Edge in the News: 2010

Michael Shermer, the libertarian-leaning skeptic and critical thinker who is as formidable and illustrious as he is implacable and indefatigable, lets his hair down in a paean to Bill Gates that is so fulsome I suspect it's a joke.

Describing a TED-related dinner organized last week in Long Beach by John Brockman, Shermer describes how the multibillionaire Microsoft founder wowed everybody at his table. (Imagine a man so brilliant he makes John Cusack seem like a minor league penseur by comparison.)

Describing a TED-related dinner organized last week in Long Beach by John Brockman, Shermer describes how the multibillionaire Microsoft founder wowed everybody at his table. (Imagine a man so brilliant he makes John Cusack seem like a minor league penseur by comparison.)

I understand -- believe me I really understand -- how wealth or success or hotness can make even the most trivial expulsions seem like nuggets of pangalactic genius. But while Gates' pronouncements on the economy offer something to please enemies of the ARRA stimulus package and plenty to infuriate enemies of the bank bailout, what unites his comments is their sheer heard-it-a-million-times-before banality:

I asked Gates “Isn’t it a myth that some companies are ‘too big to fail’? What would have happened if the government just let AIG and the others collapse.” Gates’ answer: “Apocalypse.” He then expanded on that, explaining that after talking to his “good friend Warren” (Buffet), he came to the conclusion that the consequences down the line of not bailing out these giant banks would have left the entire world economy in tatters.

Arianna Huffington asked Gates about Obama’s various jobs programs to stimulate the economy. Gates answered: “Let me tell you about what leads companies to create more jobs: demand for their products. My friend Warren owns the world’s largest carpet manufacturing company. Their business has dried up because the demand for carpets has declined dramatically due to the drop off in the construction of new homes and office buildings. If you want to create more jobs you need to create more demand for products that the jobs are created to fulfill. You can’t just make up jobs without a real demand for them.” I believe that was the last thing Arianna said for the evening.

This led me to ask Gates this: “If the market is so good at determining jobs and wages and prices, why not let the market determine the price of money? Why do we need the Fed?” Gates responded: “You sound like Ron Paul! We need the Fed to steer the economy away from extremes of inflation and deflation.” He then schooled us with a mini-lecture on the history of economics (again, probably gleaned from Timothy Taylor’s marvelous course for the Teaching Company on the economy history of the United States) to demonstrate what happens when fluctuations in the price of money (interest rates, etc) swing too wildly. I believe that was the last question I asked Gates for the evening!

It's like that acid trip where you were just centimeters away from figuring out the whole universe! As noted above, I suspect this is all just a wheeze by Shermer, and if so I apologize for stepping on his joke. But in the interest of everybody who thinks Planet Earth would have survived if Goldman Sachs had been allowed to go out of business (and for reasons I'm happy to go into at greater length, Goldman Sachs would not have gone out of business even under the worst-case scenario), I'd like to point out something to Bill Gates:

It's 2010 now. If you're still trying to justify Hank Paulson's miserable experiment in lemon socialism, you're gonna need more synonyms for "apocalypse," "chaos," "meltdown" and "armageddon." They're definitely out there: I looked them up using Microsoft Word's thesaurus function.

Ladies and gentlemen, Chauncey Gardiner:

Some people whose names you may know or computers you may have used all had dinner together last week.

Photo above: Apocalyptic shit-disturber John Cusack eats the final grape at the namedrop alpha table, drawing heated commentary from Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates, who sources say did not get a single grape.

(L-R, for reals, EDGE 2010 dinner: Jared Cohen, US State Department; Dave Morin, Facebook; John Cusack, actor/writer/director/thinker; Dean Kamen, Inventor, Deka Research; Bill Gates, Microsoft, Gates Foundation; Arianna Huffington, The Huffington Post; Michael Shermer, Skeptic Magazine. Not shown in this photo, but huddled around the same table, were Peter Diamandis, George Church, and me. )

Here's the photo gallery for this dinner, hosted by John Brockman and EDGE to herald "the Dawing of the Age of Biology." Let the jpeg record show that I managed to get up close and personal withMarissa Mayer and Nathan Wolfe, then later with Danny Hillis.

More about the big ideas discussed, after the jump.

