RICHARD THALER: I'm going to describe a proposal, and it's a solution. And we're going to work on the problem for which it is a solution, and you will have a lot to say about how it would work if it were a solution to some problem.

Here is the idea. I'm going to call it electronic disclosure. Let me say how it would work for credit cards. The idea is, for every credit card you have, the card company would be required once a year to send you two electronic files. The first file would be essentially a spreadsheet of all the formulas for all the ways they can charge you for things. If you make a payment a week late and they charge you $20 and raise your interest rate, that's in there. If you spend a week in Europe and they charge you three percent to convert currencies, that's in there. Everything is in there. That's the first file.

The second file is a list of all the things you did in the past year that incurred charges, or could have incurred charges. For example, here's a tip: Capital One doesn't charge for foreign currency transfers. If you have a Capital One and you make foreign currency transfers that would be in the list of things you would have been charged if you had another use for it.

The second file is the list of things you were charged for. It might say you were charged $1,800 for this credit card in the past year, $1,200 of that was interest payments, this was for late fees, these were for currency transfers, and so forth. We don't think anybody would ever look at those files. What we think is that websites would emerge immediately that would process that information and those websites would serve the following purposes.

First is a translation. They would explain to the user what is happening to them in plain English. The second is behavior modification. They would explain to you that you paid $1,800 because you were clueless about paying your bills on time. If you got automatic payment, you would save a lot of money. The third would be comparison-shopping. Notice that with this information they know your usage patterns, they know all the formulas for all the credit card companies, they can search and find three credit card companies that for the way you use your credit cards would be better for you. That's the concept.

Let me give a few domains where you could use this idea.

One is mortgages. Right now we have consumer regulation that says you get 30 pages of plain English that describes the mortgage that nobody understands. What this would say is in addition to that you get this file. Now websites compete at explaining what those files mean. As part of my learning process, I went to Lending Tree this week to search for a mortgage. As far as I can tell, they do essentially none of this. They get me quotes but don't give me any help in figuring out how to compare a five-year ARM versus a three-year ARM that is set to a different formula or what are the pre-pay penalties. I suspect they can't do that because they don't have the information.

BEZOS: Also, they are being paid. It's the fox in charge of the hen house.

THALER: Right. That brings up another very important point that I would love to have a discussion about, which is, what is the right business model for those websites? Take the travel websites. I told some of you my story about Hertz but let me share it with everyone because it's an illustration of the kind of problem we are trying to solve. All of us smart consumers know to turn down the insurance when we rent a car because it's covered by our credit card. When I rented a car in Ireland for my co-author's wedding, I was charged 25 Euros for declining the insurance. I said, what's this? They said we have to fill out a lot of forms for your declining the insurance and it comes under administrative fee, 25 Euros.

I haven't done my homework on this but I'm pretty sure that it would be very hard find that fee on Orbitz or Expedia. The hotels and airlines and car rental companies pay them. Another example is we were in hotel in Miami. It cost $45 to park the car. It was difficult to find that data when you were searching for a hotel. I talked to a student of mine who works at Orbitz and she said, well, we rely on the hotels. The hotels pay us and they have to give us inventory, and if they don't give us inventory we can't sell any rooms, and if we made them look bad they might not give us any rooms.

The business model issue is very interesting. Ideally you want somebody like Google that seems to be very good at having a reputation as an independent third party. Let me say one last thing about this.

The Fed is now in the process of writing new credit card regulations. It consists of a list of do's and don'ts. I don't know whether this one is in there but it might be. You can't charge interest on the penalty. The guy in charge of writing these, Randy Kroszner, is a colleague of mine at the University of Chicago. He is on the Board. He's a good economist. He knows that that you can have that rule. You don't have a rule about what penalty they can charge you. Right? It's whack-a-mole.

My big claim is that in principle if you had full electronic disclosure, you would be able to stop having all of those silly rules and regulations because the market would take care of it because you make consumers smart.

MYHRVOLD: Doesn't Capital One already spend a tremendous amount of money arguing that they are that provider? In this case there is someone who has decided to break from the pack and do that and other people don't. Jeff made a decision at some point, or some smart guy there did, the relationship to the customer is more important than to the booksellers so they put on reviews, including bad reviews, and they put on second-hand sources of books besides new sources of books. Both were hugely controversial but ultimately his relationship is with the customer. He was popular enough that those other constituencies had to accept it.

KAMANGAR: Nathan's point also applies to Richard's travel website example. An example of a consumer-friendly business model is one that's ad-based, assuming of course the advertisers are not the businesses featured by the travel website. This model aligns the travel site's incentives correctly, because the more they're focused on pleasing the user instead of the travel businesses they're reviewing, the more traffic they'll get, and the more advertising revenue they will take in.

MYHRVOLD: That's one approach, but even if its not ad supported, if you have enough power in the relationship because you have a strong enough customer composition, than you can say no. It turns out we'll include these zero-star reviews on Amazon and we'll include the used bookseller and too bad, publisher. It's better for the customer. If customers didn't like it very much, then he wouldn't have a very good proposition.

THALER: I don't know enough about this to know why there are no travel websites that are not on a different business model.

KAHNEMAN: Is there a model where people pay just for information? That's the question.

MYHRVOLD: Sure. There are in travel a zillion sites that are rating and very consumer oriented. They typically won't take advertising. Advertising is better in some ways but not in others. There's a whole advice thing.

HILLIS: But is it better because it's a model where people pay for not having to deal with information. In some sense people are willing to pay knowing that they pay a premium for not having to optimize.

BEZOS: This is that cognitive load issue.

MYHRVOLD: Right. There are still travel agents that are high-end travel agents. They have not all gone away. 100 percent of the market isn't Expedia.

ROMER: There is a market where you have seen this tried where it had never taken off, which is fee-based financial planning. There are people who say for a fee we'll be your financial planner. One of the interesting things is if you contact a fee-based financial planner what they will send you is, be careful, the people who are competing with me, here are all the subtle ways that they could be taking kickbacks that you might not know about. There are people, who claim to be fee based, but they're getting rebates, they're getting contests and so forth. Underlying this there is a regressive information disclosure problem. If somebody says he's fee based, how do you know that they are not getting secret fees in the background? This may be part of why fee-based financial planning has never taken off.

KAMANGAR: About financial planners, high net-worth ones, they get benefits from being associated with certain groups, individuals. That's social in nature. You're part of the Goldman Sachs club, you get these things. That adds up.

THALER: They get invited to conferences. I spoke at a conference sponsored by a big money manager years ago where the keynote speaker was Jay Leno. It was at the Four Seasons, Carlsbad. The clients were like a Midwestern city's Fireman's Association that was investing with these guys and it's clear that they were never going to fire that money manager.

