Events: On the Road

This year's Edge-Serpentine Gallery collaboration took place in London at part of the Serpentine's "Extinction Marathon: Visions of the Future" event, at the Serpentine Sackler Gallery's extension, designed by Zaha Hadid, on Oct. 18, 2014. The 2-hour event, which was live-streamed, is presented, here in its entiretly, on Edge.

The first hour was a converseation between Stewart Brand and Richard Prum on whether of not the prospect of "de-extinction" changes how we think about extinction. For the second hour, Molly Crockett introduced four Edgies—Helena Cronin, Jennifer Jacquet, Steve Jones, and Chiara Marletto, who gave 10-minute talks with their perspectives on the subject of extinction. This was followed by a panel.

NEW—COMPLETE VIDEO AND TEXT

Part I: "DE-EXTINCTION": STEWART BRAND & RICHARD PRUM

With Hans Ulrich Obrist and John Brockman

Does the prospect of "de-extinction" change how we think about extinction? Conservation science is shifting from being species-centric to function-centric, focussing on the overall health of ecosystems. Does the extinction of a species leave a "gap in nature" that can only be filled by returning the species to life and to the wild? Or will a functionally close relative serve? Is a de-extincted species really nothing more than a functionally close relative anyway? If it is too difficult and expensive to revive every extinct species, what are the criteria for deciding which ones to work on? Humans are the ones deciding. What ethics and aesthetics should guide those decisions?

STEWART BRAND is the Founder of the "The Whole Earth Catalog" and Co-founder of The Long Now Foundation and Revive and Restore; Author, Whole Earth Discipline.

Stewart Brand's Edge Bio Page

RICHARD PRUM is an Evolutionary Ornithologist at Yale University, where he is the Curator of Ornithology and Head Curator of Vertebrate Zoology in the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History. He is working on a book about duck sex, aesthetic evolution, and the origin of beauty.

Richard Prum's Edge Bio Page

[Continue to Part I—Video & Text]

Part II: "EDGIES ON EXTINCTION"

Molly Crockett introduces and moderates an event of four 10-minute talks by Helena Cronin, Jennifer Jacquet, Steve Jones, and Chiara Marletto, followed by a discussion joined by Hans Ulrich Obrist, and John Brockman.

HANS ULRICH OBRIST: When we spoke with John Brockman about the Extinction Marathon he suggested, as a second part—as I mentioned in previous marathons we got the Edge community to realize maps and different formulas, and John thought today it would be wonderful to do a panel with UK based scientists who are part of the Edge community. We are extremely delighted that we now will have four presentations by Helena Cronin, by Chiara Marletto, by Jennifer Jacquet, and by Steve Jones. We welcome Steve Jones back to the Serpentine because he was part of the 2007 Experiment Marathon with Olafur Eliasson. The entire panel will be introduced by Molly Crockett. Molly is an associate professor for experimental psychology and fellow of Jesus college at the University of Oxford. She holds a Ph.D. in experimental psychology from Cambridge and a B.S. in neuroscience from UCLA. Dr. Crockett studies the neuroscience and psychology of altruism, of morality, and self-control. Her work has been published in many top academic journals including Science, PNAS, and also Neuron. Molly Crockett will now introduce Helena, Chiara, Jennifer, and Steve. We then, together with Molly and all the speakers and John, give a panel after that.

MOLLY CROCKETT: I'm very, very pleased to introduce Helena Cronin. She's the co-director of the Center for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science and the director of Darwin at LSE at the London School of Economics. She has many notable publications including the edited series, Darwinism Today, and the award winning, The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection from Darwin to Today, that has been featured in the New York Times' Best Books and Nature's Best Science Books of the Year. Her current research interests focus on the evolutionary understanding of sex differences. Let's give a very warm welcome to Helena and welcome her to the stage. ...

... A strange thing happened on the way to a better world in pursuit of an admirable quest, that is, a world free of sex discrimination where you’re judged on your own qualities and not your sex. Truth and falsity went topsy-turvy. The truth—the silence of sex differences—became dangerous, unmentionable, and in its place the conventional wisdom, which is a ragbag of ideas that have long been extinct but are kept ghoulishly alive by popularity, became the entrenched orthodoxy influencing public thinking, agendas and policy-making, and completely crowding out science and sense.

... A strange thing happened on the way to a better world in pursuit of an admirable quest, that is, a world free of sex discrimination where you’re judged on your own qualities and not your sex. Truth and falsity went topsy-turvy. The truth—the silence of sex differences—became dangerous, unmentionable, and in its place the conventional wisdom, which is a ragbag of ideas that have long been extinct but are kept ghoulishly alive by popularity, became the entrenched orthodoxy influencing public thinking, agendas and policy-making, and completely crowding out science and sense.

My aim is to show you why the current orthodoxy should be abandoned and why, if you really care about a fairer world, the science does matter. It matters profoundly. I’m going to take two examples, both about the professions, because they very well epitomize the orthodox litany: how society systematically discriminates against women, and how at work they are victims of pervasive sexism. ...

HELENA CRONIN is the Co-Director of LSE's Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science; Author, The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection from Darwin to Today. Helena Cronin's Edge Bio Page

There is a new fundamental theory of physics that's called constructor theory, and was proposed by David Deutsch who pioneered the theory of the universe of quantum computer. David and I are working this theory together. The fundamental idea in this theory is that we forumlate all laws of physics in terms of what tasks are possible, what are impossible, and why. In this theory we have an exact physical characterization of an object that has those properties, and we call that knowledge. Note that knowledge here means knowledge without knowing the subject, as in the thoery of knowledge of the philosopher, Karl Popper.

There is a new fundamental theory of physics that's called constructor theory, and was proposed by David Deutsch who pioneered the theory of the universe of quantum computer. David and I are working this theory together. The fundamental idea in this theory is that we forumlate all laws of physics in terms of what tasks are possible, what are impossible, and why. In this theory we have an exact physical characterization of an object that has those properties, and we call that knowledge. Note that knowledge here means knowledge without knowing the subject, as in the thoery of knowledge of the philosopher, Karl Popper.

We’ve just come to the conclusion that the fact that extinction is possible means that knowledge can be instantiated in our physical world. In fact, extinction is the very process by which that knowledge is disabled in its ability to remain instantiated in physical systems because there are problems that it cannot solve. With any luck that bit of knowledge can be replaced with a better one. ...

CHIARA MARLETTO is a Junior Research Fellow at Wolfson College and Postdoctoral Research Assistant at the Materials Department, University of Oxford. Chiara Marletto's Edge Bio Page

I dream about the sea cow or imagine what they would be like to see in the wild, but the case of the Pinta Island giant tortoise was a particularly strange feeling for me personally because I had spent many afternoons in the Galapagos Islands when I was a volunteer with the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society in Lonesome George’s den with him. If any of you visited the Galapagos, you know that you can even feed the giant tortoises that are in the Charles Darwin Research Station. This is Lonesome George here.

I dream about the sea cow or imagine what they would be like to see in the wild, but the case of the Pinta Island giant tortoise was a particularly strange feeling for me personally because I had spent many afternoons in the Galapagos Islands when I was a volunteer with the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society in Lonesome George’s den with him. If any of you visited the Galapagos, you know that you can even feed the giant tortoises that are in the Charles Darwin Research Station. This is Lonesome George here.

He lived to a ripe old age but failed, as they pointed out many times, to reproduce. Just recently, in 2012, he died, and with him the last of his species. He was couriered to the American Museum of Natural History and taxidermied there. A couple weeks ago his body was unveiled. This was the unveiling that I attended, and at this exact moment in time I can say that I was feeling a little like I am now: nervous and kind of nauseous, while everyone else seemed calm. I wasn’t prepared to see Lonesome George. Here he is taxidermied, looking out over Central Park, which was strange as well. At that moment realized that I knew the last individual of this species to go extinct. That presents this strange predicament for us to be in in the 21st century—this idea of conspicuous extinction. ...

JENNIFER JACQUET is Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, NYU; Researching cooperation and the tragedy of the commons; Author, Is Shame Necessary? Jennifer Jacquet's Edge Bio Page

... A strange thing happened on the way to a better world in pursuit of an admirable quest, that is, a world free of sex discrimination where you’re j

... A strange thing happened on the way to a better world in pursuit of an admirable quest, that is, a world free of sex discrimination where you’re j

What I wanted to talk about is somewhat of a parallel of that in human populations. If you were to go to a textbook on human biology from the time of Darwin or a bit later, you would certainly get an image that looked a bit like this. This is an image of the so-called races of humankind—racial types, as they called them. I’m not going to go into the question of whether there are real races of humankind because there aren’t. It’s interesting to note that until quite recently people assumed, and scientists assumed too, that the human species was divided into distinct groups that were biologically different from each other and had been isolated from each other for a long, long time.