John Brockman, in presenting the theme for this 2010 edition of the annual EDGE dinner, wrote:

In the summer of 2009, in a talk at the Bristol (UK) Festival of Ideas, physicist Freeman Dyson articulated a vision for the future. He referenced The Age Of Wonder, by Richard Holmes, in which the first Romantic Age described by Holmes was centered on chemistry and poetry, while Dyson pointed out that this new age is dominated by computational biology. Its leaders, he noted, include "biology wizards" Kary Mullis, Craig Venter, medical engineer Dean Kamen; and "computer wizards" Larry Page and Sergey Brin, and Charles Simonyi. He pointed out that the nexus for this intellectual activity — the Lunar Society for the 21st century — is centered around the activities of Edge.

All the scientists mentioned above by Dyson (with the exception of Simonyi) were present at the dinner. Others guests who are playing "a significant role in this new age of wonder through their scientific research, enlightened philanthropy, and entrepreneurial initiative" included Larry Brilliant,George Church, Bill Gates, Danny Hillis, Nathan Myhrvold, Jeff Skoll, and Nathan Wolfe.

Ve lo ricordate il proverbiale stereotipo dello scienziato svitato, con la testa fra le nuvole, arroccato nel suo laboratorio alle prese con formule misteriose? Bene, ha fatto anch’esso la fine delle cabine del telefono o dei videoregistratori, definitivamente disperso nel tempestoso oceano del mutamento. Fino a ieri disciplina austera, fredda e lontana, ora con una travolgente metamorfosi la scienza si è imprevedibilmente fatta pop, è diventata calda e comunicativa, si è venuta umanizzando.

Ve lo ricordate il proverbiale stereotipo dell’atleta forte bello e imbecille e del nerd geniale ma inguardabile e snobbato dalle ragazze? Ecco, se ve lo ricordate questo è il momento di scordarvelo. Quello che da più parti è stato proclamato il nuovo Einstein è un ragazzone californiano che si chiama Garrett Lisi e che ha scritto la sua “eccezionalmente semplice teoria del tutto” destinata a mutare per sempre i paradigmi della fisica non in biblioteca o in accademia ma sulle spiagge dove vive facendo surf. C’è un nuovo prototipo di scienziato che non soltanto non si sottrae alle lusinghe del mondo - almeno non a quelle più appassionanti - ma anzi se ne serve per nutrire ed allargare la propria ricerca.

Se vi avventurate fra le conferenze video di Ted, vero e proprio brain trust dell’innovazione, se vi tuffate in quella inesauribile sorgente di idee che sono i libri molteplici e corali curati da John Brockman (in particolare Scienza, next generation), non avrete più dubbi: la scienza non soltanto si è impossessata del dibattito filosofico, ma sta riscrivendo le mappe del nostro immaginario. C’è nella scienza una forza comunicativa ed energetica che non ne vuole più sapere di stare dentro i vecchi confini e le vecchie categorie.

In questa nostra epoca, biologia, genetica, chimica, fisica si stanno allargando in tutte le direzioni, in una lussureggiante varietà di nuovi saperi, e questo è il segno inequivocabile che la scienza sta vivendo una fase assolutamente espansiva ed evolutiva. Senza più specialismi autoreferenziali, senza più mediazioni, la ricerca scientifica sta mettendo al centro di se stessa e della nostra sensibilità la questione dell’estensione dell’esistenza umana. Della nostra vita sta evidenziando non più soltanto i limiti - come epressivamente fanno tutti i sistemi di pensiero convenzionali - ma innanzitutto le risorse, la potenza. Ci sarà molto da divertirci, credetemi.

Having spent many a column espousing the wonders of the internet, my final column will sound a warning on the dangers.

The first is anonymity. This can be a curse and a blessing online. Sites such as Wikileaks – which desperately needs funding to stay open – provide a valuable place where information can be put into the public domain anonymously.

But there is a flip side. Glance at the comments below any newspaper opinion article and you will be given a whirlwind tour of the most unpleasant aspects of the public psyche.

You don’t overhear conversations such as this in the pub or at work. It’s the anonymity that provides people with the cover to get away with such language without being hit in the face.

And it’s the anonymity the internet provides that allows authoritarian regimes to spy on businesses without the state being held responsible.

It allows criminals to perpetrate scams online that cost the public billions of pounds a year, and illegal downloaders to ply their craft without fear of apprehension.

One of the original, long-abandoned arguments for ID cards was that they could provide a person with a secure online identity, so when you logged on to your bank’s web site, for example, you could prove your identity. If people were more accountable for their online interactions, they might be more civil – and law abiding.

But the internet carries an arguably more pervasive and long-term danger than the provision of anonymity and that is the way that it changes and shapes thinking and the way people interact with information.

