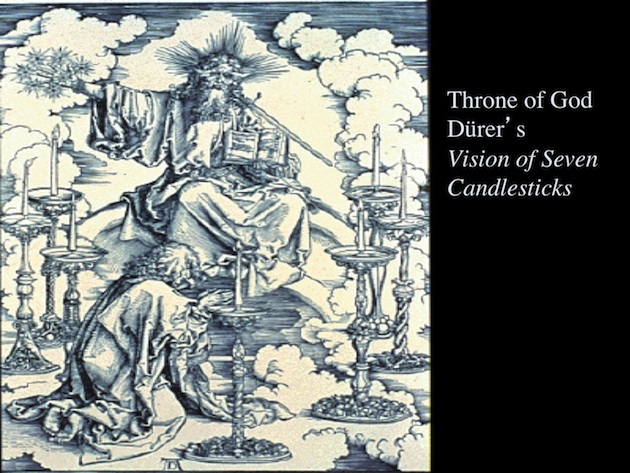

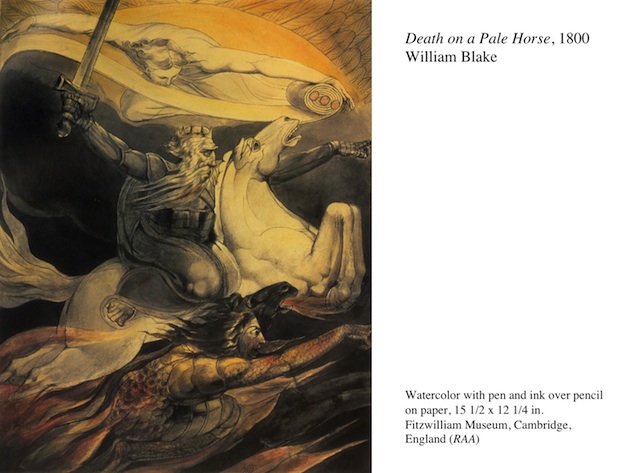

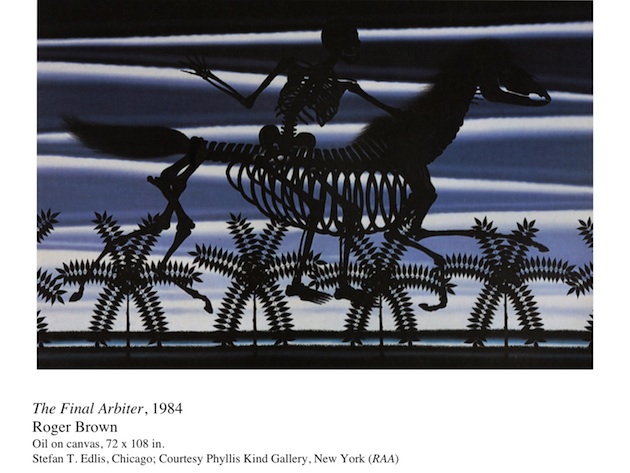

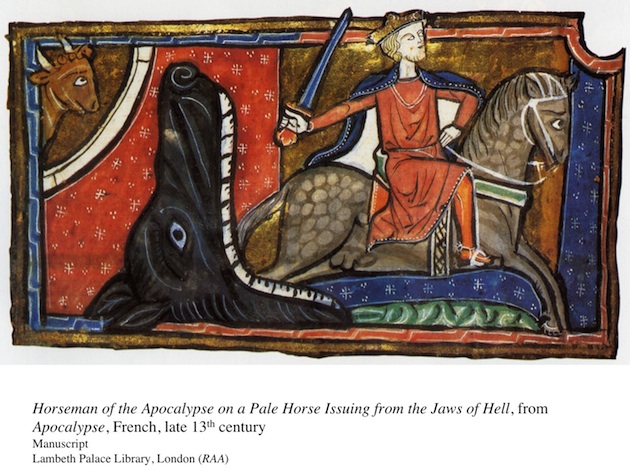

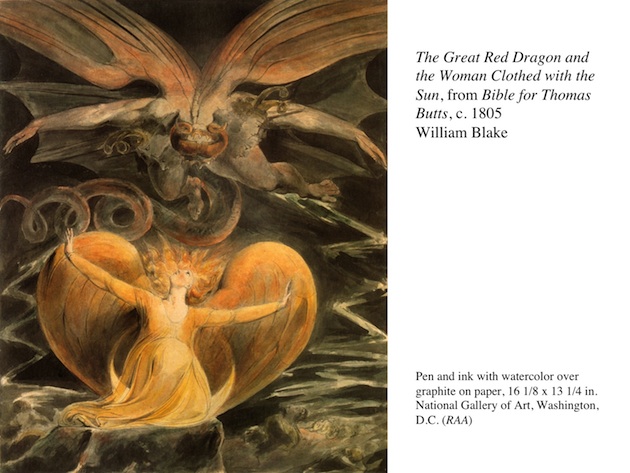

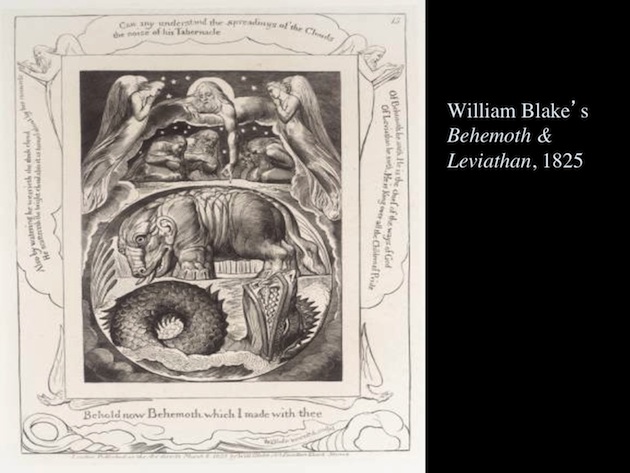

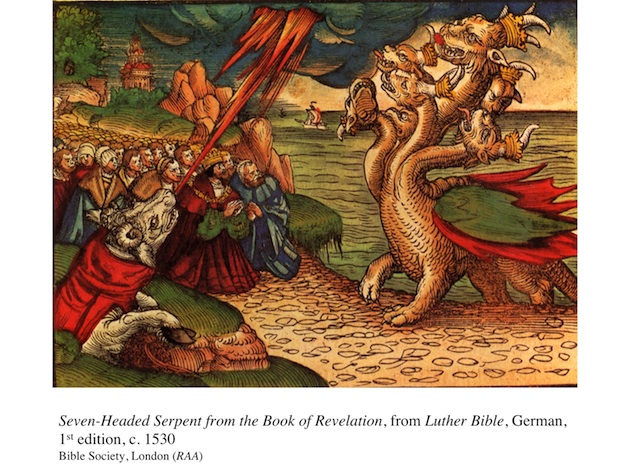

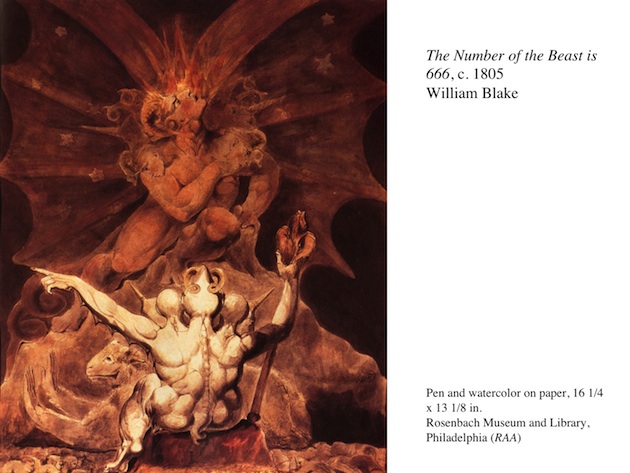

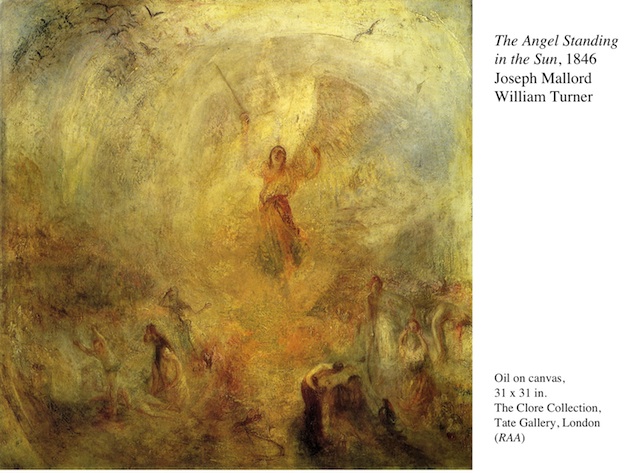

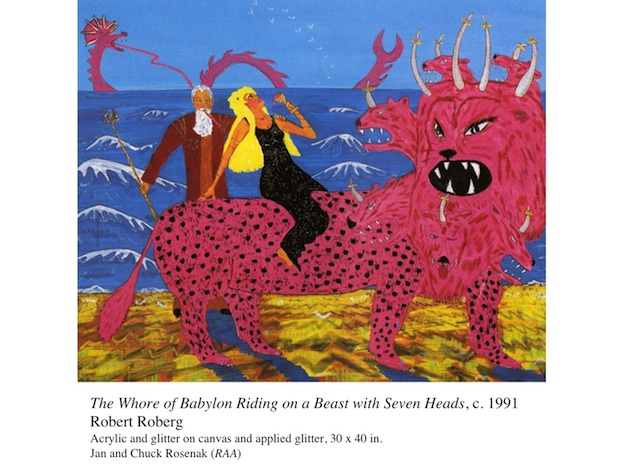

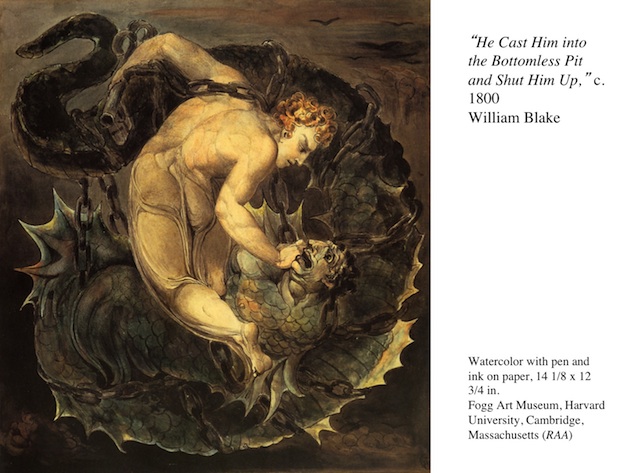

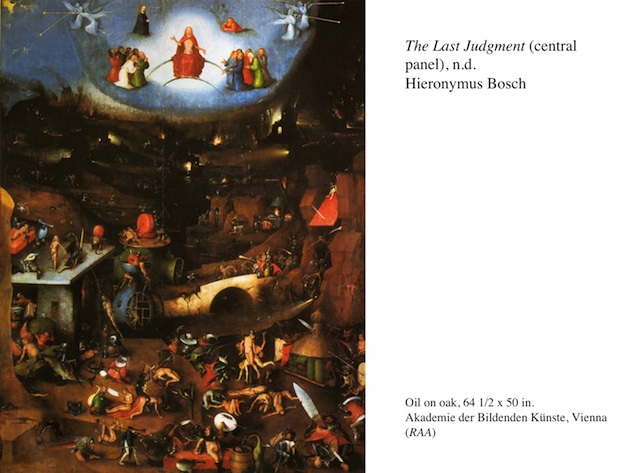

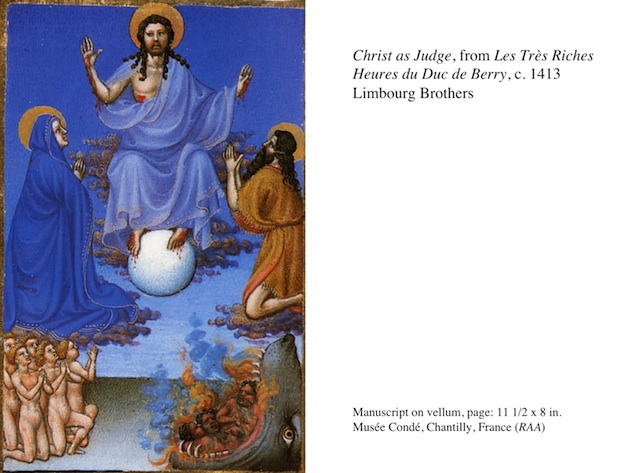

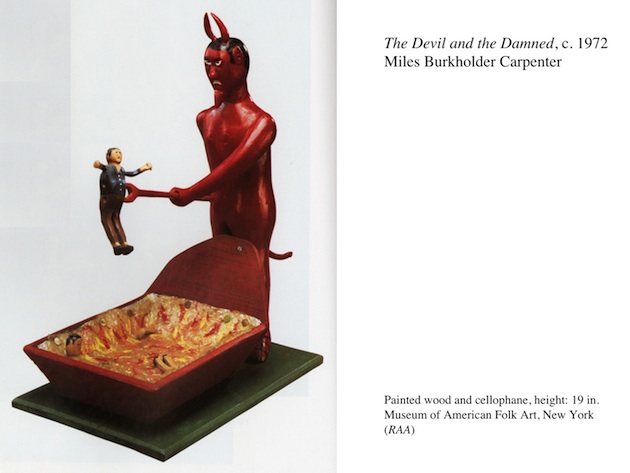

Now, just in case you haven't read it lately, I wanted to give you a kind of cliff notes version of the book's complex structure, along with some of the art it inspired, to show its cultural influence.

The author says he's a prophet named John. He claims to be a prophet called John of Patmos, because he said he wrote from the island of Patmos, which is about 50 miles off the coast of Turkey, in what was then Asia Minor. John said he was in the spirit, that is, he was in an ecstatic trance, when suddenly he heard a loud voice talking to him. He turned around and saw a divine being speaking to him, telling him what must happen soon.

John believed that the being who spoke to him was Jesus of Nazareth, but he wasn't in his human form. He was in a brilliant and angelic form that John believed the prophet Daniel had seen 600 years earlier, in a vision. John said that he looked up into the sky, and he heard a voice say, "Come up here." And he saw a door open in heaven. He went up into heaven, and he was able to see the throne of God.

What he was able to see was the throne of God, just as Ezekiel had described it about 600 years earlier in his prophecy, blazing with fire, lightning flashes, thunder bursts, gleaming like emeralds and rainbow sapphires light, and a sea of glittering crystal. John says it was like a dream, and next to the throne he saw a slaughtered lamb saying he was going to show what must take place after this.

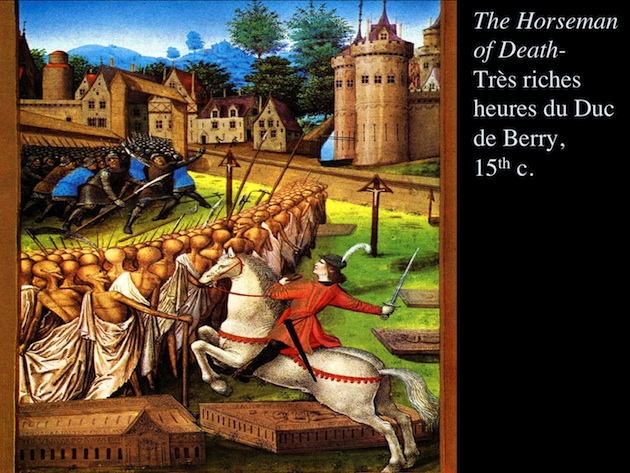