Well, to some extent that was true. Until quite recently, human populations were isolated from each other. That’s changing quite quickly. ...

STEVE JONES is an Emeritus Professor of Genetics at University College London. Steve Jones's Edge Bio Page

MOLLY CROCKETT is an Associate Professor in the Department of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford; Wellcome Trust Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging. Molly Crockett's Edge Bio Page

MOLLY CROCKETT is an Associate Professor in the Department of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford; Wellcome Trust Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging. Molly Crockett's Edge Bio Page

HANS ULRICH OBRIST is the Co-director of the Serpentine Gallery in London; Author, Ways of Curating. Hans Ulrich Obrist's Edge Bio Page

JOHN BROCKMAN is the Editor and Publisher of Edge.org; Chairman of Brockman, Inc.; Author, By the Late John Brockman, The Third Culture. John Brockman's Edge Bio Page

[Continue to Part II — Video & Text]

EDGE & SERPENTINE GALLERY

Previous Edge-Serpentine collaborations have included:

"Formulae for the 21st Century" (2007)

"The Table-Top Experiment Marathon" (2007)

"Maps For The 21st Century" (2010)

"Information Gardens" (2011)

SPEAKING OF EXTINCTIONS....

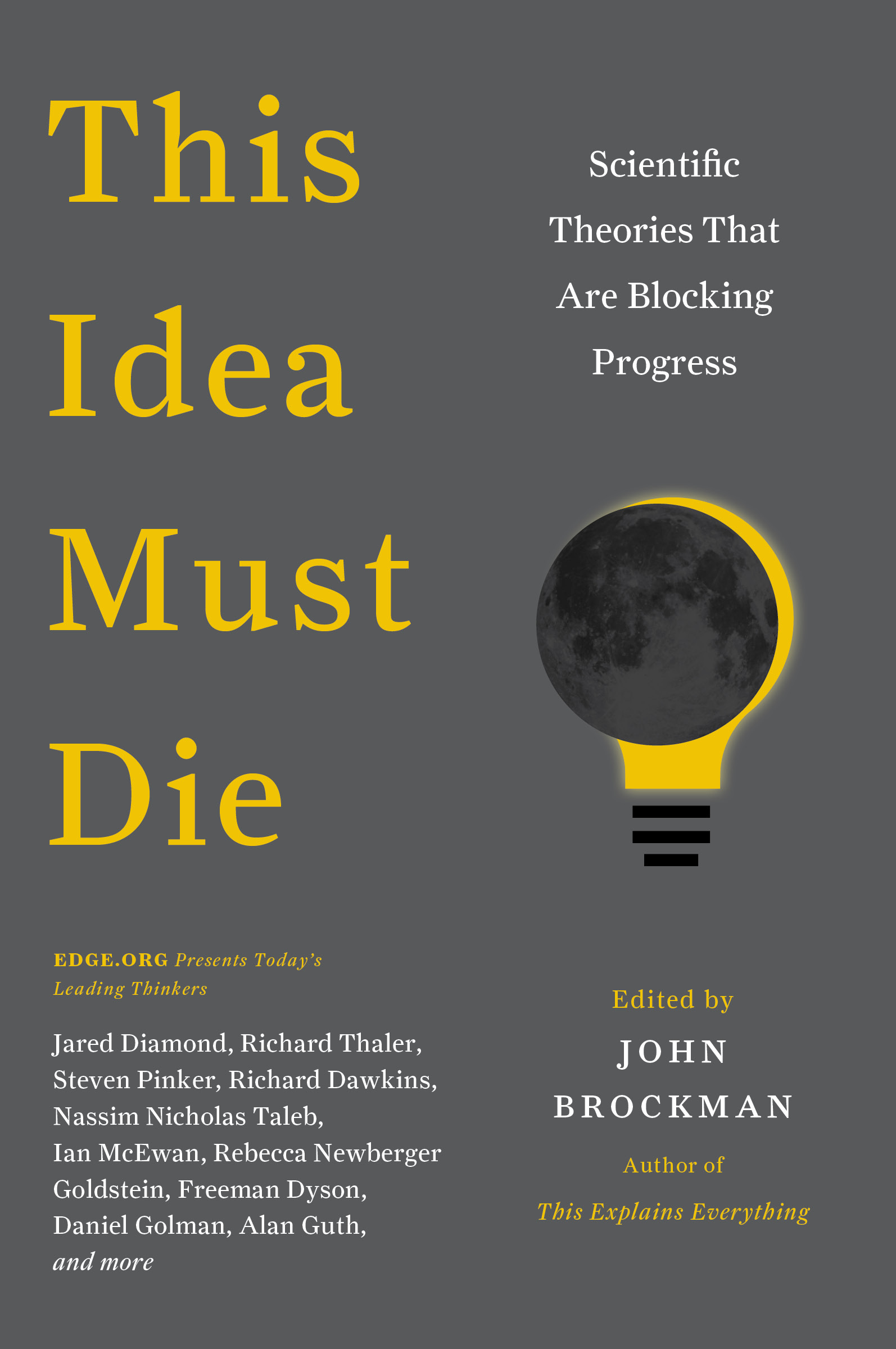

Edge's own contribution to the conversation will be published in February:

On the road to Munich in January for DLD14, the 10th annual DLD conference (Digital-Life-Day) run by Steffi Czerny and Lukas Kubina for Hubert Burda Media. The theme this year: "Content and Context." It was the fifth time Edge has been asked to participate. (See below for links to our previous DLD co-events.)

Steffi Czerny and John Brockman

This year the Edge conversation was on "information" from the Neandertal DNA sequenced by Svante Pääbo, the founder of the field of ancient DNA, to the multi-particle entanglement states of physicist Anton Zeilinger, which have become essential in fundamental tests of quantum mechanics and in quantum information science, most notably in quantum computation. In addition, Edge's roving editor, Jennifer Jacquet, was present for a session on "Time's Role in the Tragedy of the Commons" in which she developed themes in her work recently presented on Edge.

Svante Pääbo, Anton Zeilinger, John Brockman: On Information

Information is the foundation of our universe—and life itself. Cultural impresario John Brockman hosts a Third Culture conversation, spanning science and the humanities.

SVANTE PÄÄBO the founder of the field of ancient DNA, is Director, Department of Genetics, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig. Among his achievements are the first demonstration of DNA survival in an ancient Egyptian mummy, the first amplification of ancient DNA, the first study of the DNA from the Iceman found in the Alps, and the first retrieval of DNA from a Neanderthal in 1997. Four years ago, he initiated and organized an effort to sequence the entire Neanderthal genome. The first scientific overview of the genome was published in 2009 and was front page news wordwide. He is the author of Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes. Svante Pääbo's Edge Bio Page

ANTON ZEILINGER, a physicist, is Professor of Physics at the Quantum Optics, Quantum Nanophysics, Quantum Information Institute of University of Vienna. He is President of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the author of Dance of the Photons: From Einstein to Quantum Teleportation. Zeilinger is a pioneer in the field of quantum information and of the foundations of quantum mechanics. He realized many important quantum information protocols for the first time, including quantum teleportation of an independent qubit, entanglement swapping (i.e. the teleportation of an entangled state), hyper-dense coding (which was the first entanglement-based protocol ever realized in experiment), entanglement-based quantum cryptography, one-way quantum computation and blind quantum computation. His further contributions to the experimental and conceptual foundations of quantum mechanics include multi-particle entanglement and matter wave interference all the way from neutrons via atoms to macromolecules such as fullerenes. Anton Zeilinger's Edge Bio Page

Jennifer Jacquet: Times Role in the Tragedy of the Commons

How do tensions between individuals and groups play out? Between high-consuming people and low? Between the now and the future? Game theory offers answers.

JENNIFER JACQUET is Clinical Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies, NYU, researching shame, cooperation and the tragedy of the commons. She is also Edge's Roving Editor (see interviews with Adam Alter and Joseph Heinrich).