The online forum edge.org recently tackled this problem. It asked leading scientists, technologists and thinkers: How is the internet changing the way you think? A number of people, including American writer Nicholas Carr and science historian George Dyson, outlined fears that the web is at risk of reducing serious thought rather than promoting it.

One argument posits that a more democratic approach – with everything posted online attributed an equal weight, whether right or wrong – encourages a cavalier attitude to the truth.

Another is that collecting information online reduces our attention span. We will scan a Wikipedia article on a subject, rather than read a book about it.

Furthermore, it is harder to distinguish between the relative value of sources online. Whereas in real life we would trust a professor more than a eight-year-old, online those boundaries are blurred by a lack of clear distinction between sources – both people would be able to type a comment on a site, and we have no way of knowing who they are, other than their words.

The “trust distinguishers” we use in the physical world are easier to fake online. Whereas a professor offline could be examined for reliability by his age, manner of speaking and so on, these things are easier to disguise on the web.

In many ways the internet represents many of the same problems as a democracy. By giving an equal voice to all, it empowers many of those who are disenfranchised economically or socially and who would not otherwise be heard.

But at the same time, it gives an equal voice to the extremities of society – making it easier for those who run extremist jihadi sites, or sites that deny the holocaust, to spread information.

Just as in real life, nobody should be denied freedom of speech online. The internet can and must be accessible to everyone. But we need to develop and teach new ways in which to distinguish between, and prioritise, information that we find online if we are to retain our notions of what is correct and incorrect.

Do you remember the proverbial stereotype of the scientist screwed with his head in the clouds, perched in his laboratory dealing with mysterious formulas? Well, he did also the end of the phone booths or video recorders, definitely missing in the stormy ocean of change. Until yesterday discipline austere, cold and distant, now with a sweeping metamorphosis science has made pop unexpectedly, has become warm and communicative, he came humanizing.

Do you remember the proverbial stereotype of the athlete looking strong and stupid and brilliant nerd but unwatchable and snubbed by girls?Well, if you remember this is the time to forget it. What, there have been proclaimed the new Einstein is a California boy named Garrett Lisi and who wrote his "exceptionally simple theory of everything" destined to change forever the paradigms of physics at the library or in the academy but surfing beaches where he lives. There is a new prototype of a scientist who not only does not avoid the lure of the world - at least not to the most exciting - but instead uses it to nourish and expand its research.

If you do venture between the conference video of Ted, a real brain trust of innovation, if you dive into that inexhaustible source of ideas that are multiple and choral books edited by John Brockman (particularly Science, next generation) will not have no doubt: science not only has taken possession of the philosophical debate, but is rewriting the map of our imagination. There is a force in science communication and energy that does not want to know more to stay within the old boundaries and the old categories.

In this modern age, biology, genetics, chemistry, physics are increasing in all directions, in a lush variety of new knowledge, and this is an unequivocal sign that science is experiencing a very expansive and evolutionary. No more self-specialisms, without mediation, scientific research is putting itself at the center of our feeling and the question of human existence. Of our life is not just pointing out the limits - such as send an explicit form all the conventional systems of thought - but above all the resources, power. There will be much fun, believe me.

di ALDO FORBICE

La casualità regola la nostra vita anche se la grande maggioranza degli esseri umani non ne è convinta. Lo hanno sempre affermato gli scienziati. Chi dedica un saggio a questo tema, tutt'altro che marginale, è Leonard Mlodinow, La passeggiata dell'ubriaco (Rizzoli). L'autore, che dopo il dottorato conseguito a Berkeley, insegna all'Università di Caltech, sostiene che la casualità ci insegue per tutta la vita: dalle aule dei tribunali ai tavoli della roulette, dai quiz televisivi, al destino degli ebrei nel ghetto di Varsavia. Ogni evento della storia e delle nostre vite è segnato dal caso. Eppure la maggioranza delle persone pensa che il destino sia «segnato» da Dio o da altre autorità sovrannaturali. Per dimostrare la casualità di ogni evento l'autore racconta numerose storie di casualità. Eccone una fra la le tante: un aspirante attore lavorava per vivere in un bar a Manhattan, per diversi anni è stato costretto a dormire in una topaia, riuscendo a fare qualche comparsata negli spot televisivi. Poi, un giorno d'estate del 1984 andò a Los Angeles per assistere alle Olimpiadi e per caso incontrò un agente che gli propose un provino per un telefilm. Lo fece e ottenne il ruolo. Quell'attore si chiama Bruce Willis; così iniziò la sua carriera.