As angels sound trumpets, John said, the four horsemen of the apocalypse burst forth. The first one, riding on a white horse, wielding a sword;

the second one on a black horse, an omen of famine and inflation;

the third one on a fiery red horse, receives a sword for slaughter, so that people would slaughter one another.

And finally, the fourth rider, Death, brings violent catastrophe all over the world.

But before the action starts, John said he saw two signs up in heaven. He saw a woman, clothed with the sun, enormously pregnant, writhing in the agony of giving birth to a child, who was going to be the Messiah, and in front of her was a bright red dragon. Blake's dragon isn't that bright. But a bright red dragon stalking the woman, waiting to devour the child the moment that it was born.

The woman escapes, and the child is taken up into heaven. The dragon is furious, and storms off to destroy the children of the women on earth. The cosmic war is reaching its climax, and the dragon is now back on earth. The dragon has been thrown out of heaven. Here, you have the script by John Milton, kind of the staging by Spielberg, something like that. And the dragon is back on earth.

He calls forth two enormous allies. These are Leviathan and Behemoth, a male and female pair of monsters created in the beginning of time, as Blake pictures them. And he calls them forth as his allies. One of the beasts comes forth from the sea. He has seven heads and crowns on his heads, and he makes the earth and its inhabitants worship the beast. The second beast is bright red, and his number, John says, is a human number. The number is, of course, six hundred and sixty-six.

Next, John says, he was back in heaven, and suddenly he saw seven angels, each of seven angels carrying an enormous golden bowl. And each bowl is full of the wrath of God. And as angels sound the trumpets, the first angel starts to pour the wrath of God over the earth and catastrophes happen. This is actually the sixth angel, pictured by Joseph Turner, who pours the cup of God's wrath right over the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates River, where ancient Babylon was located.