Her work was recently featured on Edge after Nature Climate Change published a study by Jacquet and her colleagues at two Max Planck Institutes on "Delayed Gratification Hurts Cimate Change Cooperation". Jennifer Jacquet's Edge Bio Page

EDGE @DLD: 2011: AN EDGE CONVERSATION IN MUNICH with Stewart Brand, George Dyson, Kevin Kelly, introduced by Andrian Kreye. A session with three of the original members of Edge who year in and year out provide the core sounding board for the ideas and information we present to the public. I refer to them in private correspondance as "The Council." Every year, beginning late summer, I consult with Stewart Brand, Kevin Kelly, and George Dyson, and together we create the Edge Annual Question which Edge has been asking since 1996. 2010: "INFORMAVORE" with Frank Schirrmacher, Editor of the Feuilleton and Co-Publisher of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Andrian Kreye, Feuilleton Editor of Sueddeutsche Zeitung, Munich; and Yale computer science visionary David Gelernter, who, in his 1991 book Mirror Worlds presented what's now called "cloud computing." 2009: REFLECTIONS ON A CRISIS: Daniel Kahneman, the greatest living psychologist, and Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the foremost scholar of extreme events discuss hindsight biases, the illusion of patterns, perception of risk, and denial. 2008: LIFE: A GENE-CENTRIC VIEW: Richard Dawkins & J. Craig Venter. It's not everyday you have Richard Dawkins and Craig Venter on a stage talking for an hour. That it occured in Germany, where the culture had been resistant to open discussion of genetics, and at DLD, the Digital, Life, Design conference organized by Hubert Burda Media in Munich, a high-level event for the digital elite—the movers and shakers of the Internet—made the discussion particularly interesting.

You can answer the question, but are you bright enough to ask it?

INTRODUCTION

by John Brockman

The Edge motto, adopted from the artist James Lee Byars' "World Question Center" is: "To arrive at the edge of the world's knowledge, seek out the most complex and sophisticated minds, put them in a room together, and have them ask each other the questions they are asking themselves." As Wallace Stevens wrote in "Notes Toward A Supreme Fiction" (1942): "The final elegance, not to console / Nor sanctify, but plainly to propound."

It's the quality of the questions that defines the scientific endeavor, not the answers encrusted in stories and narratives. This year, at SciFoo 2013, Edge presented the opportunity to several of the nearly 300 participants to respond to the following: "What is your question from SciFoo 2013?" Watch the 8-minute video below for the responses. This is followed by responses to the question "Who and/or what was fresh and new at SciFoo 2013?", and a photo gallery, which extends to San Francisco the following evening.

But first, what is "SciFoo"?

The annual event is run by three sponsors: O'Reilly Media (Tim O'Reilly is responsible for "FOO," or, "friends of O'Reilly"), Nature magazine (and their spin-off company, Digital Science), and Google. This year 62% of the participants were new. This approach keeps the event new and fresh every year. The ratio of participants to interesting people? 1-to-1.

As theoretical physicist and Nobel Laureate Frank Wilczek noted in his report on SciFoo 2007 for Edge:

"SciFoo is a conference like no other. It brings together a mad mix from the worlds of science, technology, and other branches of the ineffable Third Culture at the Google campus in Mountain View. Improvised, loose, massively parallel—it's a happening. If you're not overwhelmed by the rush of ideas then you're not paying attention."

Also, see George Dyson's report on SciFoo 2007; Photos and comments on SciFoo 2009, and the Edge-SciFoo report on SciFoo 2011.

Tyler Cowen, Joseph "Yossi" Vardi, Carl Page, Fiery Cushman, Lee Smolin, Linda Stone, Paul Davies, Paul Steinhardt, Peter Norvig, Richard Potts, Steve Fuller, Stuart Firestein

WHO AND/OR WHAT WAS FRESH AND NEW AT SCI/FOO 2013?

George Dyson, Esther Dyson, Steve Fuller, Stewart Brand, Paul Saffo, Coco Krumme, John Coates

A fascinating weekend, with one lingering regret—that I missed Rory Wilson’s talk on the use of accelerometers in free living animals. I had to piece together the gist of his talk from scraps given me by others and, fortunately, by Rory himself. In his work as an animal behaviorist Rory has been using actigraphy and accelerometers attached to animals in the wild in order to monitor continuously their energy expenditure. Beyond this, though, the data Rory has collected has uncovered subtle changes in background movement that actually reflect the animal’s motivational state. This finding is tremendously interesting. As we learn more about the brain, the more we see that it is built primarily to plan and execute movement, that activities we—under the influence of our Platonic heritage—commonly viewed as pure thought in fact have a somatic echo. Some scientists working with actigraphy have even found predictors, tremors if you will, of impending neuro-degenerative disease. But background activity changes that may reflect motivational states? The very possibility should tantalize any behavioural scientist.

Serendipity was at work this weekend: I met perhaps the only other person at scifoo (on the entire googolplex?) with a dumb phone. I stubbornly hold onto mine for the very purpose of serendipity, to dampen distraction. Ziyad Marar and I had a wonderful conversation about habits and human behavior, and soon discovered we have in common 1999-era telephones, as well as a healthy skepticism of social media. I hadn't heard of Ziyad's books (Happiness Paradox, Deception, Intimacy), but I picked up two at scifoo and couldn't put them down: his writing mulls human nature, weaving in literature and philosophy without succumbing to the tired conventions of contemporary science writing. A breath of fresh air.

PAUL SAFFO: Kröpelin's Mysteries of the Sahara

The single most astonishing session for me was Stefan Kröpelin's "Miracle of the Sahara." Kroplin compressed 40 years of research and exploration into a whirlwind tour of the Sahara's mysteries and what it is like to do science there. Summarizing conditions, he noted, "Sometimes, you get stuck hundreds of times per day… and the real problem isn't the heat; it's the cold." The size of the U.S, Kröpelin's Sahara is full of mysteries: Gilf Kebir, a sand plateau atop an ancient fluvial system in Southwest Egypt holds rock art from the middle Holocene, over 10,000 figures in one cave alone. The Wadi Howar was thought by Heroditus to be the source of the Nile; now it is vast desert, but in it's heart is the Ounianga Kebir, a cluster of freshwater aquifer-fed "gravity lakes," and home to seven crocodiles, the remnant of an Ice Age population, now isolated from other crocs by hundreds of miles of searing desert.

But the biggest mystery was sitting right in front of Kröpelin as he spoke. It was a chunk of "Libyan Desert Glass," 28 million year-old fused glass the color of pale emerald and the purest natural glass in the world. Discovered by Europeans in 1932, the stuff is strewn across a vast area of desert at the edge of Egypt's great Sand Sea. Kröpelin's chunk looked like a glass meteorite, complete with ablation regmaglypts, suggesting that the glass was created by a meteor strike that liquefied the surface rocks in a process not unlike that which created tektite strewn-fields elsewhere on the earth. Except… no one has found a crater. Perhaps the glass is a radiative melt artifact of a Tunguska-like airburst? Others speculate that it is hydrovolcanic in origin, but no has found a volcanic source.

What we do know is that the Sahara's earliest inhabitants knapped the glass into tools, and that it was prized by the Egyptians—a scarab carved from the stuff is set into a pectoral worn by Tutankhamun. That fact tied nicely with Kröpelin's final and most surprising statement: the origins of the pharonic tradition lie in the Western Desert, not the Nile Valley. And if the Egyptian civilization was born from the Sahara, then by association, Europe's roots are hidden there as well.

STEWART BRAND: What if climate change is good for civilization?

(If it is, it would completely invalidate the first chapter of my Whole Earth Discipline, which spells out how climate change is an apocalypse-in-waiting for civilization. My personal mantra tries to be: "Every day I wonder how many things I am dead wrong about." This might be one of them.)

Climate change apparently ignited civilization in Egypt, said Stefan Kröpelin in a small, intense session at SciFoo. His four decades of insanely adventurous researches in the eastern Sahara—where no one goes—show that people lived all over that region when it was a rich savanna filled with game, before 8,000 years ago. In those centuries people avoided the Nile, which was dangerous with floods and fearsome animals.

In the period 5300-3500 BCE the Sahara gradually but relentlessly dried up. The people from the desert were forced to take on the Nile, first for farming, soon for a river-taming civilization of such durability that it eventually inspired Greece, Rome, and Europe.

Climate change made it happen. The evidence is in the sumptuous cave art at Wadi Sura and the silt of the astonishingly ancient Ounianga Lakes.

What is our unthinkably dangerous Nile that climate change might force us to take on? What abilities might we be forced to acquire?

STEVE FULLER: How must we re-orient ourselves to make the most out of seasteading?