Il fisico Mlodinow, con il suo libro, ci fa compiere un viaggio affascinante nel mondo della casualità e della probabilità, restituendoci certezze e facendoci riflettere sulle nostre scelte, giuste o sbagliate che si siano rivelate. Si è trattato però di decisioni nostre, dettate dagli eventi casuali, e non certo preordinate o decise da fantasmi o da esseri sovrannaturali. In altre parole, «le leggi scientifiche del caso» esistono. Magari sono le stesse che i più, per ignoranza, per pigrizia mentale o solo per autoassolversi da errori commessi, continuano a definire «fortuna». Ma il futuro ha una direzione per ognuno di noi? Non interpelliamo maghi, fattucchiere od «oroscopari», ma scienziati. Lo ha fatto Max Brockman, un agente letterario che si occupa di divulgazione scientifica: ha invitato 18 giovani scienziati a scrivere altrettanti saggi che ora sono stati raccolti in un libro, Scienza. Next Generation (il Saggiatore). Questi giovani studiosi cercano di dare risposte a domande come queste: che direzione vogliamo dare al futuro?, che cosa sta cercando di dirci l'universo?, come possiamo migliorare gli esseri umani?, quanto è importante l'immaginazione?, l'homo sapiens è destinato a estinguersi?, e così via. Le risposte tengono conto dei dati e delle conoscenze scientifiche, cercando di interpretare le grandi linee della scienza che verrà.

«Il cielo stellato sopra di me, e la legge morale dentro di me», ha scritto il grande filosofo Immanuel Kant. A questa massima si rifà il fisico Andrea Frosa (insegna fisica generale all'Università «La Sapienza» di Roma), che ha scritto Il Cosmo e il Buondio-Dialogo su astronomia, evoluzione e mito (Bur-Rizzoli). L'autore immagina che la Terra stia per essere colpita da un cataclisma naturale e l'Onnipotente decida di occuparsi dell'umanità che per lui «rappresenta una insignificante briciola di un cosmo infinito e multiforme». Consulta quindi i grandi pensatori di tutti i tempi (da Pitagora a Newton, da Democrito a Galileo e Laplace, da Aristarco a Einstein e Hubble, da Aristotele a Darwin, oltre ad alcuni scienziati viventi) invitandoli ad aiutarlo. L'autore, a 400 anni dalle scoperte di Galileo e Keplero, racconta in questo modo l'affascinante avventura millenaria sulle grandi questioni dell'universo, senza mai cessare di interrogare la ragione sulle nostre origini e il nostro destino. Di scienza, com'è noto, si occupano anche i filosofi. Lo fa anche Ernesto Paolozzi (docente di filosofia contemporanea all'Università di Napoli) col saggio La bioetica, per decidere della nostra vita (Christan Marinotti edizioni).

La moderna bioetica dà risposte sulla vita, la morte e la qualità della vita, invadendo i campi della filosofia, della scienza, del diritto e della religione. L'autore cerca di fare chiarezza su una materia complessa, al centro di dibattiti e infuocate polemiche, cercando di ricondurre la bioetica allo spirito originale del suo fondatore, V.R.Potter, che la considerava, come oggi Edgar Morin, «un ponte verso il futuro», cioè la disciplina che pone al centro del proprio interesse il destino della Terra, di tutta la biosfera. Un tema questo, sicuramente affascinante, di cui si discuterà (e si polemizzerà) ancora a lungo, ma che fa parte integrante del futuro dell'umanità.

The title of the book "153 reasons to be optimistic" (The Assayer) attracts at a time like ours, studded with worrying news of all kinds. But even more intriguing if one also reads the caption: "The great challenge of research." What promises? The question arises. The reasons are the answers gathered by John Brockman curator of 'work by many scientists working on the frontiers of science more extreme. Which I identify why, from their point of view and work, it is right to look positively at the future. A scientist must be an optimist by definition driven by 'enthusiasm to conquer something new. And the prospect to whom he dedicates his life is destined to bring the innovations that improve the lives of us all. The succession of short answers, but the content is impressive because he hears from the genome mapper Craig Venter (pictured) to Marvin Minsky that deals with immortality, by physicist Lee Smolin and Martin Rees on the energy challenge, by Freeman Dyson George Nobel Smoot. Many issues relate to general culture and society. All agree on one point: to show that the reason for optimism is absolutely true.(G. Ch.) REPRODUCTION RESERVED

Giovanni Caprara

"Comment l’internet transforme-t-il la façon dont vous pensez ?", telle était la grande question annuelle posée par la revue The Edge à quelque 170 experts, scientifiques, artistes et penseurs. Difficile d’en faire une synthèse, tant les contributions sont multiples et variées et souvent passionnantes. Que les répondants soient fans ou critiques de la révolution des technologies de l’information, en tout cas, il est clair qu’Internet ne laisse personne indifférent.

