THE PANCAKE PEOPLE, OR, "THE GODS ARE POUNDING MY HEAD"

A Statement

When I began rehearsing, I thought The Gods Are Pounding My Head would be totally metaphysical in it's orientation. But as rehearsals continued, I found echoes of the real world of 2004 creeping into many of my directorial choices. So be it.

Nevertheless, this very—to my mind—elegiac play does delineate my own philosophical dilemma. I come from a tradition of Western culture in which the ideal (my ideal) was the complex, dense and "cathedral-like" structure of the highly educated and articulate personality—a man or woman who carried inside themselves a personally constructed and unique version of the entire heritage of the West.

And such multi-faceted evolved personalities did not hesitate— especially during the final period of "Romanticism-Modernism"—to cut down , like lumberjacks, large forests of previous achievement in order to heroically stake new claim to the ancient inherited land— this was the ploy of the avant-garde.

But today, I see within us all (myself included) the replacement of complex inner density with a new kind of self-evolving under the pressure of information overload and the technology of the "instantly available". A new self that needs to contain less and less of an inner repertory of dense cultural inheritance—as we all become "pancake people"—spread wide and thin as we connect with that vast network of information accessed by the mere touch of a button.

Will this produce a new kind of enlightenment or "super-consciousness"? Sometimes I am seduced by those proclaiming so—and sometimes I shrink back in horror at a world that seems to have lost the thick and multi-textured density of deeply evolved personality.

But, at the end, hope still springs eternal...

___

A Question

Can computers achieve everything the human mind can achieve?

Human beings make mistakes. In the arts—and in the sciences, I believe?—those mistakes can often open doors to new worlds, new discoveries and developments—the mistake itself becoming the basis of a whole new world of insights and procedures.

Can computers be programmed to 'make mistakes' and turn those mistakes into new and heretofore unimaginable developments?

As Richard Foreman so beautifully describes it, we've been pounded into instantly-available pancakes, becoming the unpredictable but statistically critical synapses in the whole Gödel-to-Google net. Does the resulting mind (as Richardson would have it) belong to us? Or does it belong to something else?

THE GÖDEL-TO-GOOGLE NET

George Dyson

GEORGE DYSON, science historian, is the author of Darwin Among the Machines.

___

THE GÖDEL-TO-GOOGLE NET

Richard Foreman is right. Pancakes indeed!

He asks the Big Question, so I've enlisted some help: the Old Testament prophets Lewis Fry Richardson and Alan Turing; the New Testament prophets Larry Page and Sergey Brin.

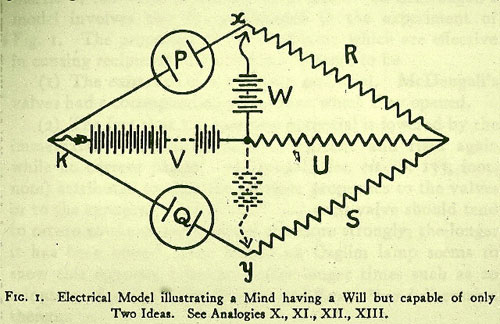

Lewis Fry Richardson's answer to the question of creative thinking by machines is a circuit diagram, drawn in the late 1920s and published in 1930, illustrating a self-excited, non-deterministic circuit with two semi-stable states, captioned "Electrical Model illustrating a Mind having a Will but capable of only Two Ideas."

Machines that behave unpredictably tend to be viewed as malfunctioning, unless we are playing games of chance. Alan Turing, namesake of the infallible, deterministic, Universal machine, recognized (in agreement with Richard Foreman) that true intelligence depends on being able to make mistakes. "If a machine is expected to be infallible, it cannot also be intelligent," he argued in 1947, drawing this conclusion as a direct consequence of Kurt Gödel's 1931 results.

"The argument from Gödel's [theorem] rests essentially on the condition that the machine must not make mistakes," he explained in 1948. "But this is not a requirement for intelligence." In 1949, while developing the Manchester Mark I for Ferranti Ltd., Turing included a random number generator based on a source of electronic noise, so that the machine could not only compute answers, but occasionally take a wild guess.