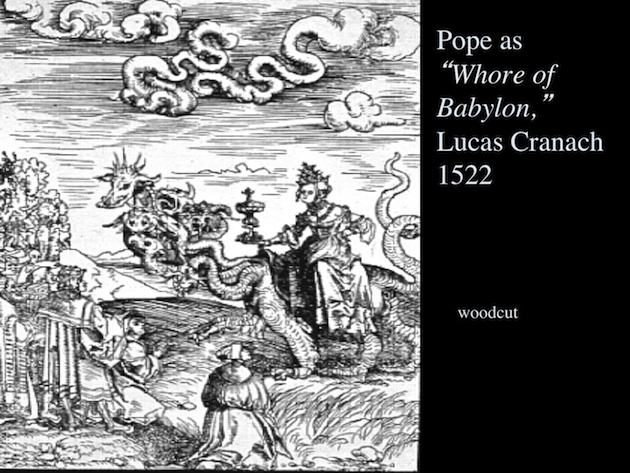

Finally, John pictures Babylon as the prophet Isaiah had seen Babylon. You may not recognize her, but she is a whore. She's sitting on a seven-headed red beast, and drinking from a golden cup, the blood of the saints.

Here's a contemporary version of the Whore of Babylon, drinking the blood of God's people.

Near the final act, Jesus comes forth from heaven on a white horse, like a divine warrior, leading all the armies of heaven to strike down the nation and kill all God's enemies, John says, to rule them with a rod of iron, tread the wine press of the fury of the wrath of God almighty. And at that point, an angel shouts, invites all the vultures to come to the great feast of God, which will happen after the battle. The feast will consist of a huge heap of corpses, the corpses of the flesh of captains, rulers, the mighty, the horses and the riders, all of them, small and great, which will have been killed in the battle.

At that point, the forces join in battle. All who fight against God are killed. Satan is thrown into a pit and chained for a thousand years. The dead come back to life and stand before the divine throne where Jesus acts as judge of the world and casts all evildoers down into a lake of fire to be tormented forever. You see, here's the options. And finally, invites God's people into the new Jerusalem, where Jesus will now serve as king of the world, and reign in triumph for a thousand years. That's the story.

You may be wondering, who was John, and why did he write this? The evidence suggests that John was a Jewish prophet. He was living in exile around the year 90 of the first century. We can't understand this book until we understand that it was written in war time, or shortly after war. John was a refugee, apparently, from the Jewish war that had destroyed his home country, Judea, started, as you may know, in year 66 when Jews rebelled against the Roman Empire. The slogan of the war was, "In the name of God and our common liberty." And four years later, in the year 70, 60,000 Roman troops stormed into Jerusalem and killed thousands of people. They said that the blood was as high as the horses' bridles in the city of Jerusalem. That's what Josephus wrote in his account of the war. And starved and raped, and killed thousands of people, and then finally attacked and burned down the great Temple of God which formed the entire city center.

John put his own cry of anguish in the mouth of people he said he saw standing under the throne of God. They were dead. They were standing there, the souls were crying out this cry: "Lord, how long? How long will it be before you judge and avenge our blood on the nations of the earth?"

Many other Jews were asking questions like that. But John wasn't quite a traditional Jew, since he had joined the sect devoted to Jesus of Nazareth. John had somehow been convinced that this Jesus was not only during his lifetime, but still … and this is 50 years after his death … still is God's appointed future King of Israel, in fact, the king of the whole world.

Other Jews thought that Jesus' followers were crazy, of course, because by this time he'd been dead for 60 years, as you know tortured and killed by the Romans as an example of how imperial rulers dealt with treason. The Romans regarded Jesus as one of the Jewish militants who incited the rebellion against the empire. They'd heard that Jesus had publicly announced that the kingdom of God is coming soon. And he'd privately told his followers that when the kingdom of God came, he would be the ruler in that new age, and rule as king over Israel, and in fact, over the whole world.

John is writing, amazingly, 60 years after Jesus' is dead. And after Jesus died, and after his leading followers were killed, his brother James had been lynched in Jerusalem by a mob; Paul had been beheaded; and Peter was crucified by Roman magistrates — most of the people who had joined this movement, of course, quit. But the John who wrote this book wasn't one of his original followers. He'd probably never met Jesus. He was a member of the next generation, but he was one of the dogged believers, convinced, in spite of all this, that Jesus had been right when he said that the kingdom of God was coming soon, and he privately told his followers, as I said, that he was going to rule as king over Israel.

John was convinced that Jesus who had been killed and tortured and executed by the Romans had come back to life, was now ruling in heaven, and was preparing to come back to earth to return with power and destroy the evil powers that now rule the earth, the Romans being their latest incarnation. If you said to him, "How could you possibly believe all this?" John would have said he'd seen proof that the most incredible of Jesus' prophecies had already come true. He dared hope that the others would come true as well.

The earliest account we have is the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament. It says that a few days before the arrest of Jesus, he'd warned his followers that before the kingdom of God comes, terrible things would happen. There would be earthquakes. There would be conflict. There would be war. And finally, the unthinkable: enemy armies would surround and besiege Jerusalem, destroy and desecrate the great temple.

The Gospel of Mark tells how, when Jesus walked through the great temple, his followers were awed by its enormity, and its beauty. And he said to them, "You see these great buildings? Not one stone will be left on another." And he said all of this would happen within a generation. I tell you, this generation will not die before the kingdom of God comes with power.

You can imagine how John felt when, just a generation after that, a generation after Jesus' death, this shocking prophecy turned out to be true. The Romans stormed and destroyed Jerusalem and reduced the city center to rubble. When that happened, John and other Jews loyal to Jesus, horrified as they must have been, were very excited, because they thought, well, that happened, now, the rest has got to happen, too. John, and others, who were still the followers in this movement, began to write -the gospel is now in the New Testament — to spread the message of Jesus, and warn the rest of the world before the world would come to an end.

John fled Judea and expectantly waited for Jesus to come and take power. But by the time he began to write this book, another 15 years had passed. And then 20 years had passed. And 30 years had passed. Now, two generations had come and gone, and John, along with the rest, must have thought "What happened to the prophecy?"

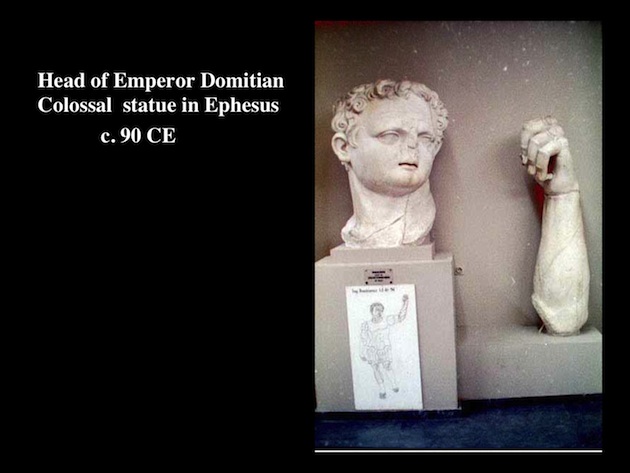

When John travelled through the provinces of the Roman Empire, particularly in the province called Asia Minor, which is now Turkey and Syria, John would have seen that every evidence that the kingdom that had come with power wasn't God's kingdom. It was Rome. When he approached the gates of Ephesus, the greatest port in Asia, and walked on the great road that leads into the city of Ephesus -I'm sure some of you have been there — he would have seen the magnificent temples and the monumental city buildings crowded with statues of emperors and gods, and probably could have seen on that great road the statue of the ruling emperor, Domitian, a colossal statue. Domitian's father, Vespasian, his brother Titus, had been the military commanders who had ordered the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple.

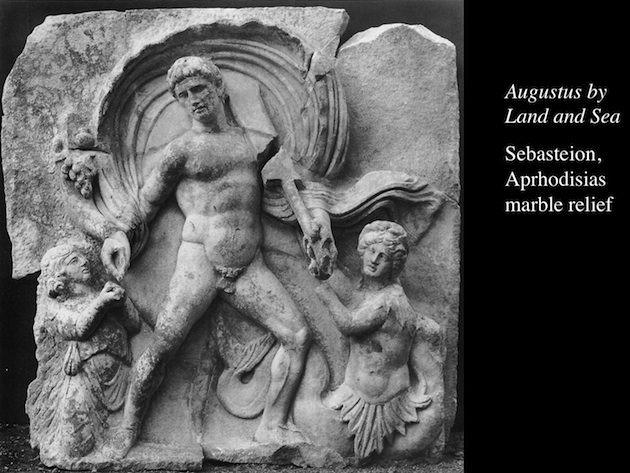

John would have seen huge temples in Ephesus built as part of a propaganda campaign that was started by Augustus, at the beginning of the first century. Augustus created enormous building campaigns to glorify his imperial dynasty, temples like one in Rome called the Sebastian, which means the Temple of the Holy Ones, and there were many copies of the Sebastian, you could see this one near Ephesus.