L’INTERNET CHANGE LA FAÇON DONT ON VIT L’EXPÉRIENCE

Pour les artistes Eric Fischl et April Gornik, l’Internet a changé la façon dont ils posent leur regard sur le monde. "Pour des artistes, la vue est essentielle à la pensée. Elle organise l’information et permet de développer des pensées et des sentiments. La vue c’est la manière dont on se connecte." Pour eux, le changement repose surtout sur les images et l’information visuelle ou plus précisément sur la perte de différenciation entre les matériaux et le processus : toutes les informations d’ordres visuelles, quelles qu’elles soient, se ressemblent. L’information visuelle se base désormais sur des images isolées qui créent une fausse illusion de la connaissance et de l’expérience.

"Comme le montrait John Berger, la nature de la photographie est un objet de mémoire qui nous permet d’oublier. Peut-être peut-on dire quelque chose de similaire à propos de l’internet. En ce qui concerne l’art, l’internet étend le réseau de reproduction qui remplace la façon dont on fait l’expérience de quelque chose. Il remplace l’expérience par le fac-similé."

Le jugement de Brian Eno, le producteur, est assez proche. "Je note que l’idée de l’expert a changé. Un expert a longtemps été quelqu’un qui avait accès à certaines informations. Désormais, depuis que tant d’information est disponible à tous, l’expert est devenu quelqu’un doté d’un meilleur sens d’interprétation. Le jugement a remplacé l’accès." Pour lui également, l’internet a transformé notre rapport à l’expérience authentique (l’expérience singulière dont on profite sans médiation). "Je remarque que plus d’attention est donnée par les créateurs aux aspects de leurs travaux qui ne peuvent pas être dupliqués. L’authentique a remplacé le reproductible."

Pour Linda Stone : "Plus je l’ai appréciée et connue, plus évident a été le contraste, plus intense a été la tension entre la vie physique et la vie virtuelle. L’internet m’a volé mon corps qui est devenu une forme inerte courbée devant un écran lumineux. Mes sens s’engourdissaient à mesure que mon esprit avide fusionnait avec le cerveau global". Un contraste qui a ramené Linda Stone à mieux apprécier les plaisirs du monde physique. "Je passe maintenant avec plus de détermination entre chacun de ces mondes, choisissant l’un, puis l’autre, ne cédant à aucun."

LE POUVOIR DE LA CONVERSATION

Pour la philosophe Gloria Origgi (blog), chercheuse à l’Institut Nicod à Paris :l’internet révèle le pouvoir de la conversation, à l’image de ces innombrables échanges par mails qui ont envahi nos existences. L’occasion pour la philosophe de rappeler combien le dialogue permet de penser et construire des connaissances. "Quelle est la différence entre l’état contemplatif que nous avons devant une page blanche et les échanges excités que nous avons par l’intermédiaire de Gmail ou Skype avec un collègue qui vit dans une autre partie du monde ?" Très peu, répond la chercheuse. Les articles et les livres que l’on publie sont des conversations au ralenti. "L’internet nous permet de penser et d’écrire d’une manière beaucoup plus naturelle que celle imposée par la tradition de la culture de l’écrit : la dimension dialogique de notre réflexion est maintenant renforcée par des échanges continus et liquides". Reste que nous avons souvent le sentiment, coupable, de gaspiller notre temps dans ces échanges, sauf à nous "engager dans des conversations intéressantes et bien articulées". C’est à nous de faire un usage responsable de nos compétences en conversation. "Je vois cela comme une amélioration de notre façon d’extérioriser notre façon de penser : une façon beaucoup plus naturelle d’être intelligent dans un monde social."

Pour Yochaï Benkler, professeur à Harvard et auteur de la Puissance des réseaux, le rôle de la conversation est essentiel. A priori, s’interroge le savant, l’internet n’a pas changé la manière dont notre cerveau accomplit certaines opérations. Mais en sommes-nous bien sûr ? Peut-être utilisons-nous moins des processus impliqués dans la mémoire à long terme ou ceux utilisés dans les routines quotidiennes, qui longtemps nous ont permis de mémoriser le savoir…

Mais n’étant pas un spécialiste du cerveau, Benkler préfère de beaucoup regarder "comment l’internet change la façon dont on pense le monde". Et là, force est de constater que l’internet, en nous connectant plus facilement à plus de personnes, permet d’accéder à de nouveaux niveaux de proximité ou d’éloignement selon des critères géographiques, sociaux, organisationnels ou institutionnels. Internet ajoute à cette transformation sociale un contexte "qui capte la transcription d’un très grand nombre de nos conversations", les rendant plus lisibles qu’elles ne l’étaient par le passé. Si nous interprétons la pensée comme un processus plus dialogique et dialectique que le cogito de Descartes, l’internet permet de nous parler en nous éloignant des cercles sociaux, géographiques et organisationnels qui pesaient sur nous et nous brancher sur de tout autres conversations que celles auxquelles on pouvait accéder jusqu’alors.

