HOW PEOPLE SEE THEMSELVES

In today's media society, in which hundreds of different media compete for the attention of viewers, readers and listeners, a great deal of importance is attached to presenting oneself. Those who know how to present themselves get noticed, and a whole raft of consultants from different horizons make sure that their protégés are presented as effectively as possible. The opportunities of personal representation and self-presentation have become democratised to an extent that would have been unimaginable many years ago. Nowadays anyone who wants to draw attention to themselves and communicate to the public an image of themselves can to all intents and purposes do so.

As a publisher in a media company with a global presence, who is confronted on a daily basis with a plethora of images of people portraying themselves to the media, but who has remained in close touch with his field of study — art history – I naturally am always interested in the history of such phenomena. I should therefore like to take a look back at the early stages of modern portrait art and follow its development from then until now from the following perspective: what does the self-presentation of the people being portrayed say about the image that they have of themselves and that they want to convey to a specific community?

I take a consciously undogmatic approach to this and pick out just a few significant examples, which I believe are characteristic of the forms of self-presentation we see nowadays. Most of the portraits I present in this paper we know were commissioned. Although there are only a few cases – such as the portrait of Napoleon on horseback by Jacques Louis David – where we know that the person who commissioned the work approved greatly of this mode of pictorial representation, as regards commissioned portraits we can basically assume that those were largely identical to the image that the persons being portrayed had of themselves and wanted to convey through the portrait.

My analysis of portraits deliberately does not focus on the great self-portraits of artists, which the genre spawned over the course of the century, from the enigmatic self-portraits of Rembrandt in costume to the inimitable personal accounts of Cézanne and Max Beckmann.

What these portraits of artists show bears no relation to what interests me about self portrayals. Because, unlike portraits of members of the middle class, these portraits do not reveal anything about the new self-assurance of a class whose standing had risen, but are rather the expression of an existential wonder of the cosmos, their own lives and the period and environment in which the artists lived.

The images I have drawn on for my reflections can be described, to use an expression coined by my professor, Hans Sedlmayr, as "critical forms" of their time. The critical forms approach makes it possible, when analysing works of art, "to draw on extremely diverse phenomena from a source which is the unifying centre of otherwise unrelated, unchallengable factors from art and cultural history." We can thus fall back on "low forms" of artistic expression. [1] The latter in particular enables us relatively easily to create a link with current forms of individual representation.

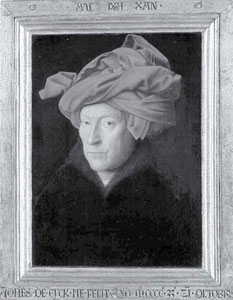

I would like to start with a painting from the early days of modern portrait art, which, in my opinion, is characteristic of all the new possibilities of expression in this mode of painting: Jan van Eyck's "Man in a Turban", 1432.

Fig. 1

Demonstration of the new middle-class self-assurance: Man in A Turban by Jan van Eyck, 1432, National Gallery, London

This painting is generally regarded by more recent research as a self-portrait of the artist. According to Hans Belting, the gaze of the man in the portrait is so self-assured and inquiring that one can scarcely take one's eyes off him, [2] and the headwear, a bulky red turban with "a strangely bound turban", denotes "the vanity of the artist in relation to his self-portrayal ".The portrait of Jan van Eyck whom Hans Belting holds responsible for the invention of painting, bears powerful testimony to the new self-assurance of a class whose standing had risen and their pretension to express this in their portraits.

The period between 1400 and 1450, during which the portrait was painted, was marked by two very different artistic currents: In Italy, Alberti's treatise on painting laid the foundations for his future theory on perspective; at the same time, in the trading towns of Gent and Bruges, which had close commercial ties with Italy, with the result that new artistic ideas were quickly exported, a completely new reality in terms of pictorial representation was emerging. Hans Belting sees in the fusion of the two — the schematic, inner-visual aesthetics of Italian art and the pragmatism of the new middle-class culture in the North — the basis for the invention of painting as a genre. For him, portrait art is a symbol of a painted anthropology, in which the inner and outer visions of the world are fused. [3]

The modern portrait, which Jan van Eyck's self-portrait embodies, was born out of the reciprocal tension between the established nobility and those rising to the middle-classes.

Whoever managed to climb the social ladder automatically won the right, so to speak, to have their own portrait painted, which in earlier times had been the preserve of the saints. Using a few examples, I would now like to show how those classes which were climbing the social ladder at that time used the portrait to give visibility to their claim to power and status, how the painted portrait lost this function following the invention of photography and how the portrait, as a result of the opening up of the media to anyone wanting to get themselves seen, has been superseded by other forms of expression.