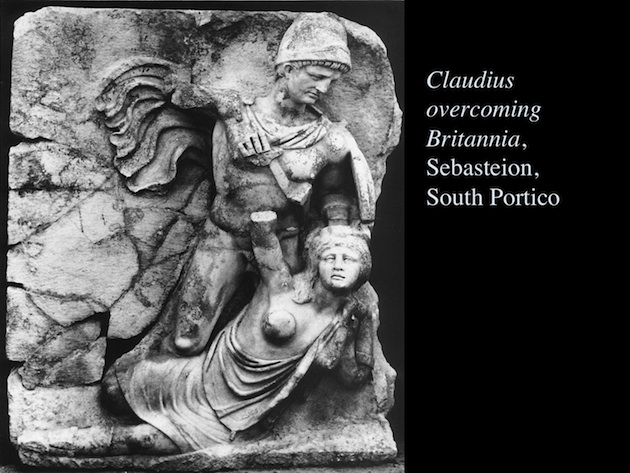

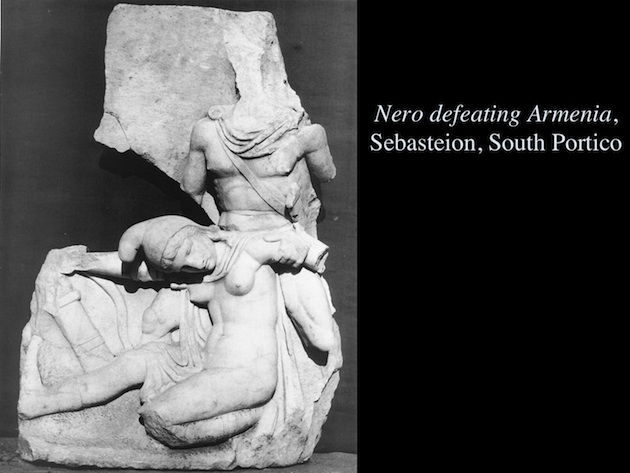

As John walked around, any traveler would walk around, 30 enormous panels on this vast temple, he could see Augustus ruling land and sea, as the centerpiece of this great temple, and then most travelers would have been very impressed by the vision of Rome's conquest over the entire world, because every panel would show you an emperor, naked, to show that he is like a god, but with military weapons, subduing, killing, tormenting a female slave, who represents one of the captive nations.

This is Claudius subduing Britain. And he's lifting his sword to cut her throat as she wields her arm to try to ward off the death blow, but it's completely in vain, as you can see.

The next panel would show Nero defeating the slave Armenia, and forcing her to the ground. Now, this is a very impressive display of Rome's power. But John, of course, belonged to one of those captive nations, Judea. And I think John would have had a very different reaction. Instead of being impressed, he would have been extremely angry.

John says it was while he was in that area, right near Ephesus, that he first heard a divine voice, and had a terrifying vision in which Jesus said that Israel's God is about to come and destroy the evil powers of the world once and for all. What John did in the Book of Revelation was draw on the cultural resources of his own people to create, if you like, anti-Roman propaganda. Especially, he drew on the writings of the classical prophets like Ezekiel and Daniel, Isaiah, because those prophets writing hundreds of years before John — he was immersed in their writings — had written many of them about 600 years earlier, about the time that Babylonian armies had destroyed and devastated the nation of Judea and the city of Jerusalem.

What the prophets did is, they took the most ancient version of the creation story — it's not the one you find in Genesis. The most ancient creation story tells how the God of Israel had to fight a giant dragon. This is a Babylonian story. It goes back to the god Marduk. But they took the story about God fighting a dragon in the beginning of time, and they applied it to the crisis of the war. The prophet Jeremiah talked about how the king of Babylon is a beastly sea monster whom God spears and slaughters. The prophet Isaiah calls on God to wake up and fight against Israel's foreign enemies. Isaiah pictures Israel's enemies. It's the Babylonian empire. He says, "That old serpent, the dragon, Leviathan, the dragon that lives in the sea." Isaiah also pictured Israel's foreign enemies as a rich and decadent whore.

When John of Patmos, who was steeped in these writings, asks, "How long is God going to allow evildoers to triumph over Israel?" he says Jesus told him what the earlier prophets had said, that God is about to come and finish the cosmic war he started in the beginning of time, and kill the dragon who embodies the forces of evil once and for all. John of Patmos triumphantly says that today's Babylon, which is Rome, although it's raging like Leviathan, is decadent as the whore, is about to fall as Rome triumphs.

Just a note that this Book of Revelation doesn't contain things that many of its contemporary admirers claim to find. It doesn't have anything about a rapture. It doesn't have anything about a requirement that Jews become Christian. Although, for over a thousand five hundred years, John's book has been in the New Testament, John had no anticipation of a New Testament, because his only scriptures were the Hebrew Bible. John regarded himself as a Jew who had found the Messiah. And would have been shocked to learn that his future readers regarded him as a Christian. As far as he was concerned, Christianity hadn't yet been invented. John never uses the term Christian. He wouldn't have applied it to himself, even if he knew the term. We don't know if he knew it, because it was probably coined by Roman soldiers to identify gentiles, that is, non-Jews, accused of atheism, because they didn't worship the gods of Rome, and accused of treason because they were now devoted to a cult that followed the seditionist, Jesus of Nazareth.

At the same time, while John was visiting small groups of Jesus' followers in Asia Minor, 20 to 30 years after the Jewish war, he was distressed to learn that there were followers of the apostle Paul who were teaching a kind of quick and easy teaching about Jesus that John felt was all wrong. John was preaching that the cosmic war that the prophets predicted was about to envelop the world, and you better get ready for Jesus to return in power, and John warned that belonging to Israel was a privilege that required Jews to be holy, particularly in matters of diet and sex.

But Paul, who had lived about a generation earlier, like John, he'd never met Jesus, actually. He only said that after Jesus was dead, he had had visions of Jesus and Jesus had told him a message to give to gentiles. And this message was a very different message than John's teaching, and it was meant for a very different audience.

Paul said he'd been taught to preach to gentiles. And he was supposed to teach that Jesus had died for the sins of the whole world so that now anyone, Syrian, Greeks, Africans, Spaniards, Gauls, whoever it was, who simply believes in the good news about Jesus, could skip all kosher requirements, and share in Israel's blessings. All you had to do was be baptized in the name of Jesus.

Paul not only encouraged his gentile converts to see themselves as becoming members of Israel, but he actually said in some of his letters to his converts in Greece and Turkey, that they could become the real Israel, the spiritual Israel, and he said, not like my kinsmen according to the flesh, that is, other people born Jews. He said, in a way, they're not really the true Israel any more. They're just the Israel according to the flesh. And they fail to understand that their own scriptures are all about Jesus.

Although John was traveling in Asia some 20 years after Paul died, he met there many second generation followers of Paul who were spreading the apostle's teaching all over Syria, Greece and Turkey. And teaching, they went further than Paul. They were saying, these gentiles were saying they were actually the true Jews, because Jesus had actually disinherited his chosen people.

That kind of teaching made Paul angry. And so he said, I don't care if these converted gentiles say they are Jews, he said, they're not. They're lying. Instead of belonging to Israel, they belong to Satan's synagogue. John could not have imagined what he would have regarded as the greatest identity theft of all time, that eventually gentile believers would not only call themselves Israel, but claim to be the sole rightful heirs of Israel's legacy.

In retrospect, we can see that he stood on the cusp of an enormous change. This movement, which attracted few Jews within two to three generations after the death of Jesus, was attracting floods of gentiles all over the empire, particularly in those other provinces. And these other people would flood the movement and create, in effect, a new religion. We now know that John would have been distressed to know that leaders of this movement would posthumously adopt him as a Christian himself, and put his book in what they then called the New Testament.

But we now know that John's Book of Revelation wasn't, by any means, the only book of revelation written at the time. There was actually an outpouring of books of revelation at the time. They were written by Jews. They were written by Greeks, Egyptians, Christians. I have just a few of them in a kind of sample of hors d'oeuvres here. Many books of revelation, The Revelation of Ezra. The Revelation of Peter, and The Revelation of Paul, and The Revelation of Zostrianos and almost anyone you can mention.

Most of the other revelations, and this fascinated me, many of them were found with the Gnostic gospels in Upper Egypt, and they had been censored by church leaders for over a thousand and a half years. I'm fascinated by why those revelations are censored.

I just want to say a couple things about them. They vary a lot. There's an enormous range of other books of revelation. But first of all, they're not about the end of the world. They're about how you find the divine in the world now. Second, they give a very different picture of the human race. It's much more what Steve called an expanded circle, or Peter Singer did, right? An expanded circle that includes all species of animals, but not only animals, but also stars, rocks, cosmic entities like the sun and the moon and so forth. Christian leaders, as we'll see, rejected those as heresy.

But that just takes us to the third question, as I conclude, what made this book so appealing, and for whom, that it was included in the New Testament and proved so influential? I mentioned this book was very controversial when John wrote it. And it's not surprising that the people who championed this book during the next hundred to 200 years were followers of Jesus who were experiencing or witnessing Roman persecution first hand. They were living under threat of being arrested, tortured, executed, for atheism and treason. During those dangerous times, many of them found in John's prophecy hope that Rome, which was of course indomitable, was going to just fall and collapse at the end of the world. The Book of Revelation, as you see, talks about the world turned upside down. Suddenly the crucified, tortured, dead Jesus will come back and be king of the world.