At Sci Foo Camp 2013, David Ewing Duncan and Linda Avey presented a very persuasive case for an indefinite expansion of 'seasteading', a term that I had learned about from Duncan in an earlier session on cognitive and moral enhancement by neuroscientific means. I had been already familiar with Peter Thiel's support for a ship floating just beyond US territorial waters near San Francisco Bay that enabled innovators lacking US citizenship to conduct research outside the gaze of American regulators. However, the session enabled me to see that seasteading, far from being a strategy for avoiding inconvenient forms of regulation, on the contrary might be something that states themselves encourage—though perhaps indirectly, depending on the political climate. However, this proposal would make policy sense only on the following condition: The outcomes of the research conducted in these 'ethics-free' zones would have to be made public, with the understanding that no one would be prosecuted, no matter how bad the outcomes are perceived to have been. In other words, we would need to become sufficiently mature to accept the admission of error in pursuit of a good cause as adequate punishment in itself.

The most wonderful session I attended—and the most meaningful experience overall—was Michael Chorost talking about his own cochlear implant. It was what science really is—the response to curiosity. He told us how it worked, played recordings so we could get some sense of how things sound to people who have an implant. He passed some samples around the room for us to touch and examine. We talked about learning to hear—and how there's a point in childhood after which it gets harder and harder to learn. We got an understanding of the technology, and also of how the technology changes both individual lives and cultural norms—such as sign language, which may become the language of the poor deaf as the rich deaf start using cochlear implants. In theory they can be covered by Medicare, but somehow the rich seem to get them and the poor don't... Is that right?

Is there something similar coming for vision? (Of course, this comment—and the session itsel —raises questions and doesn't answer them all; that's the point of SciFoo...)

This was SciFoo's seventh year, and, in era where the half-life of a conference is measured in years, not decades, it is holding up well. Tim O'Reilly (O'Reilly), Timo Hannay (Nature/Digital Science )and Chris DiBona (Google) have found a formula that works, and are sticking to it. Big Data, once the all-consuming subject, is now just another scientific instrument, like a space telescope or an electron microscope, and the excitement was back to the details of what you can do with it, now that you have it. And how do you encourage scientific thinking in children (and politicians)? Among the people who showed up from left field and stole the show (a regular occurrence at SciFoo) this year was Carmen Medina, who, in her own introductory words, "spent 32 years at the Central Intelligence Agency and decided early on that how we form opinions is much more interesting than any particular opinion. Passionate about empowering heretics in the workplace and attacking conventional wisdom. Believe we need entirely new construct for the concept of national security, perhaps abandoning it altogether. Convinced there is worldwide conspiracy for preservation of Mediocrity." Amen!

A number of Edge contributors were among the speakers at the recent TED conference (TED 2010) in Long Beach: Stewart Brand,Nicholas Christakis, George Church, Denis Dutton, Sam Harris, Daniel Kahneman, Benoit Mandelbrot, Nathan Myhrvold, Michael Shermer, and even one of the first speakers at the Reality Club of the early 80s, Stephen Wolfram. And many more individuals in the Edge community as well as friends were in attendance. Come, take a walk with me.

Below is a link to Daniel Kahneman's recently posted TED Talk — featuring the superb video production values that are becoming the hallmark of the TED Talks — along with links to Kahneman's relevant Edge contributions.

—JB

Edge was in Munich for DLD 2010 and an Edge/DLD event. The event, entitled "Informavore," is a discussion featuring Frank Schirrmacher, editor of the Feuilleton and co-publisher of Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung; Andrian Kreye, Feuilleton editor of Sueddeutsche Zeitung, Munich; and Yale computer science visionary David Gelernter, who, in his 1991 book Mirror Worlds presented what's now called "cloud computing."

Gelernter's June 2000 manifesto, published by both Edge and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, was at the time widely read and debated. In it, he famously wrote: "Everything is up for grabs. Everything will change. There is a magnificent sweep of intellectual landscape right in front of us."

|

|

|

|

FURTHER READING ON EDGE:

The Age of the Informavore: A Talk with Frank Schirrmacher

Lord of the Cloud: John Markoff and Clay Shirky talk to David Gelernter

"The Second Coming: A Manifesto" by David Gelernter

The Edge Annual Question 2010: How Is The Internet Changing the Way You Think?

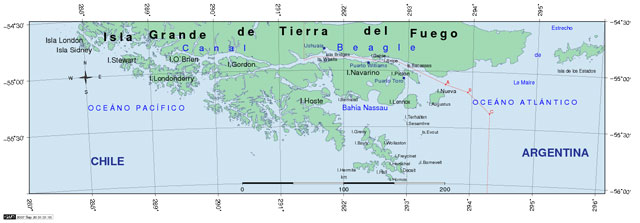

Edge was invited by Alvaro Fischer, the Director of Fundacion Ciencia Y Evolucion in Chile to attend the Foundation's Darwin Seminar in Santiago, entitled "Darwin's Intellectual Legacy To The 21st Century" and join the eight speakers (all Edge contributors) on a trip to the "extreme south" including a trip along "The Beagle Channel", named after the ship HMS Beagle which surveyed the coasts of the southern part of South America from 1826 to 1830.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Seminar, which ran for two days, attracted an audience of 2,200 people on each day...

"Our intention is to illuminate and discuss how Darwinian thought influenced the disciplines that focus on the study the individuals (biology, neuroscience, psychology); the individual within their social interactions (anthropology, sociology, economy, political science); and how these concepts pertain, in general, to a moral philosophy."

Ian McEwan Steven Pinker Matt Ridley John Tooby

"We wish to explore how, from Darwinian thought, there emerges a vision of what it is to be a human being. And that this vision is fundamental and coherent with the entire body of accumulated scientific knowledge. With reverence for the details of their application, it is the impact of Darwin's ideas that is the reason we are celebrating Darwin's anniversary."

After the Seminar, the Foundation flew the group to Tierra del Fuego and The Beagle Channel, where we boarded the Chilean Navy Patrol boat SS Isaza at 6am at Puerto Williams the next day for a 19-hour trip to "the end of the world". Charles Darwin, on the second trip of HMS Beagle under Captain Robert FitzRoy, wrote in his field notebook in 1833, "many glaciers beryl blue most beautiful contrasted with snow".

As part of our celebration the three hundredth edition of Edge, we are pleased to present a video record (with accompanying slides) of the eight talks, a video interview with program organizer Alvaro Fischer, and a Photo Galleryof the trip.

— JB

Photo Credits: The Beagle Channel photographs on this page (and releated in the Photo Gallery) are by Steven Pinker. Images in the Photo Gallery are by Pilar Valenzuela (with the addition of the Pinker images and snapshots added by the speakers).

"Mountain In Glow of Sunrise Beagle Channel"

DARWIN'S INTELLECTUAL LEGACY TO THE 21ST CENTURY

A Talk With Alvaro Fischer

ALVARO FISCHER mathematical engineer, entrepreneur and businessman, is President of the Ciencia y Evolución Foundation, organizer of the 2009 seminars on Darwin’s Legacy to the XXI Century , member of the editorial committee of the El Mercurio newspaper, author of Evolution: The New Paradigm.

Further reading on Edge: "Why Chile?" by Alvaro Fischer

"Clouds Over Darwin Range"

Some people think today that it is impossible for a mindless process to produce evolution. ... It isn't. ...There may be an intelligent God hidden in the evolution process, but if so, he might as well be asleep, since there is no work for him to do!

DARWIN AND THE EVOLUTION OF REASONS

DANIEL C. DENNETT is a philosopher; University Professor, Co-Director, Center for Cognitive Studies, Tufts University; Author, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon

"Buff Necked Ibises In Flight"

There's a mismatch between the modern versus ancestral world. Our minds are equipped with programs that were evolved to navigate a small world of relatives, friends, and neighbors, not for cities and nation states of thousands or millions of anonymous people. Certain laws and institutions satisfy the moral intuitions these programs generate. But because these programs are now operating outside the envelope of environments for which they were designed, laws that satisfy the moral intuitions they generate may regularly fail to produce the outcomes we desire and anticipate that have the consequences we wish. ...

EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY Cognitive instincts for cooperation, institutions & society

LEDA COSMIDES, is the founder of the field of Evolutionary Psychology. She is he co-director of UCSB's Center for Evolutionary Psychology.

"Chilean Armada Ship PSG Isaza"

The modern social sciences are built on an Aristotlean blank slate foundation. On the Aristotlean view the mind is like a tape recorder or video recorder assumes: the mechanisms of recording (learning) do not impart any content of their own to the signal that it absorbs our mental content is therefore wholly supplied by the senses, especially from social sources (culture). Basing the social sciences on the mistaken theory that the mind is like a blank slate was a fundamental error that has kept the social sciences from being as fully successful as the natural sciences.