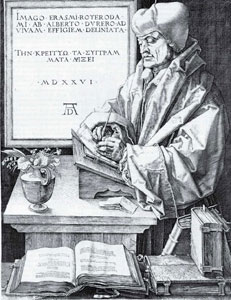

Dürer's famous engraving of Erasmus of Rotterdam reflects perfectly the rationale behind portraits of the middle classes at that time, namely that they were intended to be the staged imago of an individual: On the one hand, the engraving is a portrait and, as such, resembles Erasmus, but at the same time it also reflects, in the way that it presents this great humanist, his personal, cultural and historical importance.

Fig. 2

Presenting a middle-class humanist: Erasmus of Rotterdam, copperplate engraving by Albrecht Dürer, 1526

Dürer also portrays studiolo decoration, like those seen in many of Hieronymus's works, and in doing so identifies the person being portrayed as a scholar. The use of the copperplate engraving technique, which emerged in the Upper Rhine region at around the same time as the oil paintings of the van Eyck brothers, and was, along with the woodcut technique, the first pictorial medium that found an easy way of making copies, indicates that the portrait was designed to convey a certain image of the humanist to interested members of the public. The inscription on the board next to Erasmus provides an additional explanation as to how the picture should be interpreted: the artist is disassociating the imago and the effigy of Erasmus and points out to the beholder in Latin and Greek that the real image of Erasmus can only be understood through the works that are pictured in the foreground.

An excellent example of the great claim that middle-class merchants, who had now moved up the social ladder, laid to having their portraits painted is Hans Holbein's portrait of the merchant Georg Gisze, dated 1532.

Fig. 3

A display of credibility and market knowledge: Portrait of the merchant Georg Gisze by Hans Holbein, 1532, Gemäldegalerie Berlin

There is no detail in this portrait of a proud young man that cannot be attributed to this claim for his standing in society to be represented, from the Oriental rug, the Vase filled with cloves and rosemary, the graceful balance and the golden table clock to the hand stamp bearing the tradesman's mark. Gisze became, as a result of this portrait, a Mercator doctus, a merchant on the cutting-edge of society at that time. He was born in Danzig, but wanted to be presented as a successful merchant on the London trading exchange in order to convey a certain image of himself to the inner circle of merchants in the City. The contracts and many other objects surrounding the merchant are meant, above all, to mark him out as an extremely credible person in money matters and a good connoisseur of world markets. This was of great importance during the period of rule of Henry VIII, since it was at this time that the first wave of globalisation was taking place.

Portrait presentations of the recently elevated middle classes led to the creation of yet another genre in the form of the Dutch group portraits. An excellent example of this is Rembrandt's portrait of "The Syndics of the Clothmaker's Guild", dated 1662, which hung in the main room of the guild in Amsterdam along with five other group portraits of its members.

Fig. 4

Strength lies in a group of like-minded people: The Syndics of the Clothmaker's Guild by Rembrandt, 1662, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

At this juncture I shall disregard the research into the significance of this painting and focus on the group portrait in terms of it being a critical phenomenon of Dutch portrait painting. Through this genre something came to pass in middle-class Holland that was an anomaly in the absolutist Europe of that time: The individual was portrayed as a member of a like-minded group and constituted within this group its "imaginary, ideal image, namely that of a harmonious, conflict-free relationship between individuals and the community ". [4] The recently successful elites felt at their strongest within a group and, through this type of group portrait, they set middle-class self-assurance in opposition to the absolutist court society.

At around the same time that Rembrandt painted the The Syndics of the Clothmaker's Guild in Amsterdam, the 23-year-old King of France, Louis XIV, was informing his ministers that he would be taking control of state affairs, thus becoming Head of State, before going on to dismiss most of them. In keeping with his motto, "In my heart I prefer fame above all else", he later had a portrait of himself posing as the absolutist ruler painted by Hyacinthe Rigaud.

Fig. 5

Depiction of a claim to absolute power: Louis XIV. by Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1701, Louvre, Paris

The portrait shows the 63-year-old ruler in a pose that expresses perfectly his claim to absolute power: He is draped in his heavy royal blue coronation robes ornamented with the French fleur-de-lys, has one foot placed slightly to the fore, his right hand on his sceptre, his left resting on his sword. A truly regal posture and an appearance that one could hardly imagine more magnificent. The highly theatrical nature of the depiction conveyed by the painting is reinforced by the powerful drapery that the king is posing in front of, as well as the light that is being projected from the foreground as if from a spotlight.