"Intellectual activity consists mainly of various kinds of search," Turing observed. "Instead of trying to produce a programme to simulate the adult mind, why not rather try to produce one which simulates the child's? Bit by bit one would be able to allow the machine to make more and more ‘choices' or ‘decisions.' One would eventually find it possible to program it so as to make its behaviour the result of a comparatively small number of general principles. When these became sufficiently general, interference would no longer be necessary, and the machine would have ‘grown up'"

That's the Old Testament. Google is the New.

Google (and its brethren metazoans) are bringing to fruition two developments that computers have been waiting for sixty years. When John von Neumann's gang of misfits at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton fired up the first 32 x 32 x 40 bit matrix of random access memory, no one could have imagined that the original scheme for addressing these 40,960 ephemeral bits of information, conceived in the annex to Kurt Gödel's office, would now have expanded, essentially unchanged, to address all the information contained in all the computers in the world. The Internet is nothing more (and nothing less) than a set of protocols for extending the von Neumann address matrix across multiple host machines. Some 15 billion transistors are now produced every second, and more and more of them are being incorporated into devices with an IP address.

As all computer users know, this system for Gödel-numbering the digital universe is rigid in its bureaucracy, and every bit of information has to be stored (and found) in precisely the right place. It is a miracle (thanks to solid-state electronics, and error-correcting coding) that it works. Biological information processing, in contrast, is based on template-based addressing, and is consequently far more robust. The instructions say "do X with the next copy of Y that comes around" without specifying which copy, or where. Google's success is a sign that template-based addressing is taking hold in the digital universe, and that processes transcending the von Neumann substrate are starting to grow. The correspondence between Google and biology is not an analogy, it's a fact of life. Nucleic acid sequences are already being linked, via Google, to protein structures, and direct translation will soon be underway.

So much for the address limitation. The other limitation of which von Neumann was acutely aware was the language limitation, that a formal language based on precise logic can only go so far amidst real-world noise. "The message-system used in the nervous system... is of an essentially statistical character," he explained in 1956, just before he died. "In other words, what matters are not the precise positions of definite markers, digits, but the statistical characteristics of their occurrence... Whatever language the central nervous system is using, it is characterized by less logical and arithmetical depth than what we are normally used to [and] must structurally be essentially different from those languages to which our common experience refers." Although Google runs on a nutrient medium of von Neumann processors, with multiple layers of formal logic as a base, the higher-level meaning is essentially statistical in character. What connects where, and how frequently, is more important than the underlying code that the connections convey.

As Richard Foreman so beautifully describes it, we've been pounded into instantly-available pancakes, becoming the unpredictable but statistically critical synapses in the whole Gödel-to-Google net. Does the resulting mind (as Richardson would have it) belong to us? Or does it belong to something else?

Turing proved that digital computers are able to answer most—but not all—problems that can be asked in unambiguous terms. They may, however, take a very long time to produce an answer (in which case you build faster computers) or it may take a very long time to ask the question (in which case you hire more programmers). This has worked surprisingly well for sixty years.

Most of real life, however, inhabits the third sector of the computational universe: where finding an answer is easier than defining the question. Answers are, in principle, computable, but, in practice, we are unable to ask the questions in unambiguous language that a computer can understand. It's easier to draw something that looks like a cat than to describe what, exactly, makes something look like a cat. A child scribbles indiscriminately, and eventually something appears that happens to resemble a cat. A solution finds the problem, not the other way around. The world starts making sense, and the meaningless scribbles are left behind.

"An argument in favor of building a machine with initial randomness is that, if it is large enough, it will contain every network that will ever be required," advised Turing's assistant, cryptanalyst Irving J. Good, in 1958. Random networks (of genes, of computers, of people) contain solutions, waiting to be discovered, to problems that need not be explicitly defined. Google has answers to questions no human being may ever be able to ask.

Operating systems make it easier for human beings to operate computers. They also make it easier for computers to operate human beings. (Resulting in Richard Foreman's "pancake effect.") These views are complementary, just as the replication of genes helps reproduce organisms, while the reproduction of organisms helps replicate genes. Same with search engines. Google allows people with questions to find answers. More importantly, it allows answers to find questions. From the point of view of the network, that's what counts. For obvious reasons, Google avoids the word "operating system." But if you are ever wondering what an operating system for the global computer might look like (or a true AI) a primitive but fully metazoan system like Google is the place to start.

Richard Foreman asked two questions. The answer to his first question is no. The answer to his second question is yes.