The big claim here is that by requiring disclosure we can create websites that are impossible now. A good example is Morningstar. Morningstar exists for mutual funds but not for hedge funds because hedge funds are not required to disclose their information and mutual funds are. There is no way to search for mortgages, as far as I know, or credit cards, or Medicare Part D, which is where we got the idea for this.

MYHRVOLD: There are two solutions to this. One solution would be, that Sean Parker will fund you in a start-up to say here is the first customer-oriented mortgage thing. There is a gap in the market for such a player. Lending Tree is pretty pathetic in lots of different ways but including it doesn't have that customer focus. Hey you can go do that, as a customer-focused mortgage source and you can go do what he's done in books, but do it for mortgages. That's one approach. The other approach is to say, no, we have to mandate a whole bunch of complicated information that we think will make it easier for a bunch of people to go do that, but it's not obvious particularly in this case, I don't see why it can't be done. The world hasn't done it yet.

BEZOS: There is an interesting general idea here, which is machine-readable disclosure. If disclosure is already going to be required, why not make it machine-readable? To me that has legs.

MYHRVOLD: It's a very clever aspect. Absolutely.

ROMER: But it will require some standardization of the products people can offer because any machine-readable format is going to have to have a finite number of variations. You're going to buy into some regulation of standardization.

BEZOS: But as opposed to a set of rules, as someone said earlier, the set of rules is horrible for innovation, whereas the disclosure is going to be less onerous.

THALER: Here is the way I view this working. Let's take cell phones. iPhone comes out with a new model that does things that nobody has ever been able to do on a cell phone before. All they would have to do in my ideal world is write an application to the regulator to have three new lines added to the spreadsheet.

MYHRVOLD: You could do it all in XML and make it self-describing instead of having to ask.

THALER: Well, essentially we want the disclosure to be uniform.

BEZOS: That is going to be difficult. But people can write different applications to interpret the different non-uniform disclosures.

THALER: If you allow non-uniform, then you are opening yourself up to all kinds of chicanery.

MYHRVOLD: Why don't you think there is a market solution to this?

THALER: This is a market solution.

MYHRVOLD: Why do you think there has to be a mandated czar of disclosure? Then explain 10Q reports to me because there is one where there is such a thing and so much human cleverness goes into obfuscating what goes into those deals, it's very unclear that there is any net benefit.

THALER: We could have an argument about whether we would be better off or worse off without the SEC.

MYHRVOLD: It wasn't about the SEC broadly. There is a set of disclosure things that insane amounts of IQ go into gaming.

HILLIS: I don't understand. Here's a basic question. Right now there are mandated disclosure things for credit cards, right?

THALER: Yes. But they're all in writing.

HILLIS: You're suggesting that that same set of things be required to be done in some machine-readable format. There is a sub-discussion about who should establish the format.

MYHRVOLD: It's a cool idea. The other thing is I'm asking if he believes that that cool idea must originate by a governmental regulation. I'm most curious about that.

MULLAINATHAN: There is a second part of the idea before we get to the regulation that is missed by calling it machine readability, which is, think of a set of goods for which there is kind of homogeneous demand. I'm going to a hotel; I would like to know if my room has a bathroom, etcetera. These are things I want to know. A disclosure might say that such things should be disclosed. We can talk about whether that is machine disclosed or not. But Dick is talking about a set of goods where the characteristics of the good alone are not enough for you to be able to understand the good. You have to match the characteristics of the good with some feature about yourself.

HILLIS: You're also asking disclosure of your own behavior back to you.

MULLAINATHAN: I would not disclose my own behavior because that leads to complications for me. You could say I disclose the details to you. Go back and look at the credit report, you figure it out, match the vector. Dick is saying can we create a secure disclosure of my characteristics, like my past utilization, so that somebody can take that. I'm clarifying.

MYHRVOLD: The answer is of course you can.

BEZOS: In the old days when people paid for long distance phone calls, where the companies would set up and say, give me your long distance phone bills and I'll tell you how you would have saved money and how much. They would analyze it, mostly to businesses.

THALER: Right. There is a company in Chicago that is doing the credit card thing for businesses. There isn't anybody who does this for cell phones, and the reason is that it's too expensive. I would have to mail you my 12 monthly statements to get all of this information. Nathan's question about whether we need the government to mandate it is one of the things we should talk about it. We don't have it now. Let's take the cell phone companies. I don't see any reason to think that they would give this information out if they weren't required to. We need to mandate it.

BEZOS: One of them might say you should choose me because I do give this information out.

MYHRVOLD: Which is what Capital One does in the credit card case. There are some people who do that. It may not be fully true but that is their posturing.

THALER: You're giving Capital One way too much credit. I recently got one when I figured out that they have this foreign currency thing. First of all, that never appears anywhere on their website shockingly.

BEZOS: Maybe they just forget to charge for it!

THALER: Then the sign up form is totally bizarre. It asks you whether you want two miles per dollar or one. Wait a minute? Am I missing something here?

MUSK: I'm not totally clear. You're saying that there isn't enough regulation, particularly in certain sectors there should be more, and that would be better than market forces in some cases. Is that correct?

THALER: No. I'm saying we need less regulation because the regulation we have now is stupid and that we should replace all of that with one regulation which is just disclosure in a machine-readable form. That's my proposal.

HILLIS: Here is an alternate. The state where you want to get to is where you would have disclosure in a machine-readable form.

THALER: Right.

HILLIS: There is a sub-discussion as to whether the best way to get to that state is by creating a law that says that. That's an interesting one. But Jeff also raised another interesting point that may help you get to that point, which is, if you generalize the idea of machine-readable disclosure, it solves another problem with why these things don't work. Another reason why, for instance, the phone thing doesn't work is that it's too much trouble to know about the phone company that does the optimization and the company that does your insurance optimization and the company that does your finance. That's too high a cognitive load. But in fact if you generalize this concept and you got to the point where all things that were complicated, every kind of disclosure that people made to you about a complicated product, was done in machine-readable format, then a kind of company could go which is like a bank.

THALER: Think of it as Super Quicken.

HILLIS: You trust these guys because across the board they help you make these judgments. A lot of the reason this hasn't caught on is because the guiding proposition isn't so great if it's piecemeal.

MYHRVOLD: That's one reason. The other reason is standards require a standards dictator. It turns out the way commercial standards work that are successful is that there is somebody in charge of making sure that the standard is followed, and it's very hard to be proscriptive about it up front. Some of it is reactive to what other people do. There is a whole pile of companies whose entire job, their value proposition in the world, is helping maintain those standards. They are always involved in high stakes negotiation and fighting with other companies. Cisco, de facto, does a whole variety of standards around local area networking. And Qualcomm and a variety of other companies do that. The GSM companies do it for GSM, Qualcomm does it for CDMA.

It's very hard to put a static government bureaucrat in that job because you need to have someone who has enough independent authority and power to do it. If you had a government bureaucrat in charge of deciding whether the used books would be displayed on the same page as the new books, someone would flim-flam that guy.