What happened, though, is not what John prophesied. What came to an end wasn't the world. What came to an end was persecution. And it was astonishing. As you know in the year 312, on the night of October 12th, Constantine, who was the illegitimate son of an emperor, was preparing to fight his rivals, for the throne, and he said he saw a great sign in the sky that promised him victory in Christ's name. Constantine had that sign put on some of the weapons, and on the shields, had it carried before the armies into battle. And the next day he won a magnificent victory. His enemies were all killed. And he marched into Rome in triumph, and was acclaimed as emperor.

After this astonishing reversal, when Emperor Constantine shifted the Roman world toward Christianization, you might have expected that this book would get left in the dust, with other books of disproved prophecy. Many of them did. Over several decades, after Constantine and his successors became the patrons of the Christian Bishops, a lot of Christian leaders began to draw up a list, a canon, of authorized books. Canon means a standard. It's a measure you hold up to see what's a standard. And many of them drew up lists of books.

What's interesting to me is that, well, the earliest account we have is by a friend and counselor of Constantine, Eusebius, Bishop of Palestine, Caesarea, and he says in a very early account, well, he has a list of the recognized books. And he says, and if it's right, if it seems right to you, well, The Book of Revelation, we could add to that. Then he has a list of disputed books, and then it puts at the end of the disputed books, none of which are now in the New Testament. Well, if it seems right, maybe The Book of Revelation; because it's one of the most disputed books. We don't know. It's very highly disputed.

We have only five lists that remain from the year 350 to the year 400 of canon books, and you can see that the Bishop of Jerusalem, the Counsel of Bishops in Asia Minor, Gregory of Nazianus, this one's the Fathers of the Church and other bishops, they all have many books that are now in the New Testament. But every single list leaves out The Book of Revelation very deliberately, except the one list that happened to be the list that was adopted. And that book is included on Athanasius' list, the Bishop of Alexandria, in Egypt.

I was asking myself, what made Athanasius' take on Revelation different? Was it that he could actually reinterpret all the prophecies. Instead of taking John's prophecies as referring to God's victory over evil powers embodied in Rome, he said, well, you can't take it literally. We're going to apply John's vision of cosmic war to my lifelong battle, which is a lifelong battle to establish a Catholic church which is a Catholic church endorsed by the Roman Empire. This will become the church of what later becomes the Holy Roman Empire.

Athanasius was trying to create a Christian communion, which was supposedly universal Catholic, and he insisted that the war between the forces of good and the forces of evil is not against Rome, but it's against deviance and Christians who oppose the new Catholic church, either Pagans, later against Jews, and also against those he called maniacs and heretics.

Athanasius says, well, the beast is really not about Rome. The whore is not about Rome. The beast and the whore represent heresy. And when Jesus divides the saved from the damned, it's really the Orthodox Christians being divided from Pagans, Jews and heretics. And that is the way he pictures it throughout all of his writing. I mention this only because his spin on these prophecies shows us, gives a clue about how this book has survived for a couple thousand years.

One literary scholar says, well, these are very open symbols that John has, and another scholar at Yale says they're multivalent. It's very clear that John had very specific targets in mind when he was writing. For example, if you read about a great mountain that suddenly erupts, and is thrown into the sea and pollutes the waters for days, he's thinking about the eruption of Mount Vesuvius that happened in the year 79, about ten years before his writing. And everybody would know that. And if he's writing about the great beast whose human number is six hundred and sixty-six, you know that he's either thinking about the imperial name of the emperor Nero, who was the one you'd choose for the worst possible emperor, or Domitian, who was ruling at the time John wrote. He had very specific targets in mind.

I always think of Marianne Moore, the poet, who says, "Poetry is imaginary gardens with real toads in them." John knew what the real toads were. But the gardens were imaginary. And because he puts these images, he couches his meaning in images that could be easily deciphered by his contemporaries, but also hidden, because it was dangerous to attack Rome directly. In this kind of dreamlike image, those images, as you know, have been plugged in to almost any conflict ever since. They speak less to the head than to the heart, and to very intense emotions that shape our dreams.

I want to conclude by giving a sort of mad dash through some of the ways this book has played out.

This is painted during the time of the black death in Europe where about a third of the population died. And many people … this is the court painter of the Duke of Berry, who saw the black death as the emergence of the first horseman of the Apocalypse coming forth. Shortly after, when Martin Luther split the Roman Catholic church, his friend, Lucas Cranach, the artist, did wood cuts for the Luther Bible that is still published in the earliest edition of the Luther Bible, picturing in the Revelation section, the Pope as the Whore of Babylon, seated on a great, seven-headed dragon.

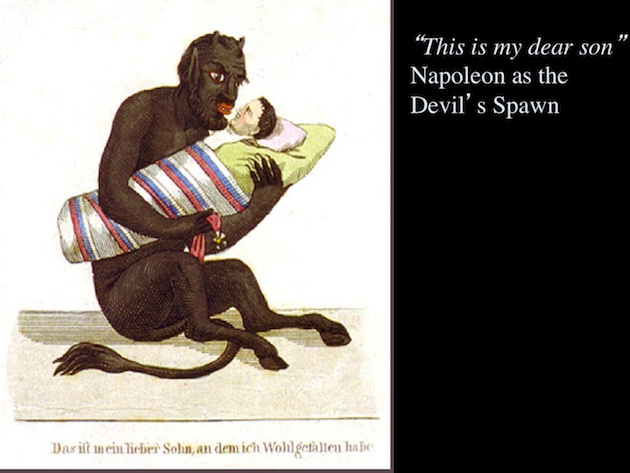

Luther's first biographer was a Catholic polemicist who pictured … this is the front piece of the Catholic biography of Luther, picturing Luther as the seven-headed dragon. Shortly after that, in the Napoleonic wars, Napoleon was seen by some as the son of the devil. These are just a quick run through.

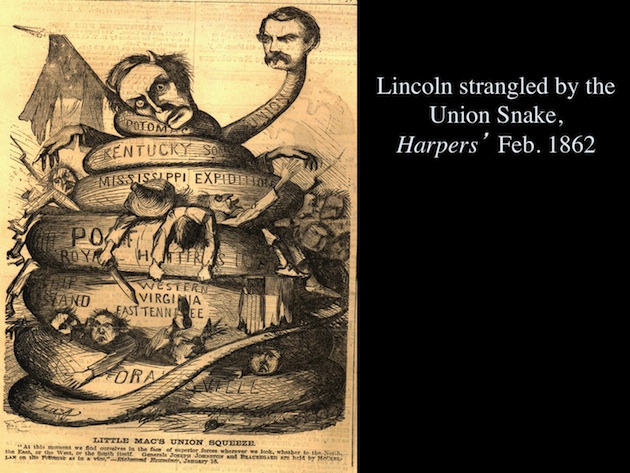

This is during the Civil War. This is a southern picture of the catastrophe of the Civil War. Lincoln is being strangled by the union, which is a great dragon, and a snake. And the southern confederacy took this battle of Armageddon as evidence that the end of the world was coming in that crisis. And of course, as you know, the north also adopted the same imagery. Julia Ward Howe, in his famous "Battle Hymn of the Republic", chose the imagery of The Book of Revelation to picture what was happening in that terrible war. I don't have to tell you, but … trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored … so forth. We don't have to go through all those. But you get the point.

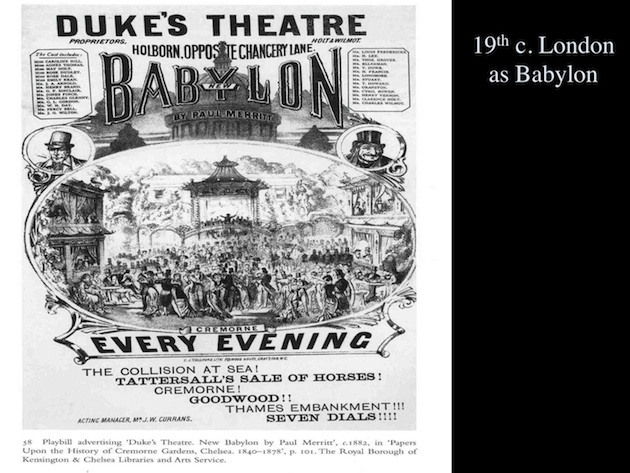

You know that Hobbs saw contemporary society in the 19th century, in his time, as a Leviathan, and this is a picture of London as Babylon, because of its vast corruption. You can see that people don't have to take Revelation literally to take it seriously, as an interpretation of good and evil. And just to show how labile those images have been, I've just recently read an interesting book called "The Holy Reich," which shows how some of Hitler's cabinet saw the Dritte Reich as the third kingdom, as the thousand year reign of Christ, which Adolf Hitler was thought by some to initiate.