THE EVOLUTIONARY APPROACH TO THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

By John Tooby

JOHN TOOBY is the founder of the field of Evolutionary Psychology. He is he co-director of UCSB's Center for Evolutionary Psychology.

"Island Clouds and Mountains"

Language is an adaptation to the "cognitive niche". It facilitates exchange of information, negotiating of cooperation. But indirect speech (polite requests, veiled threats & bribes, sexual overtures) are a puzzle for the theory that language is an adaptation for efficient communication. Language is an adaptation to the "cognitive niche". ...

STEVEN PINKER is a Harvard College Professor and Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology, Harvard University; Author, The Stuff of Thought.

"Upland Goose In Flight"

Farming — a division of labour between humans and other species; Fossil fuels — a division of labour between humans and extinct species?

PARALLELS BETWEEN ECONOMICS AND EVOLUTION, OR — WHAT HAPPENS WHEN IDEAS HAVE SEX

By Matt Ridley

MATT RIDLEY is a Science Writer; Founding chairman of the International Centre for Life; Author, Francis Crick: Discoverer of the Genetic Code.

Further reading on Edge: "The Genome Changes Everything": A Talk with Matt Ridley

"Dramatic Sky Beagle Channel"

If we want to change the world, we need first to understand it. And when it comes to understanding human nature — male and female — Darwinian science is indispensable.

WHY SEX DIFFERENCES MATTER: THE DARWINIAN PERSPECTIVE

HELENA CRONIN launched and runs Darwin@LSE. She is a Co-Director of LSE's Centre for Philosophy of Natural and Social Science. Author,The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection from Darwin to Today.

Further reading on Edge:"Getting Human Nature Right": A Talk with Helena Cronin

"Blue-Eyed Comorant In Flight"

...I want to engage you in a discussion of the deep history of beauty. By deep I mean as seen from an evolutionary perspective. I am an "evolutionary psychologist". I believe that to understand and fully appreciate human mental traits, we need to know why they are there — which is to say what biological function they are serving. Evolutionary psychology has been making pretty good progress. But, as we say, "there are still some elephants in the living room" — big issues that no one wants to talk about. And human beings worship of the beautiful remains one of the biggest.

BEAUTY’S CHILD: SEXUAL SELECTION, NATURE WORSHIP AND THE LOVE OF GOD

NICHOLAS HUMPHREY is Professor Emeritus, London School of Economics and author of Seeing Red: A Study in Consciousness.

"Fuquet Glacier Face"

I'm going to talk about some convergences, about arts and science, as far apart as science and religion, two magisteria, if you might say, and yet at some human level they converge.

ON BEING ORIGINAL IN SCIENCE AND IN ART

By Ian McEwan

IAN MCEWAN, novelist, is the author of On Chesil Beach.

"Soft Light Beagle Channel"

REFLECTIONS ON A CRISIS

Daniel Kahneman & Nassim Nicholas Taleb: A Conversation in Munich

(Moderator: John Brockman)

View the complete 1-hour HD streaming video of the Edge event that took place at Hubert Burda Media's Digital Life Design Conference (DLD) in Munich on January 27th as the greatest living psychologist and the foremost scholar of extreme events discuss hindsight biases, the illusion of patterns, perception of risk, and denial.

DANIEL KAHNEMAN is Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology, Princeton University, and Professor of Public Affairs, Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. He is winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for his pioneering work integrating insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty. Daniel Kahneman's Edge Bio Page

NASSIM NICHOLAS TALEB, essayist and former mathematical trader, is Distinguished Professor of Risk Engineering at New York University’s Polytechnic Institute. He is the author of Fooled by Randomness and the international bestseller The Black Swan. Nassim Taleb's Edge Bio Page

FOCUS ONLINE

January 28, 2009

ARE BANKERS CHARLATANS

At blame for the financial crisis is the nature of man, say two renowned scientists: Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman and bestselling author Nassim Taleb ( "The Black Swan").

By Ansgar Siemens, FOCUS online editor

Two men sitting on the stage. Left. Daniel Kahneman, 74, bright-eyed, Nobel Prize winner. Right Nassim Taleb, 49, former Wall Street banker, best-selling author. Both speak on the future of Digital Life Design Conference (DLD) in Munich on the financial crisis, about the beginning--mainly they talk about people. They say it is due to human nature, that the crisis has broken out. And they choose harsh words in discussing the scale of the disaster.

Kahneman explains why there are bubbles in the financial markets, even though everyone knows that they eventually burst. The researchers used the comparison with the weather: If there is little rain for three years, people begin to believe that this is the normal situation. If over the years stocks only increase, people can't imagine a break in this trend.

"Those responsible must go--today and not tomorrow"

Taleb speaks out sharply against the bankers. The people in control of taxpayer's money are spending billions of dollars. "I want those responsible for the crisis gone today, today and not tomorrow," he says, leaning forward vigorously. The risk models of banks are a plague, he says, the bankers are charlatans.

It is nonsense to think that we can assess risks and thus protect against a crash. Taleb has become famous with his theory of the black swan described in his eponymous bestsellers described. Black swans, which are events that are not previously seen--not even with the best model. "People will never be able to control a coincidence," he says.

The early warning

"Taleb had an early warning before the crisis. In 2003 he took note of the balance sheet of the U.S. mortgage finance giant Fannie Mae, and he saw "dynamite".

In autumn last year, the U.S. government instituted A dramatic bailout. Taleb said in the "Sunday Times" in 2008: "Bankers are very dangerous." And even now, he sees a scandal: He provocatively asks what have the banks done with the government bailout money. "They have paid out more bonuses, and they have increased their risks." And it was not their own money.

Taleb calls for rigorous changes: nationalize banks--and abolish financial models. Kahneman does not quite agree with him. Certainly, the models are not capable of predicting a collapse. But one should not ignore our human nature. People will always require and use models and get benefit from them--even if they are wrong.

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

CHANGING LIFESTYLE CHANGES GENE EXPRESSION Founder and president of the non-profit Preventive Medicine Research Institute

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

LIFE IS THE WAY THE ANIMAL IS IN THE WORLD Professor of Philosophy at the University of California; Author, Out of Our Heads

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

A RULE OF THE GAME Curator, Serpentine Gallery, London; Editor: A Brief History of Curating; Formulas for Now

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

EDGE MASTER CLASS 2008 |

|||

|

|

|||

|

IMPROVING CHOICES WITH MACHINE READABLE DISCLOSURE (CLASS 2) THALER: Father of Behavioral Economics; Director, Center for Decision Research, University of Chicago Graduate School of Business; Co-Author, Nudge At a minimum, what we're saying is that in every market where there is now required written disclosure, you have to give the same information electronically and we think intelligently how best to do that. In a sentence that's the nature of the proposal.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF SCARCITY (CLASS 3) Professor of Economics at Harvard Nathan Myhrvold, Richard Thaler, Daniel Kahneman, France LeClerc, Danny Hillis, Paul Romer, George Dyson, Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Sean Parker Let's put aside poverty alleviation for a second, and let's ask, "Is there something intrinsic to poverty that has value and that is worth studying in and of itself?" One of the reasons that is the case is that, purely aside from magic bullets, we need to understand are there unifying principles under conditions of scarcity that can help us understand behavior and to craft intervention. If we feel that conditions of scarcity evoke certain psychology, then that, not to mention pure scientific interest, will affect a vast majority of interventions. It's an important and old question. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

TWO BIG THINGS HAPPENING IN PSYCHOLOGY TODAY (CLASS 4) Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology; Author, Thinking Fast and Slow

There's new technology emerging from behavioral economics and we are just starting to make use of that. I thought the input of psychology into economics was finished but clearly it's not! THE REALITY CLUB W. Daniel Hillis, Daniel Kahneman, Nathan Myhrvold, Richard Thaler on "Two Big Things Happening In Psychology Today" |

|||

|

|

|||

|

THE IRONY OF POVERTY (CLASS 5) Professor of Economics at Harvard I want to close a loop, which I'm calling "The Irony of Poverty." On the one hand, lack of slack tells us the poor must make higher quality decisions because they don't have slack to help buffer them with things. But even though they have to supply higher quality decisions, they're in a worse position to supply them because they

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

MODELING THE FUTURE Climatologist, is a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences Warming is unequivocal, that's true. But that's not a sophisticated question. A much more sophisticated question is how much of the climate Ma Earth, a perverse lady, gives us is from her, and how much is caused by us. That's a much more sophisticated, and much more difficult question. |