Similarly theatrical in nature, but also drawing on the tradition of painting portraits of emperors on horseback, is Jacques Louis David's portrait, 100 years later, of the then 31-yearold Napoleon Bonaparte, who at that time had headed a coup that put an end to revolutionary rule and had established himself as First Consul and Head of State.

Fig. 6

Pretensions to rule: the emperor posing on horseback: Napoleon crossing the St. Bernard Pass, by Jacques Louis David, 1800, Museum in Malmaison

The portrait shows Napoleon in a flowing cape on a rearing white horse. His right hand is pointing towards the St. Bernard Pass, which must be safely crossed with an army of 30 000 men. On the rocks in the bottom left-hand corner his name, as well as those of his great role models, Hannibal and Carolus Magnus, are hewn in the stone. Legend has it that Napoleon did not cross the Alps on the back of a noble horse, which would barely have been able to stand up to the ice-cold conditions of the journey, but rather on the back of a mule. However, this portrait is not meant to be an exact depiction of his crossing the pass with a huge army, which was a heroic act that secured victory for the French army over the Austrians. The portrait of the Emperor on horseback was supposed to depict the First Consul's claim to political power. In Napoleon's eyes, David had found such a convincing way of doing this that he commissioned him to paint three replicas of the portrait.

The portrait as an expression of seeing oneself as a ruler reached a pinnacle with David's magnificent portrait of Napoleon, but this was a solitary success since, by this time, the heyday of portrait painting had already been and gone. A period of technological progress had opened, which was to leave its mark very firmly on portrait art. In 1826 in Chalon-sur-Saone Nicéphore Niépce took the first ever photograph with an exposure time of 8 hours. This invention was to spell disaster for French portrait painters.

It has been estimated that at that time around 20 000 painters in Paris alone depended on this for their living. Over the next 15 years, over half of them would find themselves out of work. People who wanted to have their portraits taken felt that a photograph could give them a more faithful visual representation of the image of themselves that they wanted to see than a painting could. Henceforth, fewer and fewer people wanted to have their portraits painted, especially as photography techniques were developing so quickly that by 1841 the first major photography exhibition had been held in Paris.

Over the next few decades, many figurative paintings by artists such as Delacroix, Manet and Cézanne bear eloquent testimony to the artist's quest for new outlets for his work. The Munich-based artist, Franz von Lenbach, found an original and clever approach, as shown in his portraits of Chancellor Bismarck, which achieved a successful symbiosis between photography and painting. Lenbach, who brought a touch of genius to Bismarck's portraits, hit upon the public taste of that period. His portraits, which were marketed, so to speak, in the form of postcards and albums, alluded to the political greatness of a great man from a great era.

However, as of 1900, artistic tastes ("Kunstwollen"), as defined by Riegel, headed in a completely different direction. With the emergence of a new generation of artists and paintings by Klimt, Schiele, Kokoschka, the French Fauve painters and the "Brücke" artists from Dresden with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner at the fore, portrait painting experienced a renaissance and developed a quality that set it apart from photography, which at that time still only afforded very limited possibilities. The most innovative artist within this genre was Picasso, who experimented with every option possible in portrait painting, and came up with such diverse creations as his 1906 portrait of Gertrude Stein and his 1941 portrait of Dora Maar.

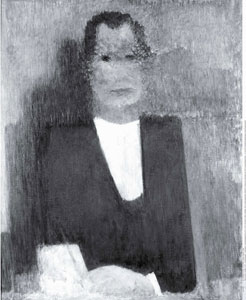

The extent of the difficulties that the demise of realism spelt in general for panel painting as a medium of representation can be seen by taking a look at Georg Meistermann's portrait of former Chancellor, Willy Brandt. The painting constitutes a critical form of the representative portrait insomuch as it is representative of the artistic tastes of a particular period, but it provides virtually no recognisable feature of the person being portrayed and fails to reflect his standing. At any rate, and this was the noise coming out of Willy Brandt's inner circle at that time – he in fact never officially commented on the portrait — , his blood-red, virtually abstract portrait meant little to him. His successor, Helmut Schmidt, had the portrait removed from the gallery in the Chancellery, and Helmut Kohl replaced it with a realistic portrait of Brandt.

Fig. 7

Barely any recognisable features of the person being portrayed: Portrait of Willy Brandt by Georg Meistermann, 1978, Landesvertretung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Berlin

At the same time that Meistermann was putting the finishing touches to his unpopular portrait of the Chancellor, Andy Warhol was reinventing the portrait genre by developing a technique that combined the technique of the photographic image with silkscreen printing and acrylic overpainting techniques. His works, which bestowed an icon-like aura upon the people he portrayed, became the authoritative portrait mode of a new international community of celebrities.