BEZOS: It's worse because bureaucracies exist to protect the status quo. Bureaucracies have huge status quo bias. How we're doing it now, that's the way we should do it. It's very backward looking.

THALER: I don't disagree with any of that, but I also believe that if we had this disclosure, it would change everything.

MUSK: I doubt it. It sounds simple but the implementation is going to force a lot of regulation in order to figure out what information should be displayed and what should not be displayed because you can obfuscate by over-explaining information. When Germany attacked France, France was aware that Germany was going to attack because they broadcast it. That was the 20th time they had broadcast it.

MYHRVOLD: There are all kinds of regulations about financial disclosure on a variety of things. But try to buy an coop apartment in New York City and you will discover the coop board of that apartment building has more ability to ask you things than anyone would ever be empowered any other way because of the way the market forces have got it set in New York City, plus you get enough hard-ass attorneys with nice apartments, they don't want lousy neighbors. There is a private vetting process that is much harder than anything you ever could have regulated.

BEZOS: Bend over and cough.

MYHRVOLD: Yes. Exactly.

THALER: Let's go on. I have a response to your comment which is you are essentially saying there is information overload.

MUSK: It's one way to game the system.

THALER: I disagree with that and the reason is that the websites that I imagine emerging solve that problem. It is true that when I first got my iPhone and I got my first statement‚ it was 90 pages because every time you looked at a website, that was an event. They now put it online but of course nobody is ever going to use that. Maybe they are trying to game the system somehow but it doesn't matter in my world because the cellphone.com is going to digest all of that for me. It seems like the substantive argument that I'm hearing is that the process of determining what the things are in the list is so hard that it will squash innovation; or that the process of determining the characteristics is so hard.

MYHRVOLD: Don't panic to the extreme. There is a lot of value in what you propose. But it's not the panacea quite that you have made it out to be. It incrementally makes it easier to have cellphone.com, this kind of analysis business, which is more difficult to do today. But it's also not impossible to do today. I would argue that the way that this would be maintained going forward is, if the cellphone.com CEO is smart and that company becomes successful, they will have the market power to be able to say we're going to require a new kind of disclosure. We don't care what the government is saying. We're going to put a black star next to you if you don't disclose this. Ultimately that would be more powerful than the government bureaucrat who kicks it off.

THALER: That's a good point.

MUSK: There are some good systems. Amazon does it well. There is so much information about a product. You get editorial reviews. You get user reviews. You can see what the sales rank is. Ebay also. You can see if the seller's reputation is good or bad, how many people have been upset with them. There are all kinds of mechanisms on the web and there will be more over time that will solve problems such as this one. I agree. You're not going to get push back if you say let's make things machine-readable, it will make it easier to do reviews. I agree with that. But I don't think it's going to change the world in a major way.

THALER: I'll go back to my previous statement, if I could make the world two percent better off, that's all right.

MYHRVOLD: Absolutely.

THALER: When I say it changes everything, what I mean by that is in my narrow economist hat that it would very much change the way economists think about regulating these markets.

MYHRVOLD: The flip side of that is there are lots of people who have businesses a little bit analogous to what you are saying that are afraid the privacy regulation will prevent them from doing new services. They are afraid that Salar is keeping all of our queries, which he undoubtedly is.

THALER: A large "no comment" sign over here.

MYHRVOLD: There certainly are ways that you could hurt or help it. By publishing data in machine-readable formats with a standards schema, it's not the standardization of the spreadsheet, it's that things have the same meaning. Or that you can parse what meaning is there. Having a standard schema for that information and making it something, which is expected by the public, regardless of whether you do that with a very strict rule or you do that with market force. There is a lot of value in that.

THALER: At a minimum, what we're saying is that in every market where there is now required written disclosure, you have to give the same information electronically and we think intelligently how best to do that. In a sentence that's the nature of the proposal.

KAHNEMAN: I have a question. Whether the market for decision aids, for individual decision aids, somebody wants to buy a car, somebody wants to buy an apartment in New York, it doesn't seem to be an obvious solution to that and it's odd because you would think that when you look up New York apartments in Google there would be a site that would say ....

BEZOS: There is a huge industry that helps people make car buys.

THALER: Car works pretty well.

KAHNEMAN: Let's analyze the condition under which that allows it. It's probably because the vocabulary of attributes is rather small.

BEZOS: The purchase price is big enough that it's worthwhile.

HILLIS: And that the characteristics are transparent enough that people can have trust that they could work for them. People can tell if they got a good price on a car, they can't tell that they got a good financial planner.

THALER: Right. Or mortgage. Mortgage is 10 times bigger than car in terms of the financial stakes. This does not exist in mortgages.

KAHNEMAN: But an example of what Dick was talking about with respect to cars was miles per gallon. It turns out that miles per gallon are terrible.

THALER: Gallons per mile is much better.

KAHNEMAN: Gallons per dollar or gallons per mile are better. It makes a big difference, by the way, about how understandable it is. It's not the same. That was done by regulation. I thought that's an example of the kind of thing that you were talking about.

ROMER: Another one that's a good example is when the FAA forced airlines to disclose route-by-route on-time performance of airlines. It completely changed behavior in the industry. You could have waited for a standards body and a private sector monopolist to come in, but it was a big benefit for everybody, because they were competing by giving false information about when you get there and it wasn't good as a way to compete.

MYHRVOLD: Sure. That's a good example.

THALER: Although, of course, they now add a half an hour to the expected arrival.

ROMER: Well, that's useful because you can plan on that more reliably.

THALER: That's true.

HILLIS: But if you think there is a great benefit here and this disclosure is right now, already happens to be made, but in textual form, then isn't there an opportunity for a company basically to convert that text to a machine-readable form, if there was a real benefit to it?

THALER: There are two answers to that. One is the personal. That doesn't exist. The second one is, if you take the example of credit cards, Capital One probably has 50 different credit cards. The one I get may be different from the one Paul gets.

HILLIS: There is no standard place where people have to file their disclosure?

THALER: They have to disclose some of the terms but the interest rate that you get and the way which it will change depending on what you do depends on your credit score and they change that all the time. There is no way to get that information.

HILLIS: You're asking for more disclosure, not just disclosure in a more machine-readable format.

THALER: I don't think so. Well, it's more disclosure in the sense that there would be a way for somebody to compare all the ways people are being charged, not do it one by one.

BEZOS: How does brand reputation play into this? I don't need a whole lot of disclosure to decide to buy a Toyota. There are companies that over decades build brand reputations and they earn trust, from their customer set. In fact, all the noise in the marketplace is a huge incentive for companies like Toyota to try to build that kind of brand reputation. Taking a long view, I wonder how you put that into this framework because companies that take that long view and earn trust benefit from this marketplace noise.