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

ANTS HAVE ALGORITHMS Assistant Professor, Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University

|

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

SOCIAL NETWORKS ARE LIKE THE EYE Physician and Social Scientist, Harvard University; Coauthor, Connected: The Surprising Power of Our Social Networks and How They Shape Our Lives

|

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

ENGINEERING BIOLOGY Assistant Professor of Bioengineering, Stanford University

|

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

THE IMPLICIT ASSOCIATION TEST ANTHONY GREENWALD is Professor of Psychology at University of Washington MAHZARIN BANAJI Psychologist; Richard Clarke Cabot Professor of Social Ethics, Department of Psychology, Harvard University

"The IAT provides a useful window into some otherwise difficult-to-detect contents of our minds. It may be "an inconvenient truth" that what's there is not what we thought was there or want to be there. But I think it is generally something we can come to grips with." — Anthony Greenwald |

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE MASTER CLASS 2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology; Author, Thinking Fast and Slow

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology; Author, Thinking Fast and Slow

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology; Author, Thinking Fast and Slow

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology; Author, Thinking Fast and Slow

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology; Author, Thinking Fast and Slow

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eugene Higgins Professor of Psychology; Author, Thinking Fast and Slow

|

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE SEMINAR 2007 |

|

|

|

|

|

LIFE: WHAT A CONCEPT! Professor of Physics, Institute for Advanced Study; Author, Many Colored Glass; The Scientist as Rebel

|

|

|

|

|

|

LIFE: WHAT A CONCEPT! Professor, Harvard University, Director, Personal Genome Project

|

|

|

|

|

|

LIFE: WHAT A CONCEPT! Leading scientist of the 21st century for Genomic Sciences; Co-Founder, Chairman, CEO, Co-Chief Scientific Officer, Synthetic Genomics, Inc.; Founder, President and Chairman of the J. Craig Venter Institute; author, A Life Decoded We're just at the tip of the iceberg of what the divergence is on this planet. We are in a linear phase of gene discovery maybe in a linear phase of unique biological entities if you call those species, discovery, and I think eventually we can have databases that represent the gene repertoire of our planet. |

|

|

|

|

|

LIFE WHAT A CONCEPT Professor Emeritus of Chemistry and Senior Research Scientist, New York University; Author, Planetary Dreams

|

|

|

|

|

|

LIFE: WHAT A CONCEPT! Professor of Astronomy, Harvard University; Director, Harvard Origins of Life Initiative

|

|

|

|

|

|

LIFE: WHAT A CONCEPT! Professor of Quantum Mechanical Engineering, MIT; Author, Programming the Universe

|

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

RECURSION AND HUMAN THOUGHT Linguistic Researcher; Dean of Arts and Sciences, Bentley University; Author, Language: The Cultural Tool

|

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION Professor of Evolutionary Developmental Biology, Imperial College; Author, Mutants

|

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

A COOPERATIVE FORAGING EXPERIMENT: LESSONS FROM ANTS Research Fellow in Evolutionary Biology, Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London

|

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

HOW OUR LIMBS ARE PATTERNED LIKE THE FRENCH FLAG Professor of Biology, University College London

|

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

SO WOMEN HAVE BETTER EMPATHY THAN MEN? Psychologist, Autism Research Centre, Cambridge University; Author, Zero Degrees of Empathy

"It turns out that when you test newborn babies—this experiment was done at the age of 24 hours old, where we had 100 babies who were tested looking at two kinds of objects—a human face and a mechanical mobile. And they were filmed for how long they looked at each of these two objects. What you can see here is that on the first day of life, we had more boys than girls looking for longer at the mechanical mobile and more girls than boys looking at the face. So you can see that these differences when they emerge, first of all they seem to emerge very early—at birth—suggesting that there may be a biological component to a sex difference in, in this case, interest in faces; and secondly, they don't apply to all males or all females, these differences emerge as statistical trends when you compare groups." |

|

|

|

|

|

EDGE CONVERSATION

A FULL-FORCE STORM WITH GALE WINDS BLOWING Evolutionary Biologist; Professor of Anthropology and Biological Sciences, Rutgers University; Author, The Folly of Fools

|

Last year Edge received an invitation from Juan Insua, Director of Kosmpolis, a traditional literary festival in Barcelona, to stage an event at Kosmopolis 05 as part of an overall program "that ranges from the lasting light of Cervantes to the (ambiguous) crisis of the book format, from a literary mapping of Barcelona's Raval district to the dilemma raised by the influence of the Internet in the kitchen of writing, from the emergence of a new third culture humanism to the diverse practices that position literature at the core of urban creativity."

|

|

|

|

Eduard Punset — Redes-TV |

|

Click for information on "Darwin Y La Tercera Cultura" on Redes TV

Click here for a 2-minute tv clip

Las nuevas lecturas del 'Quijote' copan los actos de Kosmopolis

Israel Punzano — Barcelona

EL PAÍS - Cultura - 04-12-2005

Cervantes was not the the only protagonist of the second day of Kosmopolis. Also debated was the influence of Darwin's theory of the natural selection in the advances of diverse scientific disciplines, that include evolutionary biology to neuroscience to cosmology. In this colloquy, which also covered the future of the humanism, were the cosmologist Lee Smolin, the biologist Robert Trivers and the neurocientist Marc Hauser. The presentation of the event was Eduard Punset and the moderator was John Brockman, who is know for spreading scientific publications. Smolin emphasized the importance of the investigations of Darwin in the later development of Einstein's theory of the relativity and wondered if we were prepared to accept a world without absolute laws, where everything changes. Hauser pointed out that the revolution of Darwin's revolution was also about morality, as it counters the rationality of Kant and the predominance of emotions in Hume.

Brockman: "Hoy la cultura es la ciencia, los intelectuales de letras estan desfasados"

Justo Barranco — 05/12/2005 — Barcelona

"The thinkers of the third culture are the new public intellectuals" as "science is the only news"... "Nobody voted the electricity, the Internet, the birth control pill, or for fire. "The great inventions that change everything involves technology based on science "... "It is critical to participate in the discussion of such questions today as the culture is science."

TRIBUNA: JOHN BROCKMAN

La tercera cultura en Kosmopolis

John Brockman

EL PAÍS - 05-12-2005

In terms of science, the third culture is front and center: geneticist J. Craig Venter is attempting to create synthetic genes as an answer to our energy needs; biologist Robert Trivers is exploring the evolutionary basis for deceit and self-deception in human nature; biologist Ian Wilmut, who cloned Dolly the sheep, is using nuclear transfer to produce embryonic stem cells for research purposes and perhaps eventually as cures for disease; cosmologist Lee Smolin researches the Darwinian evolution of universes; quantum physicist Seth Lloyd is attempting to build quantum computers; psychologist Marc D. Hauser is examining our moral minds; and computer scientists Sergey Brin and Larry Page of Google are radically altering both the way we search for information, as well as the way we think.

CULTURA

Kosmopolis, literatura a la ultima

Eva Belmonte

December 3, 2005

Kosmopolis 2005. Celebration of International of Literature in the Center of Contemporanea Culture of Barcelona (CCCB).

...The relation between science and the third culture was another one of the subjects of debate of this Celebration of Literature. Four personalities of the scientific world participated in the Third Culture event. They are Robert Trivers, John Brockman, Marc Hauser and Lee Smolin. They demonstrated that Literature is not is not just the province of the old school of the humanities culture.