"Penser avec ces nouvelles capacités nécessite à la fois un nouveau type d’ouverture d’esprit, et une nouvelle forme de scepticisme", conclut-il. L’internet exige donc que nous prenions la posture du savant, celle du journaliste d’investigation et celle du critique des médias.

MONDIALISATION INTELLECTUELLE

Pour le neuroscientifique français, Stanislas Dehaene, auteur des Neurones de la lecture, l’internet est en train de révolutionner notre accès au savoir et plus encore notre notion du temps. Avec l’internet, les questions que pose le chercheur à ses collègues à l’autre bout du monde trouvent leurs réponses pendant la nuit, alors qu’il aurait fallu attendre plusieurs semaines auparavant. Ces projets qui ne dorment jamais ne sont pas rares, ils existent déjà : ils s’appellent Linux, Wikipédia, OLPC… Mais ce nouveau cycle temporel a sa contrepartie. C’est le turc mécanique d’Amazon, ces "tâches d’intelligences humaines", cet outsourcing qui n’apporte ni avantage, ni contrat, ni garantie à ceux qui y souscrivent. C’est le côté obscur de la mondialisation intellectuelle rendue possible par l’internet.

Pour Barry C. Smith, directeur de l’Institut de l’école de philosophie de l’université de Londres, internet est ambivalent. "Le privé est désormais public, le local global, l’information est devenue un divertissement, les consommateurs des producteurs, tout le monde est devenu expert"… Mais qu’ont apporté tous ces changements ? L’internet ne s’est pas développé hors le monde réel : il en consomme les ressources et en hérite des vices. On y trouve à la fois le bon, le fade, l’important, le trivial, le fascinant comme le repoussant. Face à l’accélération et l’explosion de l’information, notre désir de connaissance et notre soif à ne rien manquer nous poussent à grappiller "un petit peu de tout et à chercher des contenus prédigérés, concis, formatés provenant de sources fiables. Mes habitudes de lecture ont changé me rendant attentif à la forme de l’information. Il est devenu nécessaire de consommer des milliers de résumés de revues scientifiques, de faire sa propre recherche rapide pour scanner ce qui devrait être lu en détail. On se met à débattre au niveau des résumés. (…) Le vrai travail se faire ailleurs." Il y a un danger à penser que ce qui n’apporte pas de résultat à une requête sur l’internet n’existe pas, conclut le philosophe.

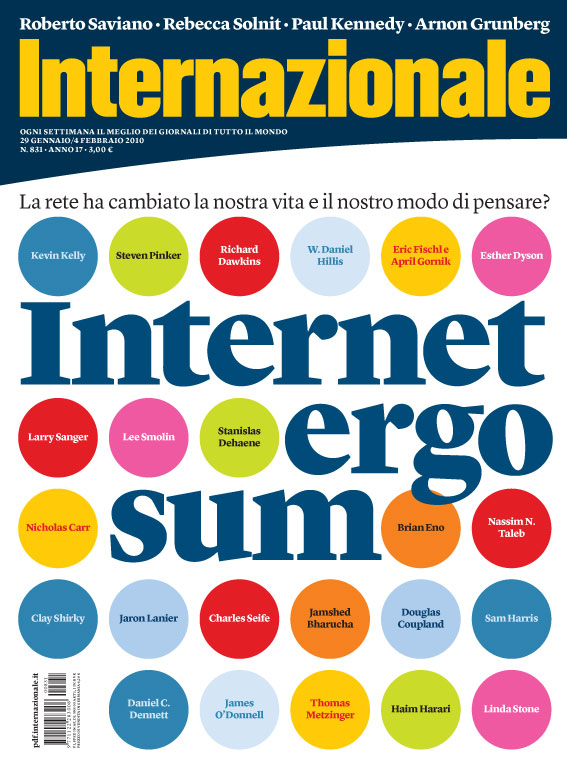

ON THE COVER

INTERNET ERGO SUM

The network has changed our

way of thinking? Meet artists, intellectuals and

Scientists around the world. From Kevin Kelly to Brian Eno, from

Richard Dawkins, to Clay Shirky, to Nicholas Carr

The new Apple iPad isn’t the half of it. The torrent of internet information is forcing us to change the way we think

If there's something that fascinates me about the digital age, it's the evolution of the human psyche as it adjusts to the rapid expansion of informational reach and acceleration of informational flow.