THALER: You're raising an interesting question, which is, when is it in the interest of the companies to obfuscate and does that help or hurt consumers? The fact that Hertz made it hard for me to find out that they were going to charge me 25 Euros not to take the insurance, why does Hertz think that is a profitable model? That is a company that here has done something in the opposite direction. The Hertz car I rented for this weekend, they will now fill your tank up for seven dollars rather than $12 per gallon. I view that as a consumer friendly switch. The same company that is the best brand name in the business is behaving badly in Ireland and well here.

MYHRVOLD: But Jeff's point is Nordstrom doesn't do that. Nordstrom has a very liberal return policy and everyone who is a Nordstrom customer knows they have a very liberal return policy. They ought to realize that also means they pay a little bit more but it doesn't matter. People are okay with it. Nordstrom's position is, yes, there are a million deals out there, but you've got a fair amount of trust with us. If you come back and you're unhappy, even because you see it cheaper or because you don't like the shoes, it doesn't matter, we'll take it back.

KAHNEMAN: It's my impression that now we're talking about paternalism because there are enough suckers out there to create an incentive for an alternative model that doesn't build on trust. You will have sophisticated people who will buy from trust-worthy suppliers, who will charge them more because they can be trusted. There are lots of other people who don't that. Part of the incentive for Dick's proposal is to protect the suckers. Or am I wrong?

ROMER: There is another point that is prior to that. Even with Econs as consumers, there is a tradeoff if you are relying on private sector mechanisms like reputation or private standard setting bodies. They coexist well with very vigorous competition. Reputations and private standard setting typically imply market power. If you could get the ideal form of government regulation, you could get disclosure.

BEZOS: You think Toyota has market power?

ROMER: Yes. But it's more market power than some industries.

MYHRVOLD: Jeff's point was the opposite of your point.

ROMER: There is a tradeoff there even before you get the paternalism that adds it further. There may be times where, say, the market power Toyota has is pretty small, the branding works pretty well, and that's a great solution. There may be other cases where market power problems might be bigger and you might rely on a more governmental mechanism. But that is at least a tradeoff.

MYHRVOLD: His point was a little different. His point was the opposite of what you're saying. His point was when there is a lot of noise, and when there is a lack of trust, then there is an opportunity for someone to become the trusted guy. It's almost the opposite of what you are saying. If there are lots of untrustworthy used car salesmen, there is an opportunity for someone potentially.

KAHNEMAN: My point was that person would attract only a small fraction of sophisticated customers.

MUSK: I don't know about that.

THALER: The question is a simple economics question. In these markets that involve some trust, when will markets get dominated by the trustworthy brand names and when will they be dominated by the sleaze bags? Take the mortgage crisis. Sleazy mortgage brokers generated a large proportion of the subprime loans. They were selling mortgages door to door. The way competition in that market works is the sleaziest guy wins because he describes a mortgage that sounds good. Paul comes and he's moderately honest and describes his mortgage and then Sendhil comes and he's not so honest and his mortgage is going to sound better than Paul's.

BEZOS: Here is a question. It's a very interesting point. If Toyota is a counter example and mortgages, these two are opposites, what are the characteristics of an industry where sleaze balls tend to win versus‚

THALER: Repeat business is number one.

BEZOS: But the repeat business on car is not that high‚ versus an industry where there are trusted straight shooters. I can tell you that Toyota sincerely tries to build an excellent automobile.

MUSK: The Toyota example is excellent. If 30 years ago the domestic makers made unreliable cars that were designed to break down after a certain period of time and then Toyota and Honda came into the market and said we're going to make reliable cars that last for a long time, in theory it should be counterproductive. People are going to be less likely to buy another Toyota sooner than they would a GM car. What happened is that people realized this and said I want a car that doesn't break down. Over time Toyota and Honda eroded market share away from GM and Ford and those guys are still suffering from their behavior today.

MULLAINATHAN: The key feature, which has already been mentioned, that has been overlooked is can you, after purchase, evaluate the hedonic value of the purchase or not? Can you do this with a car in three, four years. You could say that's a long time but it's not that long of a time, especially when you figure that in four years the thing breaks down.

BEZOS: That's very interesting. What about the Hertz example then?

MULLAINATHAN: I'm not saying this is fully explanatory. I'm bringing it out. This is one key feature where it seems like you need this feature because‚ books are a good example‚ if I preload hotel reviews where everything looks good, I'm never using trip advisor again because I went. This thing was supposed to be four and a half stars. It was a crappy hotel. The hedonic value is very important.

MYHRVOLD: Life insurance is the worst because you only find out when you die.

THALER: Mutual funds are really bad.

BEZOS: I don't care how sophisticated you are, you can't tell if you picked a good mutual fund.

MUSK: I don't think mutual funds are such a good example. If you look at someone like Vanguard, Vanguard has made huge inroads in mutual funds. It's killing everyone.

THALER: But they are not killing everyone.

MUSK: They're making huge inroads.

THALER: They're making huge inroads but they still have a small market share and a good example because‚ they're not as big as Fidelity‚ again this is a very illustrative example. Think of the battle between Vanguard and a high-cost provider. The high-cost guys advertise more. You have a market where the smart people go to Vanguard and the less sophisticated people go to the people whose ads they see.

MYHRVOLD: The choice architect here is saying you're unhappy with something where there is remaining choice. Until Vanguard got close to 100 percent, you would count that as not a success.

THALER: No. You're putting words in my mouth.

MUSK: Vanguard has also made the rest of the industry more honest and lowered their fees.

THALER: Absolutely. I'm a Vanguard user. I think they're great. But they don't have 100 percent market share. They have a five or 10 percent market share.

MUSK: But what is their change in market share relative to others?

THALER: In another 100,000 years.

MULLAINATHAN: Let me disagree. I'll be more aggressive than you are on this point. I don't think Vanguard in 10 years will have made the industry more honest. Let me articulate why.

MUSK: They have already made it more honest. But all right.

MULLAINATHAN: This will be a short one, a blip, and let me explain why.

When you can't evaluate things like how good your fund is after the fact, you are forced into evaluation before the fact on the basis of a set of heuristics. Vanguard has spread a good heuristic that makes sense given the current pricing of mutual funds: we have no load. It's clear what I would do if were Fidelity. I, too, would have a no-load fund. I would screw you over completely on some other dimension. This isn't fiction. Take the index fund. There was a great heuristic that was spread which was, buy index funds. What we had very shortly thereafter was the emergence of index funds with huge loads, which are now worse than taking actively managed funds. If you look at the modal index fund, it had this feature.

I'm pointing this example out because when we evaluate these products that we can't derive our hedonic value from after the fact, we're forced into heuristics and those heuristics may not have a settling norm. That is the challenge with these types of markets, which is that there is a way to look like that guy who tries to be honest but to be even more dishonest on some other dimension. There is this chasing pattern that can emerge. I'm not saying that is exactly what will happen but that's the underlying mechanism that one fears.

MUSK: Have these industry fees gone up or down or stayed the same. What's the trend?