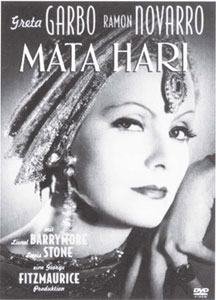

Warhol was particularly interested in how reality was reflected in the visual world of the mass media. Warhol had a special interest in the legends of Hollywood stars of past and present, such as Greta Garbo, Elizabeth Taylor und Marilyn Monroe, which the young, smalltown boy had grown up with. The visual repertoire of the celebrity cult first emerged in the 1930s with the emergence of the new stars of talking movies, such as Greta Garbo, Marlene Dittrich or Jean Harlow. Warhol was fascinated by the uniformity of the make-up and presentation of star portraits, and how, apart from minor changes, this has remained the case right up until the present day. Warhol got the pictures he used to create his silkscreen prints from film posters, illustrated photos and the photo pages of tabloid newspapers, which reported on the most recent events in the lives of the film stars of that era.

Fig. 8

Iconic portrayal of an actress in the 1930s: Greta Garbo on the poster for the film "Mata Hari", 1931

Fig. 9

The staged portrait of a star as an ageless creation: a film still of Greta Garbo playing Mata Hari

Fig. 10

Revival of the star portrait using modern technology: Greta Garbo as Mata Hari by Andy Warhol, 1981, silkscreen print with acrylic overpainting

The iconic portraits, in the style of star portraits, which Warhol made of internationally renowned celebrities, were extremely popular. Warhol had evidently tapped into the pulse of the age. The way in which he portrayed people using technology also had a great influence on advertising.

The urge for visual representation has remained right through to the present day. However, visual arts and painting no longer play an important role. For members of the media society the only question of importance is: "How often do I appear in the media, in which ones, and how often am I quoted?" The whys and wherefores of this can vary greatly. An actor's photo is placed on the front cover of a TV magazine in order to increase the audience ratings of a given programme. A politician, who is in the public eye thanks to his appearances on a host of talk shows, is interested in enhancing his own popularity ratings. An author, whose latest novel is discussed on a book programme, hopes that this will lead to more copies of his novel being sold.

Andy Warhol had a profound conviction that "Images need to be shared". The better known your face is in the new economy of attention seeking, the higher your market value and your personal rate of return. "How many entries in Google do you have?" is a question that today's twentysomethings ask each other in order to check how important they are.

The aim of other questions, such as "How many people read my weblog and respond to it?" or "How many photos are there of me on the Flickr platform?" is to ascertain how one's role and standing are being portrayed and relayed. In fact, the search engine A9 contains a tool that enables you to find all the written content and images that have been published about you by online newspapers and magazines.

The boundaries between the public and private spheres are becoming increasingly blurred. New media are thereby able to take over old functions, such as the large advertising billboards with portraits of famous personalities splashed across them that can be seen in all major cities across the globe. One can, with a bit of imagination, see in this trend a continuation of the mural paintings of the Renaissance, with the notable difference that today's images generate advertising revenue. The portrait photo of prominent figures has become an advertising medium that draws our attention towards a brand or a product and makes them more valuable and desirable.

During the 2006 Football World Cup, the sportswear firm Adidas, which makes the German football squad's strip and is one of the main sponsors of the World Cup, showed portrait images of the football stars on its payroll, such as Michael Ballack, Oliver Kahn und David Beckham, on TV, in print and online media and on huge outdoor billboards. The estimated cost of 500 million euros to run this campaign shows how much influence prominent figures are deemed to have on the image and turnover of a brand nowadays.

Fig. 11

Image campaign using portraits of prominent figures: Outdoor advertisement for Adidas featuring Oliver Kahn, 2006, Munich Airport

[photo credit: German News Agency "ddp"]

More than two thousand years after a ruler, Augustus, used for the very first time the minting technique to bring his face to the people, the possibilities for getting one's picture shown in public have increased many-fold. Print media, TV and the Internet have teamed up and have made the motto of the hippie generation of late 60s San Francisco — "Expose yourself!" — a reality.

Nowadays anyone who wants to draw attention to themselves can. The Internet enables us to become multi-media media producers. Since it started up a year ago, over 50 million people have already uploaded personal short videos onto the video platform YouTube.com. The portrait which enabled the new middle-classes of the 15th century, following their rise in status, to fulfill their desire for representation, has experienced many changes over the centuries. These have related on the one hand, to developments in society and, on the other, to technological innovations. However, the claim to representation made by the aspiring classes has remained and can serve as a marker for the development of portrait forms over the course of the 21st century.