The Edge Foundation, Inc. poses one question a year to be batted around by deep thinkers, this year: How Is The Internet Changing The Way You Think? One contribution that's bound to infuriate those of us of an older persuasion (I'll raise my hand) came from Marissa Mayer, the V.P. for Search Products & User Experience at Google.

The Internet, she posits, has vanquished the once seemingly interminable search for knowledge.

"The Internet has put at the forefront resourcefulness and critical-thinking," writes Mayer, "and relegated memorization of rote facts to mental exercise or enjoyment." She says that we now understand things in an instant, concepts that pre-Web would have taken us months to figure out.

So, basically, you don't have to memorize the The Gettysburg Address anymore, you just have to Google it or link to it. But here's my question: If you can Google it, does that mean you really understand it?

A favorite writer of mine, Nicholas Carr, who deals with all matters digital, cultural and technological has a good answer to that question. In his reply to Marissa Mayer, Carr offers a potent analysis of the difference between knowing and meaning.

He uses (brace yourself) a critical exploration of Robert Frost's poetry by Richard Poirier —Robert Frost: The Work of Knowing— to challenge what I might call the Google mentality.

"It's not what you can find out," he wrote. "Frost and (William) James and Poirier told us, it's what you know."

Gathering facts is not the same as gathering knowledge.

In 1953, when the internet was not even a technological twinkle in the eye, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin famously divided thinkers into two categories: the hedgehog and the fox: "The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.”

Hedgehog writers, argued Berlin, see the world through the prism of a single overriding idea, whereas foxes dart hither and thither, gathering inspiration from the widest variety of experiences and sources. Marx, Nietzsche and Plato were hedgehogs; Aristotle, Shakespeare and Berlin himself were foxes.

Today, feasting on the anarchic, ubiquitous, limitless and uncontrolled information cornucopia that is the web, we are all foxes. We browse and scavenge thoughts and influences, picking up what we want, discarding the rest, collecting, linking, hunting and gathering our information, social life and entertainment. The new Apple iPad is merely the latest step in the fusion of the human mind and the internet. This way of thinking is a direct threat to ideology. Indeed, perhaps the ultimate expression of hedgehog-thinking is totalitarian and fundamentalist, which explains why the regimes in China and Iran are so terrified of the internet. The hedgehogs rightly fear the foxes.

Edge (www.edge.org), a website dedicated to ideas and technology, recently asked scores of philosophers, scientists and scholars a simple but fundamental question: "How is the internet changing the way you think?” The responses were astonishingly varied, yet most agreed that the web had profoundly affected the way we gather our thoughts, if not the way we deploy that information.

If there's something that fascinates me about the digital age, it's the evolution of the human psyche as it adjusts to the rapid expansion of informational reach and acceleration of informational flow.

The Edge Foundation, Inc. poses one question a year to be batted around by deep thinkers, this year: How Is The Internet Changing The Way You Think? One contribution that's bound to infuriate those of us of an older persuasion (I'll raise my hand) came from Marissa Mayer, the V.P. for Search Products & User Experience at Google.

The Internet, she posits, has vanquished the once seemingly interminable search for knowledge.

"The Internet has put at the forefront resourcefulness and critical-thinking," writes Mayer, "and relegated memorization of rote facts to mental exercise or enjoyment." She says that we now understand things in an instant, concepts that pre-Web would have taken us months to figure out.

So, basically, you don't have to memorize the The Gettysburg Address anymore, you just have to Google it or link to it. But here's my question: If you can Google it, does that mean you really understand it?

A favorite writer of mine, Nicholas Carr, who deals with all matters digital, cultural and technological has a good answer to that question. In his reply to Marissa Mayer, Carr offers a potent analysis of the difference between knowing and meaning.

He uses (brace yourself) a critical exploration of Robert Frost's poetry by Richard Poirier —Robert Frost: The Work of Knowing— to challenge what I might call the Google mentality.

"It's not what you can find out," he wrote. "Frost and (William) James and Poirier told us, it's what you know."

Gathering facts is not the same as gathering knowledge.