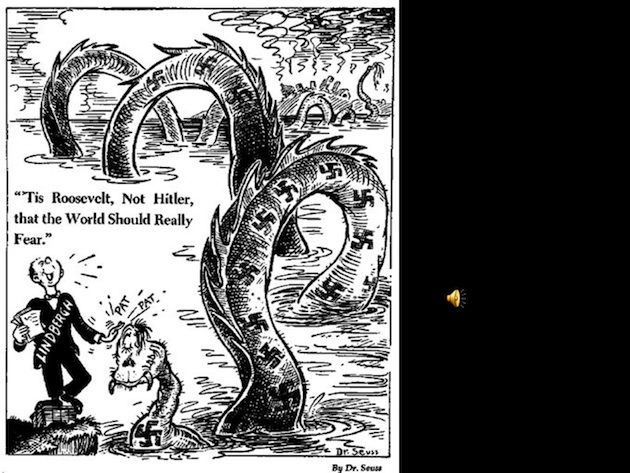

This is Dr. Seuss. Political cartoon picturing Hitler instead, of course, as the great dragon. And I just recall for you this music. I don't know if any of you know this music. This is written by Olivier Messiaen, who was a French prisoner in a Nazi camp. It's called "The Quartet for the End of Time". And Messiaen said he went out of the camp one day and he saw a rainbow in the sky, and the rainbow reminded him of the angel who appears in the 13th chapter of The Book of Revelation with one foot on the land and one foot on the sea, and the angel says, "There shall be no more time." And Messiaen wrote this "Quartet for The End of Time", which was played in 1944 on a freezing January night by prisoners for the guards and the prisoners of that camp for the first time.

You may recall the operation over Baghdad? You remember the name of it. Shock to the unbelievers, awe to those who believe. You remember that the angel, the sixth angel pours the cup of God's wrath right where the Tigris and Euphrates River meet. And some people understood that operation with the lightning and the thunder and the bombs over Baghdad as the fulfillment of the prophecy, delivered by American bombs.

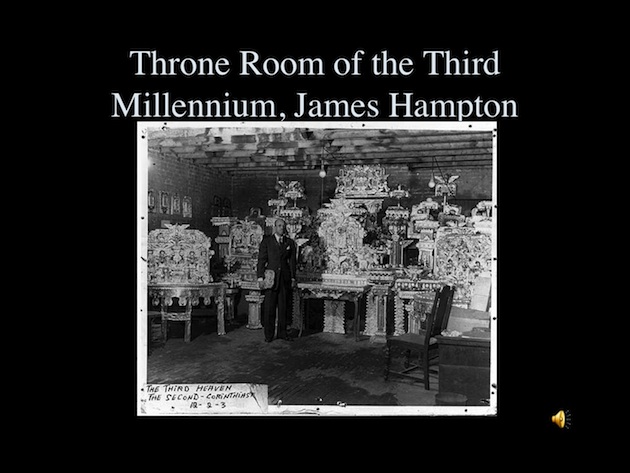

Finally, this is a piece of art that I saw in the Guggenheim Museum. "The Throne Room of the Third Millennium ". This was a piece of an enormous sculpture done in cardboard and aluminum foil, by James Hampton, who called himself the Director of Special Projects for the Third Millennium." And this is Blind Lemon Jefferson singing "John the Revelator," because this music is very important and powerful in that tradition.

I just give those as some examples of how those images work.

Q & A

STEWART BRAND: So why does religion still persist?

ELAINE PAGELS: I think because this is about emotion. This isn't conceptual. People who talk about it as if it matters whether you believe in God or not, have got it completely wrong. It's far too over intellectualized. This is about hope and fear. This is about how we dream. And I think it's because those images, the monsters, the whores, the beasts, it's about what we fear, what we hope. It's about revenge. It's about anger. We've heard about that. And it's still works, for some people.

JARON LANIER: When you read various ancient literatures, there's a striking difference in some of the western stuff, in that Jewish idea of a Messiah is an example of the thought that the future will be different and better from the past. It's not just prophecy to say who will have a child, or who will be King, but boosterism at a grand scale: The future will be different. This strange large-scale optimistic soothsaying was perhaps the first notion of progress, which preceded the enlightenment by a long time, but was a seed as it turned into the enlightenment eventually.

ELAINE PAGELS: There are a lot of people who will find in this moral meaning. The idea that the world, we see all these chaotic and horrible events happening here, plague, and war and catastrophe, and earthquakes, and tsunamis. But somehow it all has a coherent order somewhere, somewhere there is meaning. I think it's about meaning, too. John doesn't ever tell you what the meaning is. But he certainly gives you the sense, if you read his book with any empathy, that you may not understand the meaning, but there is meaning. God has meaning because it's all part of a plan. And it's moving, as Martin Luther King would later say the arc of the world bends toward justice. Well, who knows? But that was a conviction, and is a conviction that a lot of people want to see, that there's some kind of justice in the world, some kind of meaning, anyway. Even felt.

MARTIN NOWAK: Jesus predicts the destruction of the temple as we read in the New Testament, but that was written after the destruction of the temple but do they have any historical evidence that they have written predictions, or was it actually written after the fact? And the second, question John of Patmos, did he have access to some of the New Testament writings like Mark's Gospel?

ELAINE PAGELS: There's no evidence that he read anything like that. The only things we can tell that he read all the time were the prophets. Yes, what you say is what we all learned in graduate school, that Jesus couldn't have predicted the fall of the temple, that it was obviously added after his death. I am not convinced of that. If you read Josephus's The Jewish War, He tells about Jesus Ben Ananias.

Josephus, who was a general in Galilee and a governor of Galilee, and fought in the Jewish War against Rome, says that there was a prophet, a crazy prophet named Jesus Ben Ananias, who in the year 62, in Jerusalem, was going around and predicting the destruction of Jerusalem. Jerusalem wasn't destroyed until eight years later. But Jesus Ben Ananias prophesied it. Now, this would make sense if he, if Jesus of Nazareth, Jesus Ben Ananias, John the Baptist and others, were convinced that the temple cult, having been taken over by the Romans, had been completely corrupted, was no longer the worship of God. And God was eventually going to destroy that temple just as he had destroyed the first temple.

The other thing is I can't imagine anybody just making up, like Jesus prophesied the end of the temple. If Jesus had actually said it, which he could well have said, that would have been something that would galvanize somebody. But would you take a dead prophet and say that he had actually prophesied the destruction of the World Trade Towers, 30 years earlier, if there was no suggestion of such a thing? I think if he had said something like that, then it would have provided the enormous excitement and impetus for people who said he had actually prophesied what happened. And that would mean that the end of the world was coming. How else could you possibly believe a message like this?

Also, if you were making up a prophecy after the fact, what would you say? You wouldn't say not one stone shall be standing on another. You've probably been in Jerusalem, right? Many people here have been there. There are lots of stones of the temple remaining. The Romans threw them down, but there are many stones standing, so you wouldn't make up a prophecy that completely contradicts what actually happened. If Jesus had said, not one stone shall be standing on another, and that's not what happened, you'd have done better. But you would remember if he'd said something dramatic like that, even if it didn't literally come true. That's what convinces me that it's more likely that he said it. But who knows? Maybe they made it up. I don't see how they would have had the energy to start this movement, though.

JOHN TOOBY: If you look at what I think of as parallels in systems of thought for people who are losing in a power system, and they look ahead, they don't want to give up their identity. They're looking ahead, using this apocalyptic way of thinking. If you look at survivalists, for example, they say "we're just objectively predicting civilization is going to fall". But in fact they're hoping for it, because it will transform the social structure from one in which they are marginalized to one where they're players. Or if you look at the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo, initially it was "we prophesy—and we have nothing to do with this—we prophesy that there will be a civilizational collapse. Then we will flourish". But then they start to go beyond prediction, and use technology, taking lives with Sarin gas.

It always seemed to me The Book of Revelation fits right in there with other kinds of Essene writings about how the last will be first and the first shall be last. "You can't arrest us for this, because we're not recommending it. We're just telling you that's what's going to happen". But it has this function, as you said, of not standing up and saying, "We are going to resist militarily. Instead, we're going to bide our time. We're going to send out cultural signals. We're going to gather together people who are like us. We're going to be opposed to our enemies and form a larger coalition". Again, at the same time, they're disguising their stance to some minimal extent by saying "we're just foretelling the future, we're not acting".

ELAINE PAGELS: Right. It's people facing overwhelming military odds. They had not a chance. You see this also, that the ANC, Allen Boesak in South Africa, before Mandela was returned and all that, saw the end of the world. Right? And the collapse of the world. The reversal of the world as we know it. It's going to change completely, in The Book of Revelation. That's how we interpret it. And that's why I think African Americans also said this old world's going to reel and rock, it's about the destruction of the world as we know it. And those who are on the bottom are going to rule. It's a powerful way of transforming in the imagination. It may be fallacious, but it seems to work, and I'm interested in what other people think about how the brain works.