Can a person be considered cultured today with only slight knowledge of fields such as molecular biology, artificial intelligence, chaos theory, fractals, biodiversity, nanotechnology or the human genome? Can we construct a proposal of universal knowledge without such knowledge? The integration of "literary culture" and "scientific culture" is the basis for what some call the "third culture": a source of metaphors that renews not only the language, but also the conceptual tookit of classic humanism

Can a person be considered cultured today with only slight knowledge of fields such as molecular biology, artificial intelligence, chaos theory, fractals, biodiversity, nanotechnology or the human genome? Can we construct a proposal of universal knowledge without such knowledge? The integration of "literary culture" and "scientific culture" is the basis for what some call the "third culture": a source of metaphors that renews not only the language, but also the conceptual tookit of classic humanism

The New Humanists

SALVADOR PÁNIKER

A polifacética figure

Brockman and the New Intellectuals

Interview

"Science won the battle"

SALVADOR LLOPART

"¿Qué queda del marxismo? ¿Qué queda de Freud? La neurociencia le ha dejado como una superstición del siglo XVIII, de ideas irrelevantes"

...there is a deep relation between Einstein's notion that everything is just a network of relations and Darwin's notion because what is an ecological community but a network of individuals and species in relationship which evolve? There's no need in the modern way of talking about biology for any absolute concepts for any things that were always true and will always be true.—Lee Smolin

...what I'm interested in is how science can now come together with moral philosophy and do some interesting work at the overlap areas. This is not to say that science takes over philosophy, by no means. It works together with philosophy, to figure out what the deep issues are, what the overlapping areas are, and how we can meet together.—Marc D. Hauser

I believe that self-deception evolves in the service of deceit. That is, that the major function of self-deception is to better deceive others. Both make it harder for others to detect your deception, and also allow you to deceive with less immediate cognitive cost. So if I'm lying to you now about something you actually care about, you might pay attention to my shifty eyes if I'm consciously lying, or the quality of my voice, or some other behavioral cue that's associated with conscious knowledge of deception and nervousness about being detected. But if I'm unaware of the fact that I'm lying to you, those avenues of detection will be unavailable to you. —Robert Trivers

TRIVERS, SMOLIN, HAUSER,: "DARWIN Y LA TERCERA CULTURA" IN BARCELONA

Last year Edge received an invitation from Juan Insua, Director of Kosmpolis, a traditional literary festival in Barcelona, to stage an event at Kosmopolis 05 as part of an overall program "that ranges from the lasting light of Cervantes to the (ambiguous) crisis of the book format, from a literary mapping of Barcelona's Raval district to the dilemma raised by the influence of the Internet in the kitchen of writing, from the emergence of a new third culture humanism to the diverse practices that position literature at the core of urban creativity."

Last year Edge received an invitation from Juan Insua, Director of Kosmpolis, a traditional literary festival in Barcelona, to stage an event at Kosmopolis 05 as part of an overall program "that ranges from the lasting light of Cervantes to the (ambiguous) crisis of the book format, from a literary mapping of Barcelona's Raval district to the dilemma raised by the influence of the Internet in the kitchen of writing, from the emergence of a new third culture humanism to the diverse practices that position literature at the core of urban creativity."

Something radically new is in the air: new ways of understanding physical systems, new focuses that lead to our questioning of many of our foundations. A realistic biology of the mind, advances in physics, information technology, genetics, neurobiology, engineering, the chemistry of materials: all are questions of capital importance with respect to what it means to be human.

Charles Darwin's ideas on evolution through natural selection are central to many of these scientific advances. Lee Smolin, a theoretical physicist, Marc D. Hauser, a cognitive neuroscientist, and Robert Trivers, an evolutionary biologist, travelled to Barcelona last October to explain how the common thread of Darwinian evolution has led them to new advances in their respective fields.

The evening was presented by Eduard Punset, host of the internationally-viewed Spanish-language science television program Redes, and a best-selling author in Spain. A Redes television program based on the event was broadcast throughout Spain and Latin America.

The house was packed. The Barcelona press was present (see El Pais, La Vanguardia, El Pais, El Mundo, and a cover story in "Culturas", the magazine fo La Vanguardia).

I believe that self-deception evolves in the service of deceit. That is, that the major function of self-deception is to better deceive others. Both make it harder for others to detect your deception, and also allow you to deceive with less immediate cognitive cost. So if I'm lying to you now about something you actually care about, you might pay attention to my shifty eyes if I'm consciously lying, or the quality of my voice, or some other behavioral cue that's associated with conscious knowledge of deception and nervousness about being detected. But if I'm unaware of the fact that I'm lying to you, those avenues of detection will be unavailable to you.

ROBERT TRIVERS: DECEIT AND SELF-DECEPTION

(ROBERT TRIVERS:) Why do I talk about, or wish to talk about, deception and self-deception in the same breath? Because I think you miss the truth about each if you are not conscious of the other and the relationship between the two. If by deception you only think of conscious deception, where you're planning to lie or aware of the fact that you're lying, you will miss all the lying that goes on that the individual is unaware of, and this may be the larger portion of lies and deception that is going on.

Conversely, if you think about self-deception without comprehending its connection with deception, then I think you'll miss the major function of self-deception. In particular, you'll be tempted to go the route that psychology went a hundred years ago or so and think of self-deception as defensive: I'm defending my tender ego, I'm defending my weak psyche. And you will not see the offensive characteristic of self-deception.

What do I mean by that? I mean that I believe that self-deception evolves in the service of deceit. That is, that the major function of self-deception is to better deceive others. Both make it harder for others to detect your deception, and also allow you to deceive with less immediate cognitive cost. So if I'm lying to you now about something you actually care about, you might pay attention to my shifty eyes if I'm consciously lying, or the quality of my voice, or some other behavioral cue that's associated with conscious knowledge of deception and nervousness about being detected. But if I'm unaware of the fact that I'm lying to you, those avenues of detection will be unavailable to you.

What do I mean by that? I mean that I believe that self-deception evolves in the service of deceit. That is, that the major function of self-deception is to better deceive others. Both make it harder for others to detect your deception, and also allow you to deceive with less immediate cognitive cost. So if I'm lying to you now about something you actually care about, you might pay attention to my shifty eyes if I'm consciously lying, or the quality of my voice, or some other behavioral cue that's associated with conscious knowledge of deception and nervousness about being detected. But if I'm unaware of the fact that I'm lying to you, those avenues of detection will be unavailable to you.

Regarding the second argument, it is intrinsically difficult, and mentally demanding, to lie and be conscious about it. The more complex in detail the lie—the longer you have to keep it up—the more costly cognitively. I believe that selection favors rendering a portion of the lie unconscious, or much of the knowledge of it unconscious, so as to reduce the immediate cognitive cost. That is, with self-deception you'll perform better cognitively on unrelated tasks that you might have to do moments later than if you had just undergone a lot of consciously mediated deception.

Let me step back and say a word or two about the underlying logic. First of all, we understand that if we are making an evolutionary argument in terms of natural selection, we are talking about benefits to individuals in terms of the propagation of their own genes, and there are innumerable opportunities in nature to gain a benefit by deceiving another.

However, the reverse is true for the deceived.

The deceived is typically losing knowledge or resources or whatever, resulting in a decrease in the propagation of their genes. So you have what we call a co-evolutionary struggle: with natural selection improving deception on the one hand, and improving the ability to spot deception on the other.

Now let me just say that deception is a very deep feature of nature. At all levels, all interactions, e.g. viruses and bacteria often use deception to get inside you. They may mimic your own cell surface proteins. They may have other tricks to deceive your system into not recognizing them as alien and worthy of attack. Even genes inside yourself, which propagate themselves selfishly during meiosis may do so by mimicking particular sub-sections of other genes so as to get copied an extra time, even though the rest of the genome, if you asked their opinion, would be against this extra copying.

When you turn to insects and larger creatures like those, we know that in relations between species, again there's a huge and rich world of deception. Considering insects alone: they will mimic harmless objects so as to avoid detection by their predators. Or they will mimic poisonous or distasteful objects to avoid being eaten. Or they will mimic a predator of their predator, so as to frighten away their predator. Or, in one case, they will mimic the predator that's trying to eat them, so that the predator misinterprets them as a member of their own species and gives them territorial display instead of eating them.

They will even, I have to tell you, mimic the feces, or droppings, of their predators. That's so common it has a technical term in the literature, forgive me, "shit mimics". And they come in all varieties and sizes. There are moths that look like the splash variety of a bird dropping. And you can understand from the bird's standpoint, you might have a strong supposition that this is a butterfly or a moth, but you'd be unwilling to put it to the test—especially if you have to use your beak to put it to a test.

Now when you turn to relations within species, you find a rich world that we're uncovering now of deception also. To give you two quick examples. Warning cries have evolved in many contexts to warn others of danger. But they can be used in new and deceitful contexts. For example you can give a warning cry in order to grab an item of food from another individual. The individual's startled and runs for cover, you grab the food. You can give a warning cry when your offspring are at each other's throats—they run to cover and then you separate them and protect them from each other. It has even been described that you can give a warning call when you see your mate near a prospective lover—get them dashing to safety, and then you intervene.

In this continually co-evolving struggle regarding truth and falsehood, if you will, there are situations in other creatures as well as ourselves where we have to make tight evaluations of each others' motive in an aggressive encounter. I'm lining up against Marc Hauser; how confident is he of himself? I'm courting someone; the woman is looking at me; how confident am I of myself? And so on. That allows misrepresentation of these kinds of psychological variables and you can see how self-deception can start coming in. Be more confident than you have grounds to be confident and be unconscious of that bias, the better to manipulate others.