His name is John Brockman and he is a special type: he queries the best scientists, asks them to pose their most pressing questions, brings them together on his site edge.org to converse about everything and sometimes they also meet in the flesh, in California or in Paris. He often encourages them to write about their visionary ideas, which become best-selling books.

Brockman is much more than a publishing and cultural impresario. He is unique, someone who is not replicable in the universe of science where replicability and falsifiability are notoriously non-negotiable rules.

Brockman is much more than a publishing and cultural impresario. He is unique, someone who is not replicable in the universe of science where replicability and falsifiability are notoriously non-negotiable rules.

That is why his posing questions, like a petulant boy genius, to the world's greatest thinkers is disorienting. Guest of the Festival of Science in Rome, he has distributed his provocations there too, ranging from the subject of Alan Turing, the unfortunate and mythical English scientist who founded the digital world which led to his new Question of 2010, which has inspired a group of American thinkers: "How does the Internet change the way you think?" He explains: "I stress the "you" instead of "we". After oscillating between the two, I chose the "you" because Edge is a conversation. The "we" would have suggested a public voice instead, of experts on stage."

"The question," he adds, "is based on the idea of my friend and former collaborator James Lee Byars.

What did Byars do?

|

Photo of John Brockman |

"In 1971, he went to Harvard Square and there founded the "World Question Center". He was convinced that to reach the edge of knowledge, it was not in fact necessary to read 6 million volumes in the university library: he believed it was enough to collect the most sophisticated minds in one place and lock the door until they asked each other the questions they were asking themselves. This idea is in perfect harmony with the logic of today's digital environment, in which everything can be assembled with the power of algorithms: it is the reality of the Petabyte Revolution.

Explain what this is.

"The accumulation of data is such that instead of starting an argument and then testing it with a series of experiments, the data already stored may be investigated in order to discover what is hidden."

Does this mean that the scientific method, which is sacrosanct, is about to change?

"In any case, yes, there is someone who has already made this hypothesis. I think of Craig Venter, who is deciphering the Genome: he is the greatest advocate in the private sector of a continuing growth in computational power. He collects billions of pieces of genetic information from various sources, including the oceans and processes them using computers: it is a scale of data never dealt with before."

And the responses to the "Question"? What is currently the one that has intrigued the most?

"George Dyson's response: "kayak vs. canoe." It refers to two opposite approaches to achieving the same result, the construction of boats. The first entails the assembly of a skeleton from bits and pieces, and the latter involves carving out of whole trees. The Internet has produced a similar gap: we were manufacturers of kayaks, used to seeking any information that could keep us afloat, and now, instead, we must learn to shape the canoe, removing everything that is not necessary and bringing to light the hidden heart of knowledge. Whoever doesn't acquire the new skills will be forced to row his crudely carved tree trunks."

He never tires of prodding scientists: his latest book, This Will Change Everything, is dedicated to ideas that will shape the future. Are you sure to have discovered the best?

"In another career I acted as an impresario. I was the guy who ran the theatre, standing in the back, turning the lights on and off. This is my role and in this case, the basic concept I present is that new media creates new perceptions: science creates the technology to use and we recreate ourselves in its image. Until recently no one had ever thought of this process. It was unconscious. No one has voted on the printing press, electricity, radio, tv, cars, airplanes. Nobody voted for penicillin, nuclear energy, space travel. No one voted for computers, Internet, email, Google, cloning. Now we move towards a new definition of life and a condition in which science is not only news, but The News. Politicians can play catch up and and chase the developments. James Watson, the man who was co-discoverer of the double helix of DNA and who is currently only only one of two people to have posted his genetic code on the Internet, is said to oppose any interference. The other person, Craig Venter, is preparing to create artificial life: And even now, he can move a drop of genetic material from one dish to another and...your dog can become a cat. The result is that everything will change and therefore, the question for the new book was: What game-changing scientific revolution do you expect to live to see?

You had 151 responses: reveal your favorite.

"Kevin Kelley impressed me: he spoke of a new type of mind, amplified by the Internet, evolving, and able to start a new phase of evolution outside of the body. And so many others... Ed Regis and "molecular manufacturing", about the production of new molecules as one of the frontiers of nanotechnology. William Calvin and our vulnerability to climate and our intellectual capacity to react. Nicholas Humphrey and rebellious impulses of human nature: as we transform ourselves, we nevertheless remain the same, distracted by violence and politics. Freeman Dyson and telepathy, with the possibility of direct communication from one brain to another. And finally, a novelist, Ian McEwan. He confessed to wanting to live long enough to witness the final triumph of solar technology.