STEVEN PINKER: It seems to work as a remarkably compelling archetype. And you mentioned all of the successors, including Nazism, that had similar visions; and the matter of Communism, there's the dialectical struggle, there will be an enormous cataclysm. There'll be the take over by the Proletariats. Ahmadinejad prophesying, by some accounts, the return of the 12th Imam, although he denies it. But according to common attribution, there'll be a great conflagration, followed by Utopia.

These all seem, though, as compelling as they are, at least by modern standards, to be quite pernicious in that they vindicate the old revolutionary slogan, the worse the better, as if the more chaos, suffering, disease and so on, well, it may seem bad, but it's just the necessary last step before eternal bliss. Rather that combatting it let's just hurry it along, have this great orgasm of destruction followed by an eternal peace. And as part of this divinely unfolding plan, leading to eternal happiness, there's going to be an enormous amount of deaths of evil people, also a necessary step for the coming Utopia. I find this absolutely gripping, especially at the historical and the human level, it's fantastic entertainment. On the other hand the moralist in me is aghast and horrified. This is the worst possible vision of human improvement and advancement that the human mind.

STEWART BRAND: Compare it to the Rapture.

STEVEN PINKER: I don't know enough about the Rapture, either in the original formulation or the Left Behind novels. But it doesn't sound like a good thing.

ELAINE PAGELS: Steven, you were talking yesterday about war. This is about conflict, right? This is a way to interpret conflict. And what's one of the powerful elements of it is that there's good forces against evil forces. That is, whoever we think we are against whoever they are. And it has a structure, apocalyptic structure, that radical Muslims use, that many other people use. It's also the structure of something like the Wizard of Oz, or Lord of the Rings, or Star Wars. It's the forces of good against Luke Skywalker, against Darth Vader. It's this interpretation of conflict, as we're going to destroy the evil others. And that's what you were identifying.

What's interesting to me is that these other revelation texts have a very expanded vision. I'm an apologist for the others that didn't make it in. Athanasius didn't want them in, because he wanted to show that the Catholic Church consisted of all the people who would go into heaven, and everybody else was going into eternal torment forever. If you walk out of a church in Europe, you walk out the back door of the Sistine Chapel, the last judgment is the last thing you see. When you walk out the door, you stand warned, right? You walk out the door, and you ignore it, and you're on the wrong side, you're out of luck.

These other texts which Athanasius hated, have an expanded vision of not only the human race as a whole, but all being as a whole. I find them much more appealing as an understanding of the human race at this point in history. Because, can we really afford this kind of vision any more? No.

STEVEN PINKER: Is this is the source of the doctrine that sinners spend eternity in hell after being judged? Is it the first appearance in the Canon?

ELAINE PAGELS: It's very interesting. If you look at the teachings, there's very little in Christian teaching about this, but Jesus is said to have said when people say, well, okay, the Last Judgment, when God judges the world, how will he judge it? And the answer is the parable of the sheep and the goats. I was naked and you took me in. I was imprisoned and you visited me. I was sick and you took care of me, and so forth. The people who act with compassion are the people who go into the kingdom of heaven. This is traditional Jewish ethics. Right? This compassion for the needy, and the widow and the orphan and so forth.

But The Book of Revelation skips all of the acts, and just says, oh, who goes into the lake of fire? It's the filthy, the dogs, the abominable. They're described with epithets, not with acts. It has nothing to do with that. You could fit anybody you don't like. The filthy, the abominable, the dogs.

MARTIN NOWAK: I would like to add there is no such doctrine that people will be condemned. There's the possibility that everybody actually will be saved.

ELAINE PAGELS: I don't know in what teaching you're discussing, but in this book …

MARTIN NOWAK: The Catholic Church.

ELAINE PAGELS: Well, the Church is 2000 years of traditions. In this book, some people definitely go into the lake of fire and stay there forever, eternally tormented. And other people go into the heavenly Jerusalem. At least that's the visual and emotional impact of the story, it seems to me.

STEWART BRAND: Something I'd love to see added to this talk is the other revelations. I don't know if you have such gorgeous illustrations for them, those are fantastic illustrations. But just to give some of the sense of their poetry and what they're about, and how inclusive they are, and basically give an alternative, less pernicious, of what revelations can be. And that gives us more perspective on what an amazing thing the decision to include this book was.

ELAINE PAGELS: Exactly. And that's really what interested me here. I have some little hors d'oeuvres from the other ones. For example, The Secret Revelation of John. This is a secret revelation of John that was found in Nag Hamaddi, combining with the Secret Gospels.

STEWART BRAND: Same John?

ELAINE PAGELS: It's supposed to be the same John. And Jesus appears to him. This is the Secret Revelation. And he says, "Christ, will the souls of everyone live in the pure light? He said to me, those on whom the spirit of life descends will be saved and become perfect. The power enters into every human being. Without it, they couldn't even stand upright." So the idea is you couldn't walk if the spirit hadn't given you life. It's given to everyone, at least potentially.

And the other revelations, Trimorphic Protennoia is one that I like. It means in Greek, the triple formed primal thought. It's a mystical Jewish text about the transcendent aspect of God is completely unknowable, and therefore, higher and masculine. The imminent aspect of God, later called Shekhineh, or Ruach, or Hochma, all feminine terms, wisdom, spirit, presence, is feminine. And she is somehow manifest in the world, and she speaks in this text. She says, I am Protennoia. That is, the primordial thought who exists in the light. I am the movement that lives in all things. I move in every creature. I cry out in every creature.

MARTIN NOWAK: This is exactly in the Bhagavad-Gita. It is not Christian.

ELAINE PAGELS: Yes, and it could well be connected with Indian tradition. But I think this comes out of Genesis traditions, Jewish mystical tradition.

MARTIN NOWAK: When was this written?

ELAINE PAGELS: This is at least around 120, 130 of the common year. These mystical teachings, and there are others, too, that speak in exactly that vein, about the presence of the divine in everyone, potentially. But that's completely not what the church chose.

MARTIN NOWAK: But I noticed that the spirit of God is in everybody.

ELAINE PAGELS: This is found with the Gospel of Thomas and the Gospel of Phillip. Then there's one called Thunder, Perfect Mind, which is about the divine thunder, seen of course, in Greece as the voice of Zeus, seen in the Gospel of John as the voice of God, that Jesus hears thunder. And here, Thunder speaks, and says, she is everywhere. But you have to recognize who she is. And she is in everyone. In everything. She says, "I am the first and the last. I am the honored one and the one that is scorned. I am the whore and the holy one. I am the wife and the virgin, the mother and the daughter." Again, a feminine image for the manifestation of God in all beings.

STEWART BRAND: Boy does that flip the Whore of Babylon.

ELAINE PAGELS: Yes, it does, because there's no whore, or the virgin. That's what you find in John. They're all completely divided. It's God and Satan. In this, it's much more like a Hindu…

MARTIN NOWAK: The doctrine of absolute monism.

ELAINE PAGELS: Yes, it is. It is very much in that vein.

STEWART BRAND: A slide with those hors' d'oeuvres, should close with that.

ELAINE PAGELS: Yes, I like that, because this is probably a poem that was taken from Isis hymns. Hymns to the Goddess Isis. But it also uses the image of Eve. She says that "I am the one whose name is Life, and they call me death." Because she's supposed to bring death into the world. But here, she is both life and death.

LEDA COSMIDES: There might be some hints as to why some of these were more appealing to some factions than to others.

So we're here in a room. We're not trying to organize a religion or any kind of coalition, or overthrow the Romans or anything. And these books of revelation that did not make it into the Canon, sound appealing to us, and it's nice, right? But in the psychology of collective action, with the problem of free riders, there's an interesting thing about how newcomers are viewed. And this is done not in the context of religion, but in the context of any kind of group or fraternity, or hazings and so on, which is that newcomers are, they're coming into the group. They're in a position to get the benefits of being in that group, but they haven't put in the same contributions to that group that the long-term veterans of that group have. And so there's some sense in which they're free riding on the past efforts of the others, and that these impulses toward hazing and so forth. Some of our colleagues have worked on the psychology of newcomers. If you're trying to put together a coalition, you are describing the kind of horror that John of Patmos must have felt at this idea that, well, anybody can become a Christian. Anybody. They don't have to do anything. They don't have to do the hard work. They don't have to keep kosher. They don't have to do our initiations. They don't have to do the things we do.

JARON LANIER: But don't forget circumcision!

ELAINE PAGELS: That could be a deal breaker…

LEDA COSMIDES: And so if you think about the different kinds of parties that are involved here, people who are trying to build a particular kind of coalition might have a very different attitude towards a doctrine that views newcomers as they're just as okay as anybody else, compared to one that says, no, you have to contribute to this coalition. you have to really uphold these values and so forth. And so there's all these different parties, some of whom are going to have one attitude towards the newcomers who don't have to do anything, then others who are not trying to build the coalition, but just have these different kinds of attitudes that come out of an evolved psychology that is in all of those for completely different reasons. But that's why some things will resonate more with some people than with others. Some people want to keep all this other stuff out, this other stuff that says you don't even have to try hard. You can just be there.