Once you have language, that greatly increases the opportunity for both deception and self-deception. We spend a lot of time with each other pushing various theories of reality, which are often biased towards our own interests but sold as being generally useful and true.

Let me just mention a little bit of evidence—and of course there's a huge amount of evidence regarding self-deception, from everyday life, from study of politics and history, autobiography, et cetera. But I just want to talk about some of the scientific evidence in psychology. There's a whole branch of social psychology that's devoted to our tendencies for self-inflation. If you ask students how many of them think they're in the top half of the class in terms of leadership ability, 80 percent say they are. But if you turn to their professors and ask them how many think they're in the top half of their profession, 94 percent say they are.

And people are often unconscious of some of the mechanisms that naturally occur in them in a biased way. For example, if I do something that is beneficial to you or to others, I will use the active voice: I did this, I did that, then benefits rained down on you. But if I did something that harmed others, I unconsciously switch to a passive voice: this happened, then that happened, then unfortunately you suffered these costs. One example I always loved was a man in San Francisco who ran into a telephone pole with his car, and he described it to the police as, "the pole was approaching my car, I attempted to swerve out of the way, when it struck me".

Let me give you another, the way in which group membership can entrain language-usages that are self-deceptive. You can divide people into in-groups or out-groups, or use naturally occurring in-groups and out-groups, and if someone's a member of your in-group and they do something nice, you give a general description of it—"he's a generous person". If they do something negative, you state a particular fact: "in this case he misled me", or something like that. But it's exactly the other way around for an out-group member. If an out-group member does something nice, you give a specific description of it: "she gave me directions to where I wanted to go". But if she does something negative, you say, "she's a selfish person". So these kinds of manipulations of reality are occurring largely unconsciously, in a way that's perhaps similar to what Marc Hauser in his talk was saying about morality.

A new world of the neurophysiology of deceit and self-deception is emerging. For example, it has been shown that consciously directed forgetting can produce results a month later and they are achieved by a particular area of the prefrontal cortex (normally associated with initiating motor responses or overcoming cognitive obstacles) suppressing activity in the hippocomapus, the brain region in which memories are stored. So there is clear evidence that one part of the brain has been co-opted in evolution to serve the function of personal information suppression within self.

What I want to turn to very briefly is the relationship between self-deception and war. Now war, in the sense of battles between large numbers of soldiers, is an evolutionarily very recent phenomenon. A raid, where you run over to another group, kill off a number of individuals, and run back, is something we share with chimpanzees. And that has a long history and is much more likely to be constrained by rational considerations.

But warfare as we experience it now is a ten thousand, (plus or minus a few thousand) year old phenomenon. Not an awful lot of time for selection. And not much selection necessarily on those who start the wars. There may be a lot of selection in the civilian population or the soldiers, but it's not necessarily true that those who start stupid wars end up with as as great a decrease in surviving offspring (and other kin) as one would have wished.

Wars also tempt us easily to self-deception for other reasons. There is often very little overlap in self-interest between your group and another group, in contrast to activities within the group. There is also low feedback from members of an outside group. There's greater ignorance.

And so war is a particular situation where self-deception is expected to be both especially prominent and especially harmful in its general effects.

Let us use the most recent war—the current war launched by my own country, the United States in 2003 against the country of Iraq—to see one simple illustration of how deceit and self-deception is a useful concept in thinking about war. It has been said that the first casualty of war is the truth, but we know regarding the Iraq war that the truth was dead long before this war started. We know the thing was conceived and promulgated based on a lie. The predator, the U.S., saw an opportunity to leap on a prey, and decided almost immediately, within days of 9/11, and certainly within a couple of months, to prepare and launch this war.

Now what's the significance of that fact? Well, one significance of it is, psychologists have shown, very nicely I think, for 20 years now, that when we are considering an option—whether to marry Susan, or to go to the University of Bologna instead of Barcelona, or whatnot—we are much more rational, we weigh options, and we are even, if anything, slightly depressed. But once we decide which way to go, we act as if we want all the cells in our body rowing in the same direction. If it's Susan we're going to marry, we don't want to hear about Maria or some of Susan's less desirable side. If it's Barcelona we're going to, that's the best university to go to and to hell with Bologna.

Now the point about this war is that there was no period of rational discussion of the pluses and minuses. The United States decided—at least a small cabal within it, including the President, decided—to go to war almost instantaneously. They immediately went into the implementation stage—your mood goes up, you downplay the negatives—after all, you have made your decision—and you do not wish to hear contrary opinions. Especially you do not wish to hear contrary opinions if the real reasons for going to war can not be revealed and the whole public pretense is a lie.

Thus, all planning for the aftermath was dismissed because it greatly increased the apparent expense and difficulty and suggested greatly diminished gains from the endeavor. This, of course, implicitly called into question the entire enterprise, so rational planning was dismissed. And witness the dread effects, a continuing bloodbath unleashed on an innocent population.

One other comment: self-deception can not only get you into disastrous situations, but then it gives you a second reward and that is, it deprives you of the ability to deal with the disaster once it's in front of you. And what could be more dramatic than what happened in the first month after the U.S. arrived in Baghdad—the complete looting of the country, 20 billion dollars of resources destroyed, priceless cultural heritage destroyed—all of that and the U.S. sat around and sucked its thumb. Did nothing to deal with it. And has been dealing with an escalating disaster ever since. A blood-letting of dreadful proportions, and still blind about what to do.

Well, I'll just summarize these thoughts by saying that there's good news and there's bad news. The good news is, we do have it in our grasp at last to develop a scientific theory of deceit and self-deception, integrating all kinds of information, but at least sticking this phenomenon out in front of ourselves and studying it objectively. The bad new is that the forces we're dealing with—that is, of deceit and self-deception—are very powerful.

ROBERT TRIVERS' scientific work has concentrated on two areas, social theory based on natural selection and the biology of selfish genetic elements. He is the author of Social Evolution, Natural Selection and Social Theory: Selected Papers of Robert Trivers; and coauthor (with Austin Burt) of Genes in Conflict: The Biology of Selfish Genetic Elements. He was cited in a special Time issue as one of the 100 greatest thinkers and scientists of the 20th Century.

Robert Trivers's Edge Bio Page

...there is a deep relation between Einstein's notion that everything is just a network of relations and Darwin's notion because what is an ecological community but a network of individuals and species in relationship which evolve? There's no need in the modern way of talking about biology for any absolute concepts for any things that were always true and will always be true.

LEE SMOLIN: COSMOLOGICAL EVOLUTION

(LEE SMOLIN:) I'm a theoretical physicist, and I'm here to talk about natural selection and Darwin. The main thing that I'll have to communicate is why somebody who thinks about what the laws of nature are has something to say about Darwin and the impact and the role of Darwin in our contemporary thinking over all fields.

But as a way of getting into that, I want to say something—and you're going to hate me for this—about John. When John talks about the Third Culture, what he has done, besides create the idea, is create a group of people. I don't know if it's a community, there are very close friendships in it, many of which—in my case they are with people whom I met through John. This conversation that he talks about is a real conversation, which, at least as far as I know, was not happening and would not be happening were it not for John.

I think it is not so usual that John appears with the people whom he talks about and writes about and it is wonderful to be here with him. So I wanted to say ‘thank you' publicly because when I started to think about Darwinism, I didn't know any biologists and I didn't know any psychologists—the academic world is very narrow—and I didn't know any artists or digerati. It is because of this involvement that I met many of the people I admired and whose work has inspired me.

I think it is not so usual that John appears with the people whom he talks about and writes about and it is wonderful to be here with him. So I wanted to say ‘thank you' publicly because when I started to think about Darwinism, I didn't know any biologists and I didn't know any psychologists—the academic world is very narrow—and I didn't know any artists or digerati. It is because of this involvement that I met many of the people I admired and whose work has inspired me.

Now I want to make a claim and my claim is that while Darwin's ideas are certainly completely absorbed and verified within biology, the whole impact of Darwin's ideas is as still yet to be absorbed and felt and the impact is going to happen in my field of theoretical physics and cosmology and I see it happening in other fields –mathematics, social fields, and so forth. Also I want to make a hypothesis about why—and I'll speak about my field because I don't have any rights to speak about another field, but I think the resonances and the similarities are there.

In my field, two things happened in the 20th century that we're absorbing. One of them is Einstein and the revolution of physics started by Einstein, both relativity theory and quantum theory. And I'm going to claim in my brief time—I'm not going to have time to fully justify—that the main development and the main meaning of Einstein's contribution is closely related to the main meaning of Darwin's contribution. At least I'll say why in a few minutes.