THALER: Flat.

MUSK: Are you sure?

THALER: Yes. It's shocking. Twenty years ago I confidently predicted, as you would have, that fees have got to be trending down. No evidence for that. If anything, if you look at the big picture, fees have gone up because hedge funds have gotten a much bigger market share and they are charging two and 20. If you look at all the assets under management, the trend is up.

MUSK: Or is a correction occurring in hedge funds?

THALER: Well, from huge to not quite as huge, and for every Bear Sterns that crashes, there are 50 more that pop up.

This is a conversation that I would like to continue over the next day. In the meantime Sendhil is going to continue this in a slightly more structured way.

Sendhil Mullainathan

MULLAINATHAN: I want to pick up where the conversation was going. What I want to pick up on is this question about, when will competition erase these concerns and when will they not? I want to state my hypothesis up front. My hypothesis is that there is a set of goods for which competition will be unable to provide something that the consumer wants. This is the exact opposite of what we were talking about with shampoo. We were looking at the consumer and saying why do they want these two shampoos? Competition is going to provide what they want. Should it?

I'm saying something that is opposite. I'm saying that consumers want something that they are not able to get. What is that thing? That thing is simplicity. First I want to make this as an empirical statement and then we will try and dig in. And I'll be up front with you, at the one end we've got some empirical intuitive observations about the world. Way at the opposite extreme we've got some empirical observations about the psychology of individuals.

I'm going to try and hopefully together we can build is a bridge between these two sets of observations, or maybe we will see it doesn't build. But the observation at this end about the world is that, take cell phones. Ask anybody what he or she wants. They want a simple plan. They want to pick a plan where they understand what they are going to pay for and have it easily understood.

I'm going to take these two tenets as given. We can argue them if you would like, but intuitively there are a variety of things where people would like simple choice, an example being digital cameras. For the modal customer, they go in to a store, they look at the display of cameras and they ask themselves what is a megapixel, how am I suppose to choose this?

I want to say, there is a set of things where that doesn't appear to be happening. We can have one response to that. We can say it's because we are out of steady state. It'll take time. Market forces are going to come in. There will be aggregators. They are going to solve the problem. We have to wait. It's a little bit like you were saying, maybe we need to speed up the process, but it's going to get there. That's a very economist answer. In many senses, I am sympathetic to the idea that the market will be able to do it.

Let's put that argument on the side for a second. I want to explore a different argument. The argument is that the market can never get there. I want to see if that argument has some legs.

MYHRVOLD: You're going not to consider the possibility that simplicity is illusory. The customer says that they want it but given that the customer acts completely differently than what they say, you are going to take them at face value.

MULLAINATHAN: In fact, the core of my argument is going to be very related to what you just said, which is that the reason simplicity can't be provided is, I don't think the customer is lying to you. They genuinely want simplicity but I'm going to say that in fact it's not possible to define simplicity. That's the fundamental problem. That seems a little obscure right now but if you give me a moment I will get to that.

That doesn't get rid of the fact that people face real anguish. I'm not completely going in your direction. I am saying that when the customer goes to choose a digital camera or cell phone, it's painful. It is horribly disgusting. People avoid this task. Go and sit at a Best Buy. Watch how many people walk in, look at the digital cameras, spend 10 minutes, scratch their heads, pick it up, look at it, and then walk out. I'm not going to go all the way and say that they don't want this. I do think that they want it, but what I want to show you is the thing they want is hard to define and can't be.

THALER: One clarification: it's not that they want a simple camera.

MULLAINATHAN: No, no.

KAHNEMAN: They want a simple way to choose it.

MULLAINATHAN: Exactly. Let me be clear. They may want a horribly complicated camera. They want a way to see, I have these five, I know what this means. I'll give an example. Choosing an MP3 player. iPods are great. What do I choose? The color. The number of songs I want. The size. Great! That I understand. It's a fun choice. I get to choose on dimensions that make sense to me and I walk out of that experience feeling good.

Choosing a camera. What do I want? I want a camera that is light. I want a camera that takes different quality pictures. Depending on my preferences I may want something else. But when I go to look at the choice set of cameras, what the hell? I have a bunch of things I can't sort through.

Let me tell you a little bit about what we've learned from psychology that makes it hard to create this bridge. Maybe that will make more sense of what I mean by simplicity. The psychology I want to focus on‚one of the principles of choice that is absolutely essential. There is a theorem you can prove, and here is the theorem.

Suppose some products come with lots and lots of characteristics, millions of them, and suppose when looking at those characteristics you evaluate them. You look at megapixels and make an evaluation of what that is worth to you. Suppose you do that process, you use some map from the characteristics of the product to some perceived value of the product. If that is all that is going on, in a one shot game what the market will maximize is the perceived value. That's intuitive but it's important to keep that in mind. Markets maximize perceived value. If there is ex-post evaluability there will be room for a long run player who comes in and says I'm not going to maximize perceived value, I'm going to maximize ex post-perceived value because my customers will be happy and they will come back to me. But let me put that aside for a minute.

THALER: You can think about this in the context of what Danny Kahneman talked about last year in terms of experienced utility versus predicted utility. What Sendhil is saying is they have an incentive now to maximize now what you will think will be the utility of that product. What are the situations where that will coincide with the actual utility you will get from the experience with that product.

BEZOS: It requires a forecast.

THALER: Right.

MULLAINATHAN: It requires a forecast but what I'm pointing out is a pretty general and somewhat innocuous statement, which is that markets, absent repetition, will simply maximize perceived value. Why should they do anything else? It's like we said with shampoo. If you happen to like shampoo that says 'silk in a bottle', I'm going to produce shampoo that says 'silk in a bottle'. It's not my job to go hook up hedonometers and see if you are happier.

This is a simple frame up here. I have a perceived utility as a function of each product‚let's say the product is J‚as a function of the characteristics of that product. That seems like an intuitive model. We've used this implicitly in all of our conversations so far.

HILLIS: Where does brand come in?

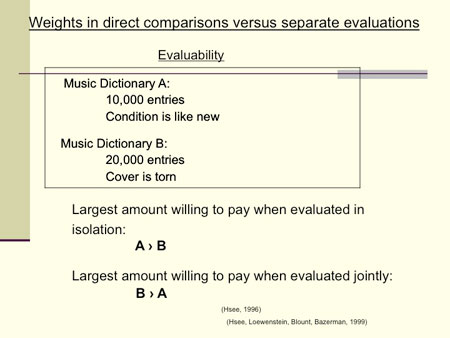

MULLAINATHAN: That's a characteristic. I can modify this model a lot and nothing much changes. Of I say I've got some forecast and I have some realized utility and some learning process that takes place, that's fine. I can allow that to take place. But there is something else that happens, which is outside of this‚this framework seems incredibly general and almost vacuous, it is so general. But despite being so general, it's missing one very important thing, and that is what I want to show you now, which is probably the key finding of psychology as far as markets are concerned. This is interesting work by Chris Hsee and his coauthors.