ELAINE PAGELS: I see your point.

STEVEN PINKER: This speaks to the original question of why a lot of these beliefs persist. And I'm always puzzled how, if you take all of this literally as some profess to do, that it really does lead to some — and speaking anachronistically as a post-enlightenment secular humanist — it leads to all kinds of pernicious consequences. Like if the only thing that keeps you from an eternity of torment is accepting Jesus as your savior, well, if you torture someone until they embrace Jesus, you're doing them the biggest favor of their lives. It's better a few hours now than all eternity. And if someone is leading people away from this kind of salvation, well, they're the most evil Typhoid Mary that you can imagine, and exterminating them would be a public health measure because they are luring people into an eternity of torment, and there could be nothing more evil. Again, it's totally anachronistic. The idea of damnation and hell is, by modern standards, a morally pernicious concept. If you take it literally, though, then of course torturing Jews and atheists and heretics and so on, is actually a very responsible public health measure. Nowadays, people both profess to believe in The Book of Revelation, and they also don't think it's a good idea to torture Jews and heretics and atheists.

ELAINE PAGELS: Maybe they just don't have the power.

STEVEN PINKER: Even the televangelists who are thundering from their pulpits, probably don't think it's a good idea to torture Jews. And in fact, in public opinion polls, there's a remarkable change through the 20th century, in statements like, all religions are equally valid, and ought to be respected. which today, the majority of Americans agree with. And in the 1930s, needless to say, the majority disagreed with. What I find fascinating is, what kind of compartmentalization allows, on the one hand, people to believe in a literal truth of judgment day, eternal torment, but they no longer, as they once did, follow through the implication, well, we'd better execute heretics and torture nonbelievers. On one hand they've got admirably, a kind of post-enlightenment ecumenical tolerant humanism, torturing people is bad. On the other hand, they claim to hold beliefs that logically imply that torturing heretics would be an excellent thing. It's interesting that the human mind can embrace these contradictions and that fortunately for all of us, the humanistic sentiments trump the, at least, claimed belief in the literal truth of all of this.

ELAINE PAGELS: Well, that's certainly an important point. It's about 20 years, maybe … no, it's about 13 years after the acceptance of this Canon, that it becomes a capital crime to convert someone to Judaism or heresy in the Roman Empire. But I don't think you have to take it literally to take it very seriously. I've been living in Colorado, and I heard Rick Warren say that somebody asked him whether Jews could be saved, and he said, well I'm not God, he said, but I really don't think so.

STEVEN PINKER: He may be God, in other words.

ELAINE PAGELS: Even if you don't take any of this literally, is it conceivable that this interpretation of conflict is really part of our cultural paean It has been. And it has many uses, obviously.

STEVEN PINKER: On the other hand, though, both Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela did achieve fantastic change without a huge cataclysm and disaster, and bloody conflict, and qualitative transition to a different world. It's interesting that they borrow the imagery, but in the actual day to day game plan, it was much more pragmatic, practical, humanistic.

ELAINE PAGELS: And it had a much more capacious vision. I would like to see this one become obsolete to some extent.

STEWART BRAND: What if it's like violent movies, it's a displacement of violence, of something you do to somebody else, to something that God does to somebody else. But it's not your job to do it because you're not God, as pointed out in Colorado, and that's actually a kind of a release? Maybe that was part of the original idea. I doubt it.

ELAINE PAGELS: Could be.

JARON LANIER: You should look into Singularity culture, which has many varieties. It is a high tech continuation of Revelation.

STEVEN PINKER: Oh, but there's no capitalism there. It doesn't have to get worse before it gets better, right?

JARON LANIER: Sometimes the idea is that humankind will be eaten by nanorobots in the flesh, but we'll also be virtualized and living in heaven in virtual reality. These ideas have a serious influence in technology culture. There's a Singularity Institute in the old NASA facility in Mountain View, by Google.

It’s interesting to take a game theory approach to metaphysics. If you're in a game, and you become skilled enough to competently take action to change the game, it's incumbent upon you to hypothesize a meta-game. This is the context within which you can conceive whatever change you will make to the game you're playing.

Totally aside from the fear of death and all the emotion that's involved, metaphysics is also just a matter of logic for people who become competent at reinventing their lives. People who are within a game, but become skilled enough to change the game, are compelled to imagine a meta-game, because it's the only way to think about it, so metaphysics is unavoidable. Usually in game theory experiments, you have the researcher imposing the game on the subjects, but in real life the subjects can actually start to change the games themselves.

This leads to the sort of meta-game theory.

In the singularity culture, a lot of the really bright young computer scientists foresee transforming all of reality to a computed thing. They get a certain glow when they seize on a new meta-game of everything becoming more optimized or more globally computed, for instance.

STEWART BRAND: But what's our end game scenario? In a way, the opposite of all these, the Rapture and the Revelations is James P. Carse's "The Infinite Game".

JARON LANIER: That's a very good thing to bring up.

STEWART BRAND: You have the latitude in competitive games to say there's only one game. And it's an infinite game, and you've got to keep the game going, you constantly improve the rules. That should be through the meta. And that's the total opposite of these end games.

JARON LANIER: I bring up Carse all the time when I'm trying to talk to computer science students who've become, at least in my opinion, a little goofy about singularity thinking which comes up incredibly often now. In fact I'd say more often than not. And the brighter the student, the more likely they are to get lost in it.

Return to Edge Master Class 2011: The Science of Human Nature

|

"We'd certainly be better off if everyone sampled the fabulous Edge symposium, which, like the best in science, is modest and daring all at once." — David Brooks, New York Times column

Future Science, edited by Max Brockman 18 original essays by the brightest young minds in science: Kevin P. Hand - Felix Warneken - William McEwan - Anthony Aguirre -Daniela Kaufer and Darlene Francis - Jon Kleinberg - Coren Apicella - Laurie R. Santos - Jennifer Jacquet - Kirsten Bomblies - Asif A. Ghazanfar - Naomi I. Eisenberger - Joshua Knobe - Fiery Cushman - Liane Young - Daniel Haun - Joan Y. Chiao "A fascinating and very readable summary of the latest thinking on human behaviour." — [More]

"Cool and thought-provoking material. ... so hip." — Washington Post The Best of Edge: The Mind, edited by John Brockman 18 conversations and essays on the brain, memory, personality and happiness: Steven Pinker - George Lakoff - Joseph LeDoux -Geoffrey Miller - Steven Rose - Frank Sulloway - V.S. Ramachandran - Nicholas Humphrey - Philip Zimbardo - Martin Seligman -Stanislas Dehaene - Simon Baron-Cohen - Robert Sapolsky - Alison Gopnik - David Lykken - Jonathan Haidt "For the past 15 years, literary-agent-turned-crusader-of-human-progress John Brockman has been a remarkable curator of curiosity, long before either "curator" or "curiosity" was a frivolously tossed around buzzword. His Edge.org has become an epicenter of bleeding-edge insight across science, technology and beyond, hosting conversations with some of our era's greatest thinkers (and, once a year, asking them some big questions). Last month marked the release of The Mind, the first volume in The Best of Edge Series, presenting eighteen provocative, landmark pieces—essays, interviews, transcribed talks—from the Edge archive. The anthology reads like a who's who ... across psychology, evolutionary biology, social science, technology, and more. And, perhaps equally interestingly, the tome—most of the materials in which are available for free online—is an implicit manifesto for the enduring power of books as curatorial capsules of ideas." "(A) treasure chest ... A coffer of cutting-edge contemporary thought, The Mind contains the building blocks of tomorrow's history book—whatever medium they may come in—and invites a provocative peer forward as we gaze back at some of the most defining ideas of our time." — [More] The Best of Edge: Culture, edited by John Brockman

17 conversations and essays on art, society, power and technology: Daniel C. Dennett - Jared Diamond - Denis Dutton - Brian Eno -Stewart Brand - George Dyson - David Gelernter - Karl Sigmund - Jaron Lanier - Nicholas A. Christakis - Douglas Rushkoff - Evgeny Morozov - Clay Shirky - W. Brian Arthur - W. Daniel Hillis - Richard Foreman - Frank Schirrmacher "We've already ravished The Mind -- the first in a series of anthologies by Edge.org editor John Brockman, curating 15 years' worth of the most provocative thinking on major facets of science, culture, and intellectual life. On its trails comes Culture: Leading Scientists Explore Societies, Art, Power, and Technology—a treasure chest of insight true to the promise of its title. From the origin and social purpose of art to how technology shapes civilization to the Internet as a force of democracy and despotism, the 17 pieces exude the kind of intellectual inquiry and cultural curiosity that give progress its wings. (A) lavish cerebral feast ... one of this year's most significant time-capsules of contemporary thought." —[More] |