This will involve something that I'm sure is close to all of your hearts, music dictionaries. Chris Hsee and his coauthors showed people the following. Music dictionary A exists. It has 10,000 entries and its condition is like new. What would you pay for it? What would be the value you would place on it?

In this model, I don't know what 10,000 entries mean, I don't know what the condition 'like new' is, but I make my best guess. We can argue whether I made the right guess or the wrong guess and maybe over time I get it right but I make some guess. Then you ask people to evaluate music dictionary B. 20,000 entries. Cover is torn. Again, people make some guess, they look at these characteristics.

BEZOS: Are they doing these in isolation?

MULLAINATHAN: That's exactly it. They do this in isolation and they come up with a number. Then a third group is given both and told please put a number on music dictionary A and music dictionary B, what would you pay for this? Any guess as to what is going to happen?

MUSK: The same.

MULLAINATHAN: This model would suggest the same. I'm looking at these characteristics, I'm making a value. Why would it matter? Anyone want to make a guess?

MUSK: Well, wouldn't it matter whether they care if it's more comprehensive or in better condition? Are you saying it's the same individual?

MULLAINATHAN: No. I'm using randomization. Let's put one thing out that is very important. Random assignment allows us to guarantee that distributions will be the same. It's not the same person that is making both choices but it's randomization. I use a large enough sample to use the law of large numbers to guarantee stability.

MUSK: The used one will be worth less.

MULLAINATHAN: When will that be the case?

HILLIS: When they're together.

MULLAINATHAN: Wrong guess. It's intuitive when I walk you though it. When I evaluate these in isolation, A looks better than B. There is an intuition for that. Is 10,000 entries a lot for a music dictionary or few? I have no idea. Should a music dictionary have 100,000 entries? Should they have 500,000? I don't know. It's a characteristic that I find hard to value.

BEZOS: In isolation.

MULLAINATHAN: That is exactly the point. When viewed separately, in this model separately and jointly has no meaning, this thing looks better than this. Then put them next to each other. Do you want to be the moron who bought the 10,000-entry dictionary when there is a 20,000-entry dictionary? Why is it I'm making a big deal.

KAHNEMAN: You didn't emphasize the fact that it's very easy to know that when the cover is torn, that's bad.

MULLAINATHAN: Exactly.

KAHNEMAN: That is the contrast.

MULLAINATHAN: Let's write this out a little bit more carefully.

What we have is a utility now. We're evaluating torn cover, number of entries. We're not just evaluating these in isolation. Torn cover I can evaluate in isolation and jointly. I know what it means to have a torn cover. It will annoy me all the time that I just paid good money for a book that from day one has a torn cover. I can understand that. But this thing is something whose hedonic value I have no idea what it means. I start to impute it based on what else is in my choice set.

In other words there is another terms here‚ I'm going to put a "C"‚which is the choice set affects my translation from characteristics to perceived utility. Does that make sense? This model seems trivial but in fact it's missing something ultra important from the point of view of psychology.

Why does this little effect turns out to make a big, big difference? Before I tell you, let me show you a few more examples that are interesting.

This is a public policy example. The Department of Transportation is deciding between two roadway designs near a large American city. These are associated with two different types of auto accidents and consequently different rates of serious and minor injuries. They define what serious injury means and then these subjects are asked, in the blank below, please fill in the number of minor injuries.

Here people are asked to write in an indifference point. They say road design A has 15 major injuries; 1,525 minor injuries. And road design B has 11 serious injuries and a number here. What is the number of minor injuries that B should have to make you indifferent between A and B? That's the question that's asked.

Again, you will notice that this has the same feature of hedonic characteristics. You have to put some weight on minor injuries, some weight on major injuries, do that exchange rate and put a number on it. That's the problem. Again, maybe we grossly mis-value minor injuries. Maybe we under-, over evaluate, who knows? But there is a translation problem to put a number here. Obviously, what I'm going to show you is that if I give people a different choice‚so one group is shown this, and again random assignment, a random sample is shown this.

Same problem. All I have done is change the minor injuries associated with group A. I like to think of this as an exchange rate effect. I don't know what my trade off between major and minor injuries should be, so I use my choice set to infer the exchange rate. In the first one, I don't know, 1-100, that's pretty reasonable. In the second one, one-to-one looks reasonable.

What you find is—and you find this with a large sample of people—you get exchange rates here that are of the order of 26.3 and you can't read this but you get exchange rates here that are of the order of 2,000, which is the exchange rate problem. You find this, and this is the part that I love, most Elgar did this with a group at Brookings of senior policy makers. You find similar, 34 versus 2,000. He did this with a bunch of Federal Reserve Bank board of governor's guys, and you find the same exchange rate.

I'll give you an example of where this is super important. One thing that I found is that economists are terrible at thinking about finance, and you guys are probably going to be terrible at thinking about computers. Go with somebody who doesn't know anything about computers. Watch them shop for things like, how much would you pay for more hard disk space? You don't know what you should pay for that. But if I give you a choice set with two computers, Computer A 80 gigs, $1,500; Computer B, 100 gigs, $1,700. You infer that probably 20 gigs should be worth this much to me.

Then if I add computer C, which is off the regression line, it will look like a great deal. In effect, if I was creating a choice set, suppose I controlled your world, I can use this effect to add an element to that choice set, to then get you to infer an exchange rate and make one thing look cheap and one thing look expensive. That's an observation. I can show you a few more of these choice set things that are interesting if you guys will have some patience.

BEZOS: Please.

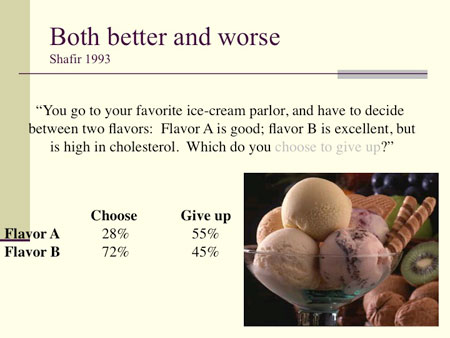

MULLAINATHAN: Here is another choice set which is particularly interesting.

MYHRVOLD: Or don't go to an ice cream parlor, for God's sake.

THALER: Give us a hard problem.

MYHRVOLD: But you've asked a different question and you get a different answer.

MULLAINATHAN: Agreed. I've asked a different question and I get a different answer. But notice this is interesting. This tells us something fundamental about choice sets. If I go to a choice set and I start eliminating alternatives until I end up with the one I like, I'll end up with a very different choice than if I go to a choice set, pick out the three I like most and then pick one from there. Why is that important? That tells us that the way in which the choice process funnels you dramatically affects it. This is a different thing.

HILLIS: "Would you like to decline the coverage?"

MULLAINATHAN: Yes. Exactly. But notice that it's not just an issue of the framing of declining a plan. That's what's important here; I'm not saying the path defaults.

BEZOS: It's path dependant.

MULLAINATHAN: It's path dependent on things that are more than just about defaults. This is where it gets very basic and why I wanted to push back on your point about simplicity. If you look at this, what value do you put on a person's utility? Do they value flavor B more than flavor A as it appears in this choice mode? Or do they value favor A more than flavor B? Let's assume we worked out the math that 30 percent of the people are being inconsistent across two modes. What value do we put on that? And why that is important is because in some sense the choice process is not just a choice process but it's a value construction process. I don't know which ice cream flavor I want and part of choice is constructing values.

BEZOS: Say it one more time, "part of choice is constructing value"?

MULLAINATHAN: Is constructing my value. That is, it's not that I enter into a situation with a fixed utility. The choice process and the choice set‚. I derive my value from that choice set, from that choice process.

HILLIS: It's kind of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle.

MULLAINATHAN: That's exactly right. That's going to be the core of the problem, as I hope you see why it is we have a strong intuition that this problem here is going to lead to dramatic failures over here. The reason for that is in all of these examples, I'm constructing the choice set. I have you in front of me and I'm putting the three elements in front of you and I'm playing with it.

The market doesn't have that luxury. There is not one person constructing your choice set. The market is coming in to construct your choice set. What that means practically is that if I put out torn cover, number of entries, and some other guy puts out more entries, what happens now? Well, his product may look more attractive. But notice something else is happening. Your product now looks less attractive. Not in relative terms. It's not that his product looks better than your product. He's imposing a genuine externality on you because he is changing the valuation process.

When Vanguard comes in and says I am going to be a no-fee fund, they are not just making a value statement. They are changing the underlying value construction process and thereby changing the entire market because now everybody needs to respond to that value construction process. The question we have to ask ourselves is, will those changes be always towards the better?

MUSK: Mostly.

MULLAINATHAN: Will it be mostly? When will it not be? Obviously as an economist I think markets work a whole lot of times. I don't think that should be called into question. What I'm trying to understand is, when might they fail? This is a different kind of market failure than we are used to. This is a market failure that is arising because we are increasingly dealing with products in the world.

BEZOS: Connect the dots for me. How do get from here to the set of circumstances where it might fail?

MULLAINATHAN: I'm going too fast. Let me give you a few more examples of this. These are a few examples of real products where this happens. I will do this with anecdotes because it is easier.

I have a niece who I really like and my dad who is really crazy. My sister said she moved my niece to a better school district. I said, 'Great. I'm really glad.' In my family these are not things that people usually do. I'm glad that somebody is doing it. I said, 'This is great.' My dad calls me up and predictably he is contrarian. He says, 'What a stupid idea.' Predictably I say my dad's an idiot.

MYHRVOLD: Yet you're a paternalist.

MULLAINATHAN: No, I'm not. Notice I haven't said anything paternalistic so far. I don't necessarily believe in anything paternalistic. I'm trying to build a story. Then, this is going to be a long conversation, so I might as well ask him, why do you think it's a bad idea?

Then he said something genuinely brilliant. He said, Look I know that the school she is moving to has two more test score points on the average test score scale. I said yes, it's good. He said, yes, it's the number one school, whereas the school she is in now is number five. I said, yes that's right. Then he said, but you agree with me that she is losing her friends and she is going through a tough time. I said, yes but she is gaining something. Then he said to me, what are two test point scores worth?

It's like the number of entries in a music dictionary. Is two test score points a whole lot? Is it a tiny, insignificant difference? I'm not saying he's right. I realized very quickly how I was in a little bit the same as the Chris Hsee's situation with test scores. I'm forced to make a choice on a characteristic whose value has no meaning for me. It's test score points.

If I did a lot of research and I went into it I might be able to figure out that data shows us that two test score points in middle school is worth X percent probably of getting into an Ivy League school, or something. Maybe that data is out there. But certainly I couldn't find it. That is one example of a tell tale sign of when we might be hitting this problem.

I want to be honest with you, we don't have the full bridge built. I'm trying to draw for you what might be the elements of the problem. One element of the problem is, when there are characteristics that have no hedonic value and I'm forced to use the choice set to impute hedonic value to it. To make my dad's problem very clear, I don't even know what the scale of that was. If every school district had gone down from 80 to 40, I still would be using a relative thing. You wouldn't be saying oh my God we're down to 40.

PARKER: This is an example where the two test scores points are probably a proxy for a lot of other things.

MULLAINATHAN: Exactly.

PARKER: What you are doing is you are putting your kids in a school where a bunch of other people who think like you put their kids in a school, which means that maybe your kids are less likely to get in trouble because all of these parents are equally neurotic.

MULLAINATHAN: Good point. It's a great story, which will allow me in this particular example to get out a value in the two test score points. The story is, I know the best parents go to number one. I want to be where the best parents are. Who cares what number one is, I'm going there. I think that is totally true and it is plausible in this example.

Where it gets more complicated is a large majority of parents face a choice, and school choice is becoming big, face a choice between number 10‚ you're in the inner city, you are a black family, you're in a crappy school district‚ you have to make a choice. Number one is pretty far away, it might not be possible for your kid to get in; you can send your kid to number six, but it's got a 30-minute bus ride. Is that worth it? How much value should I put on it?

I'm not saying people are making a mistake. Don't get me wrong. I'm pointing out there is a hedonic valuation problem, which is that you have U: Xi, but that the choice set and the choice process are going to play a role in the construction of the values of that index. That is all I'm saying. I'm not trying to say they are making a mistake. I'm saying what the structure is of this problem.

MYHRVOLD: This is going to sound impossibly rude and I don't mean that but are we supposed to be surprised? You're talking like there must be a constituency that you say this to that is up in arms at this point.

MULLAINATHAN: The reason we should be surprised is the following, which is this story is so intuitive, so obvious. It's beyond trivial. I agree with you 100 percent. On the other hand when I wrote up that first formula, "U: X1 -> XK", you were pretty on board with that formula. I'm not saying that you should be surprised in the sense‚ this story has no surprising elements to it, test scores are hard to evaluate.

BEZOS: The example with the serious injuries versus the minor injuries. I found that very surprising. For me it's like a mental trap that is easy to fall into. That exchange rate that you impute from scenario A.

KAHNEMAN: I don't understand your objection. This is a Socratic exercise. You're not surprised because now you understand it. But the point that is made is that you didn't see it, so it's one of those things that become obvious only when you point it out. You could have the whole world ignoring it, and that's the point.

MULLAINATHAN: That's a good way of putting it. That is what I take away from it. These studies are not even mine.

BEZOS: Plus even after you see the point you are still susceptible to the flaw.

MULLAINATHAN: That's exactly it.

BEZOS: I'm sure the next time I'm presented with such a situation, I'm going to instinctively make the mistake you taught me to be careful of.

KAHNEMAN: And you may not know it.

THALER: The problem is you will only see if it was highlighted.

KAHNEMAN: The problem is worse; you won't know when you are in that situation, because basically most of the time we choose things one at a time, and so we have no idea how we would choose if the choice set was different. The world is a one-at-a-time thing.

ROMER: The interesting thing is if you figure this out how might it change your business plan because you might start competing strategically on changing what is in the choice sets in ways that help you as a business but might end up making the consumers all worse off.

MULLAINATHAN: Potentially.

MYHRVOLD: What I would argue is that lots of folks already do but they might not know exactly that they are doing it.

ROMER: The consequences of competition when you have, say, fixed choice sets might be very different from competition when you can manipulate the choice sets, even may be worse off for all the firms and the consumers.

MULLAINATHAN: I want to point to something Danny Kahneman said to reinforce it. There is one thing about these experiments that make them look—I want to show you this but I can't—that make them look less surprising than they are is that we have the bird's eye advantage of seeing people in two different choice sets. In our lives we inhabit a choice set. That is why it is often hard for us to intuit how powerful the impact that choice set was on our value constructions. That is the benefit of moving to this. This goes back to randomization, doing this between sets.

KAHNEMAN: It's completely general. Its framing effects are not, though. You're in a frame and you don't imagine alternative frames. Everybody knows this but it does create a problem.

MYHRVOLD: What it does is it says you should have a checklist. By the way, are you aware of the frame of reference that you're in? If you have such a checklist, it forces you to think.

KAHNEMAN: If you knew what the alternatives were.

THALER: Yes. And if had the rest of your life to decide what to have for lunch.

MUSK: The dictionary example and the road accident example, I don't think were very good real world examples because if you were asked right now, if you went and Googled it or let's say the book example, let's say you're looking at Amazon or Ebay used books, you may immediately see some value number for number of entries or condition of book and you would be able to choose, what do you care about, and get that information very quickly. The same applies for the road accidents. You could Google, what is the road accident rate and then you are going to have much better context and expectations.

PARKER: I will say additionally they are not particularly real great examples, good real-world examples, because you don't know who the actual market for a music book is going to be people who perhaps know that market better than anybody in this room and maybe the important selection criteria has nothing to do with either of those two factors and they probably don't.

MULLAINATHAN: Let me push back and I want to argue that they are very important examples exactly for the reasons you get said. Take the digital cameras.

A lot of times when we construct these experiments they are nice because they distill a feature of a real world example, and that is the whole point of a good experiment. It shouldn't be too good of an example on its own. It should allow us to see a feature. What the music dictionary says to me is like I have no clue what 10,000 entries is or 20,000 entries is.

MUSK: Then why buy a music dictionary?

MULLAINATHAN: Well, take digital cameras. I have no clue what a megapixel is but I want a digital camera. In a way it is true that there are many examples where I do purchase and there are characteristics that I have no clue what they are and you are right a music dictionary is not a great example because you could say what an obscure thing. Most people won't buy it.

MUSK: It's that if you're going to buy it. Unless you are going to run into some used bookstores, you're probably going to buy it online, you would see a bunch of other music dictionaries. You would have to know something about music or you wouldn't care about music dictionaries.

KAHNEMAN: Let me sharpen the psychological point here that there are evaluations that you can make one attribute at a time, so that you know when you see torn you know it's bad. That's it. You don't need a comparison to know that torn is bad. That is a very broad problem.

MYHRVOLD: Sure. But Elon's point is, the point of an experiment is to cleverly put people in a weird situation, that is artificial, to measure something, and that is to say, how do we make a decision when we have not enough information, explicitly not enough? The answer is we go and we impute some exchange rate, as you say.

MULLAINATHAN: Which the choice set gives us.

MYHRVOLD: Which is choice set dependent

MULLAINATHAN: That's the key point. That is essential.

MYHRVOLD: But it's a little bit like saying, ok suppose you have to make a Bayesian inference and you have no idea as to the priors. You say I have no idea.

MUSK: You've got to have something.

MULLAINATHAN: No. You guys are trying to build a bridge too fast.

PARKER: There are a couple of other factors here. Price is extremely relevant. Jeff made his point because the higher the price or the more aggregate decision-making power exists, which is essentially the same thing, the more likely you are to spend time evaluating various different options. Price factors are more important in this model than it is being made out to be.

Then there are counter examples. Apple understands exactly all of this and they recognize that people can't make decisions because they don't have the right evaluative framework. They literally put a different product at every known price point all the way up the chain and then price becomes the only significant decision-making factor. They have an iPod at $100, one at $150 and one at $200, one at $250 and one at $300. You literally spend the maximum amount of money that you can.

MULLAINATHAN: Maybe I'm misspeaking.

KAHNEMAN: You can be seriously manipulated in that way because they are setting it up by their costs. In terms of that, you could set up that list so as to maximize your profit.

MYHRVOLD: That's what they do.

KAHNEMAN: This process is what they do and the point that is being made is this is not maximizing the utility. There is no way for the consumer to know.

MULLAINATHAN: That's exactly the point. The mistake we are making here is I do want to build this bridge one step at a time and you guys are forcing me to say, I've shown you music dictionaries, therefore we are already here. I don't think we are already here. What we have shown is one of the conditions that seems very important. It doesn't solve the problem in itself. In here I'm showing that I decide the valuation based on the choice set. But you are pointing out that maybe I can define valuation in other ways. I can do a search, I can ask friends, and maybe I can compute value in other ways. I'm not saying that won't happen. I'm pointing it out.

MYHRVOLD: People like it better if you give them more information.

MUSK: Absolutely. You're measuring the error, a population error. For any given question with a given set of data, what errors bars are you going to get?

BEZOS: For example, Elon's point, if you had taken that serious injury/minor injury thing, if you had added to that exercise, I wonder what would happen if you said, here is how much hospitalization costs for a major injury and here is how much hospitalization costs for a minor injury.

KAMANGAR: There are a lot of things that you can't do that for. There are things that involve your own preferences. For example, it's the Wall Street Journal, where they have a pricing plan, where you can buy Internet for $50, or you can buy print for $100, or print and Internet for $100. The percentage of people who take the combined option changes dramatically if that third option is offered. There you can't measure what your utility is for having both. You can have extra utility that helps you decide that.

MULLAINATHAN: That is a key point because in a way that makes the music dictionary examples better than the minor injuries/major injuries.

BEZOS: There is no way to quantify it.

MULLAINATHAN: Yes. You're trying to do your own hedonic valuation, it is what you are trying to figure out, but I'm forced to draw from other situations to make that inference.

BEZOS: Even for something simple, it's like I don't know what my favorite color is until you give me some other choices.

THALER: We need to break for lunch. We will continue this conversation at our tables.